Monuments of Acknowledging

Amy Mackie discusses alternative, artist-driven strategies within the debate to remove controversial monuments in New Orleans.

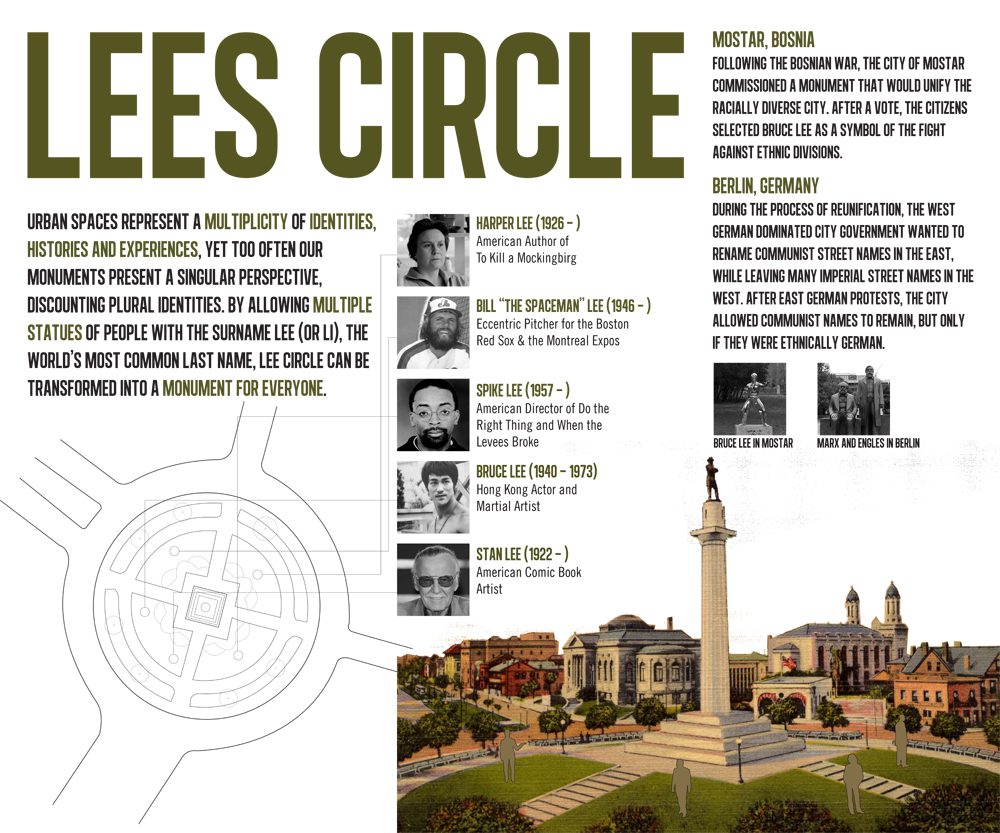

Zakcq Lockrem, Lees Circle, 2011. Proposal. Courtesy the artist.

“Our Public Space – A Public Discussion,” is a public Facebook group initiated on July 20, 2015 by New Orleans-based artists and educators Courtney Egan and Anne Gisleson. Since its creation, it has served as a space for dialogue and information sharing, prompted in part by the recommendation by the New Orleans Historic District Landmarks Commission in tandem with the city’s Mayor’s Office for the City Council to remove four Confederate monuments in New Orleans. Though there are civic reminders of the Civil War and the city’s Confederate history in nearly every neighborhood in New Orleans, the four monuments that have been the focus of this controversy are the Robert E. Lee monument at Lee Circle, the equestrian statue of P.G.T. Beauregard at the entrance to City Park, the Jefferson Davis monument in Mid-City, and the Liberty Place monument in the French Quarter.

The Facebook group has become a productive space for questions, but of particular importance are the following inquiries: Why these four specific monuments? What will take their place (a plaque, a new public commission, a void)? Where will the monuments be relocated if anywhere? How much will it cost and why isn’t the money being spent to address the city’s most pressing issues (e.g. crime, poverty, affordable housing)? And will this lead to other actions regarding monuments or streets named after military or political leaders, modified language to talk about these histories, or updated textbooks in our schools to reflect their revisions? Perhaps, in opening up this dialogue, these monuments can pave the way for us to reconsider the way our nation’s history is relayed and remembered on multiple levels.

