We Got Our Own: Creating ARTS.BLACK

Jessica Lynne talks about making a home for black art critics online.

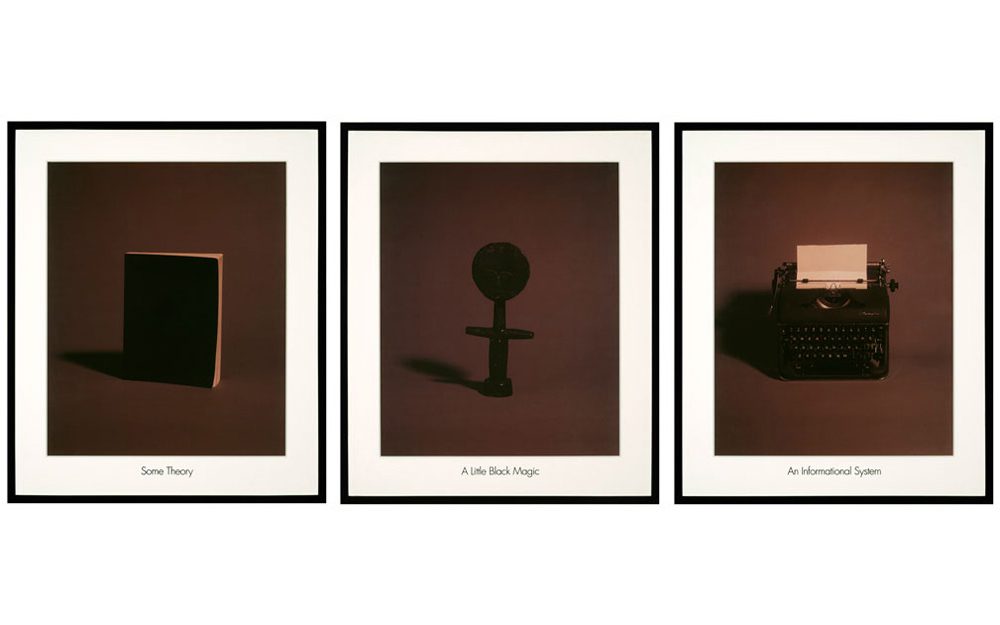

Three images selected from Carrie Mae Weems’ installation And 22 Million Very Tired and Very Angry People, 1989-1990. Courtesy carriemaeweems.net.

During the second semester of my freshman year in college, I enrolled in an art criticism course. My motivation? Nothing more than the fact that I had taken a course with the professor the previous semester and a casual compliment from my homegirl Ash: “I think you’d ace this class.” Ash and I clicked as soon as we met and quickly made a pact, as writers, to pursue similar paths as we matriculated. This art criticism course taught by a professor we both deeply admired seemed like the next natural step on our joint paths towards literary greatness.

I had not a single idea what the hell art criticism was. And if it was anything like journalism, I told myself, it was a dark void where failed fiction writers went to publish as a last resort. Nevertheless, I enrolled. There I was: eighteen and wide-eyed, trying to figure out how to correctly pronounce the name Wayne Koestenbaum.

The syllabus intimidated me. There was Koestenbaum, of course, and Susan Sontag, Dave Hickey and just so many essays on Warhol. Ash and I soldiered through, not quite sure what to make of the newfound world of theory but steadfast in our commitment to our budding craft and the professor who was slowly but surely opening our eyes. She was the same professor who had introduced us to James Baldwin after all. By month three, our twice weekly classes had become a safe haven of sorts. A collegiate refuge where I could unpack this no longer strange thing: the art critic.

The thought had not yet occurred to me that this thing—the art critic—was an existence that I could one day hope to assume (does anyone ever really aspire to become an art critic?). This thinking was certainly rooted in the harsh economic realities of a professional writing career. And a flip through any newspaper or art magazine revealed there were many levels to this game. How much more would this aspiration be complicated by my marked identity as both black and woman? Where were all the black art critics?

Then, I found bell hooks.