The City Planning Commission has made archived videos from public hearings on the subject available online, which represent differing responses and perspectives about racial politics and revisionist histories. These constitute one component of a 60-day period for public comment that concluded on September 7. However, as Gisleson has accurately pointed out, the city doesn’t have the best track record in respecting public comment. And in much of the online chatter (and in public gatherings), opinions are very divided and often hostile. Take ’Em Down NOLA and Monumental Task Committee, Inc., for example, represent two local groups with diametrically opposed opinions on this issue. In working through my own feelings on the subject, I have found it useful to look to the ways artists and activists have found creative approaches in bringing attention to the complicated subject of public monuments in other contexts.

According to Egan, the Facebook group was inspired by the group exhibition, “monu_MENTAL” at Antenna Gallery in 2012 through which she invited artists to reimagine existing nineteenth and twentieth century New Orleans monuments. Before it was a hot-button issue in the news, the exhibition included reimagined versions of the Robert E. Lee and Jefferson Davis monuments amongst others. Some of the proposals/renderings called for the removal of monuments, but others involved additions as in the case of Zakcq Lockrem’s proposal to add complementary statues of Harper Lee, Stan Lee, Bruce Lee, and Spike Lee alongside General Lee, thus creating a more egalitarian (and more ethnically diverse) Lee Circle. In the words of Lockrem, “Urban spaces represent a multiplicity of identities, histories, and experiences, yet too often our monuments present a singular perspective, discounting plural identities. By allowing multiple statues of people with the surname Lee (or Li), the world’s most common last name, Lee Circle can be transformed into a monument for everyone.”

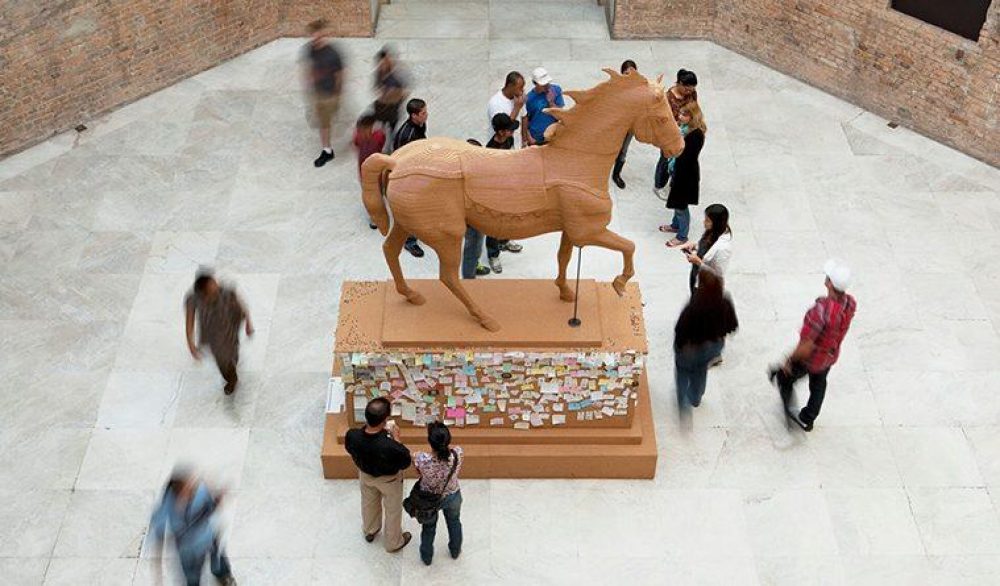

PAUL RAMÍREZ JONAS, THE COMMONS, 2011. CORK, PUSHPINS, AND NOTES CONTRIBUTED BY THE PUBLIC. COURTESY THE ARTIST.