Initially, I approached hooks’ work with some distance. I had read a few of her essays and was easing my way into black feminist theory but had yet to truly secure my academic footing in regards to such theory. Still, as the only black woman enrolled in the course, I felt a responsibility to hooks—to not let her down as I sat in a room among my many non-black peers engaging with her words. I was finding a language as a black woman and feminist and it was as if hooks herself had added a third category: black, feminist, critic.

And so I devoured the assigned reading, Art on My Mind: Visual Politics, like no other book I had ever read. If you know hooks, you know that her prose is gut-wrenching, honest, and immediately impactful. She was all the affirmation I needed. You, yes, you can be an art critic, Jessica.

But I’m stubborn.

Instead, I fled to haiku poetry and young-adult fiction and (in hindsight) some bad hip-hop writing before making my way back to art criticism. Quite frankly, I lacked the confidence and motivation to take myself seriously. How would I start? What would I write about? Does this mean I’m officially a failed fiction writer? Where would I publish?

And then I returned to bell hooks.

I would not consider myself the most internet savvy person (blasphemy for a millennial but it’s true). I still get annoyed by Facebook; I just joined Twitter last year; my plans for a personal website still have not materialized.

So when another homegirl, my now ARTS.BLACK co-editor, put the entire world on blast it seems by asking on Facebook, “Where are all the black art critics?” I secretly cringed because I knew she was coming after me. It went like this via text message:

Tay: “I’m talking ’bout YOU”

Me: “I CANNOT DO THIS”

Tay: “YES YOU CAN. YES WE CAN.”

Taylor had already purchased a domain name, ARTS.BLACK. “If we can’t name five black art critics—writers who are actively publishing and writing about art—why don’t we give them a space,” Taylor opined. “If we are really serious about striving for equity in the art world, now is our chance,” she said. “To the internet be the glory!”

Don’t get me wrong. I love the internet even if I’m not its most skilled navigator. I was co-editor of another small online publication for almost five years. However, this time the task seemed too daunting, too enormous. Would anyone listen to us? Taylor’s text message:

Tay: “We’ll make them listen.”

There was bell waving and screaming her hands. You, yes, you can be an art critic, Jessica.

ARTS.BLACK is a platform for art criticism from black perspectives. It is a digital publication. It is a website. It is a public space that we built.

It is not lost on me the ways in which black folks are rendered hypervisible and hyper-vulnerable in the age of the internet—the digital public. We know that the internet can replicate and become an extension of the same apparatuses of violence and trauma that have harmed black people for years. We know that black intellectual and creative labor is consistently unvalued and undervalued. We know that digital sharecropping—a term coined by author and scholar Renina Jarmon to indicate the ways in which the capital of marginalized people is harvested and exploited online—is real. And thus we know that ARTS.BLACK does not immediately mean a shift in the power structures that govern the white cube.

But I return to bell hooks.

We make no money from the ARTS.BLACK website and we can’t pay our writers. I ask myself: How do we ensure that we aren’t participating in the same processes that dismiss and devalue black labor? What is the business model that makes most sense for this work in order to support the community we are hoping to cultivate?

We have been the generous recipients of support and encouragement from so many colleagues in the field who have positioned themselves as allies and friends. We have also found ourselves the objects of stark criticism from individuals who question whether the decision to only publish black writers further widens an undebatable publishing chasm. If we can’t pay writers in an industry that already pays peanuts, how exactly can ARTS.BLACK purport to offer solutions?

We do not have all the answers. Still, I know that this digital space matters. I know that this public space matters. I locate ARTS.BLACK in a lineage of black creatives who have used the collective as both a site of resistance and shelter. I romantically imagine ARTS.BLACK becoming a modern-day, digital version of Fire!!, the short-lived literary and artistic magazine of the Harlem Renaissance.

It is important for black critics to know that there is a home for them. Despite the unanswered questions, the second guessing, and the fluctuating levels of exhaustion, the sustaining of this home matters. That this home lives online is a deliberate decision—an attempt at an intervention.