For the last decade or so, New York-based artist Paul Ramírez Jonas has considered the way his sculptures, performative lectures, and installations can encourage public debate about the roles monuments play in our cities. Most specifically, in The Commons, 2011, he created a replica of a ten-and-a-half-foot-tall statue of a military horse minus the rider made entirely out of cork. At the base of the sculpture he provided pushpins and Post-it notes, and the public was invited to interact with the piece by contributing a slogan, creed, or other words of wisdom. This invitation reiterates that monuments exist in communal spaces, thus they are always about a relationship to the public. Ramírez Jonas describes The Commons as follows: “This is a monument, unusual in that it has no rider, unusual in that it implies the viewer. I use cork, because it is a material that can publish an endless number of voices, our voices. It opposes the singular voice of the State, or the singular identity of the ruler or hero normally portrayed on a horse, or the singular, immutable inscription on the public space that bronze and stone allow.” Ramírez Jonas’ approach to monuments provides an interesting counterpoint to the monuments currently being evaluated in New Orleans, in suggesting that the relationship they have to the public can be encouraged as forever fluid.

Another New York-based artist, Andrea Geyer, unveiled a series of events and public programs in 2004 designed to draw attention to Audrey Munson, the woman who served as the model for more than 15 statues in New York City. The impetus for this project was in part that Munson had been effectively rendered invisible, calling attention to all that is unseen and unconsidered when we boil complicated histories down to singular emblems. People move past monuments, sculptures, and statues unknowingly in public spaces every day, and often they have no idea who these historical figures are, why there are monuments erected to remember them, or how there might be a connection between history and their everyday lives. With the debate as it currently stands in New Orleans, it seems important to acknowledge that there is plenty to be gained for the politicians arguing both for and against these monuments’ removal. For academics and historians, there is also much to be lost in terms of educating people about this country’s ongoing relationship to its slave-driven history.

As part of the growing archive of articles, information, and discussions on “Our Public Space – A Public Discussion,” Gisleson posted an article in August that focuses on a situation involving a contemporary artist and a historical monument in Indianapolis, Indiana of a freed black slave. Artist Fred Wilson, who is well known for bringing to light overlooked histories of the African diaspora, submitted a proposal for a project entitled E Pluribus Unum that became the center of a controversy in the city. Wilson’s proposal was rejected primarily because community members did not want the city to draw attention to or replicate a sculpture that depicts a negative black image, regardless of its grounding in history or the intentions of the artist to expose that history’s very real connection to the present.

I later posted a link to In Step With the Time (2012), a film by Anton Partalev, which documents an action by a group of artists and activists in 2011 in Sofia, Bulgaria. During the night, the group painted the Soviet soldiers portrayed in the Monument to the Soviet Army (built in 1954) as American “superheroes” accompanied by the slogan “W zgodzie z duchem czasów” (in step with the time). In Partalev’s brief documentary, the artists explain that they wanted to draw attention to the fact that Bulgaria is still under the influence of Russia and is haunted by its Socialist past. This monument has been painted numerous times since (for various political reasons) and in 2012 was the site of a Pussy Riot protest. This monument from the post-Soviet era and the debates for and against its removal are clearly motivated by much different agendas than those we are currently witnessing in New Orleans, but they force similar questions about how we remember and memorialize the tragedies of our past and think about the possibilities for the future.

As Egan mentioned on “Our Public Space – A Public Discussion,” the Fourth Plinth Project in London’s Trafalgar Square represents yet another creative approach to the installation of and/or response to the presence or absence of monuments. Since 1999, artists have been commissioned to respond to an empty plinth in a busy city intersection, which has lead to a host of political and thought-provoking interventions by contemporary artists. Projects such as the Fourth Plinth might serve as inspiration for the future of monuments in New Orleans, where changes, additions, and multiple voices become part of the life of the monument.

Consider the “Black Lives Matter” tag that briefly appeared on the P.G.T. Beauregard monument in City Park. While some saw that particular addition as defacement, the idea that adding more human contact provides another layer of meaning/understanding is really appealing to me. If we (as a city, state, nation) are going to begin to properly address our racist, violent, and divisive past we need to contemplate everything from other monuments that embrace discrimination of any kind to the way history is portrayed in textbooks. Dialogue and open networks of information sharing through initiatives such as “Our Public Space – A Public Discussion” will hopefully inspire new ways to talk about where we have come from and where we want to go, so that we might build monuments (or modify, or remove existing monuments) and create public spaces that more accurately represent our complicated world.