Tactile Fixation: An Interview with Aubrey Longley-Cook

Laurence Ross speaks with Atlanta-based artist and "(De)Tangled" contributor, Aubrey Longley-Cook, about humor, drag, and stitching.

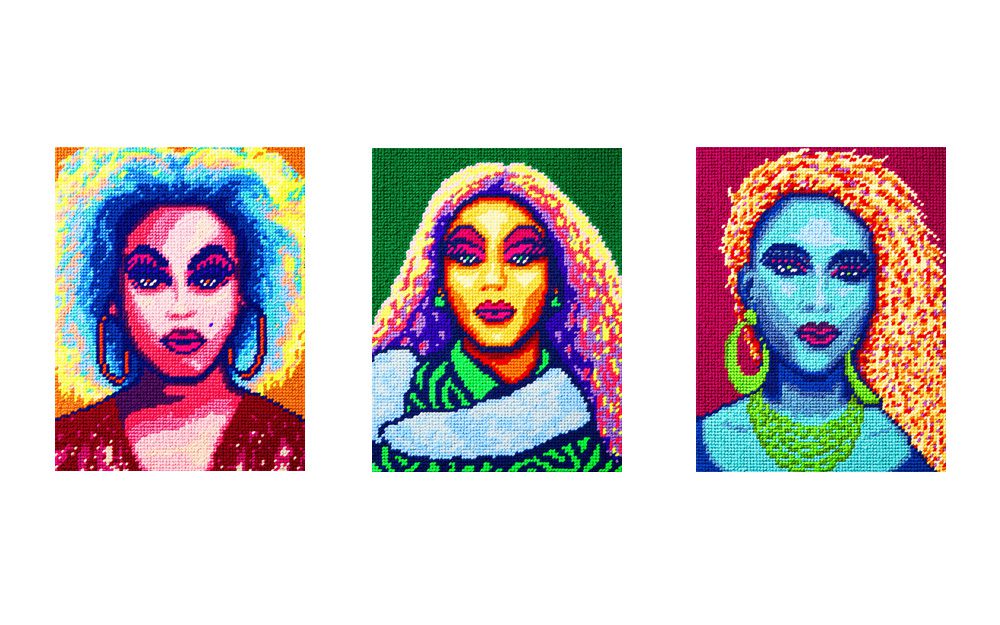

Aubrey Longley-Cook, Cayenne Rouge, Brigitte Bidet, and Ellisorous Rex (From Left to Right), All 2013. All Needlepoint. Courtesy the artist.

Laurence Ross: Why did you begin with—and why have you stuck with—embroidery as a medium for your work?

Aubrey Longley-Cook: I started doing embroidery work when I was about nineteen. I was in art school at the time and I was drawn to it because embroidery has this real tactile sense. I was studying animation and in my free time I would hang out with friends. I needed to work on something even when I was just hanging out. I kind of have—what’s that called when you need to have something in your hands? It’s not oral fixation…

LR: Tactile fixation?

ALC: Yeah, I like that. I guess I was inspired by a couple of things. I noticed a trend of fiber work coming back—some album art that I really liked at the time. There was Joanna Newsom’s The Milk-Eyed Mender, a beautiful collage-like embroidered cover, and this Caribou album that had this nice, kind-of-quilted front. My mother had done needlepoint when she was pregnant with me and my siblings, and I had one of her samplers right above my bed at that same time. I kept it above my bed for years. I’ve since passed it on to one of my nephews, just to keep it in the family.

I’m not sure why, but one day I picked up a needle and thread. I started working on canvas. I painted the canvas and stitched into it. I tried collaging, putting objects onto canvas, stitching them on, stitching around them. Quickly, it just became about the stitch work. Eventually, I moved into fabric and tried stitching into paper or found books, really exploring it. It was purely for me. I did it outside of school for two years, and then my junior year I was able to take a fine art textiles class at RISD (Rhode Island School of Design). It was free and open, so I was able to do my own thing and work with other textiles students, all while continuing my animation work.

While I was in school, I separated animation from embroidery. One was my studies, what I was working toward, more of a career. The other was this personal stuff that I really enjoyed. It wasn’t until I came down to Atlanta that they started to intermingle and play together. That’s when it got exciting. At first, it seemed impossible to combine them. They are both so time-consuming. Once I was able to figure out that I could do a small animation loop and design something that can repeat—a set of between nine and forty frames—it became much more doable. With the emergence of GIF culture, there is a new audience and a new format for sharing work that is very short by animation standards. For years, animators were plagued by this idea that you could do an animated short, but to sell your work you needed to make feature films. People were working and working to create these massive things. That’s why independent animation is so tricky. It’s just so time-consuming for one person to take on.

LR: The pieces of yours that I’ve seen remind me of flip books that, at least when I was a kid, seemed ubiquitous. Thirty, forty, or fifty page books that you quickly flipped through. Not much more than a gesture happens.

ALC: I think that’s a good reference. Or a zoetrope, those circular animations that would loop before film projections even existed. People were creating these toys with looping movements.

LR: This leads me to a question I wasn’t anticipating. How would you describe your work in terms of play?

ALC: I like leaving room for humor in my work—a piece that makes me chuckle when I’m working on it. It’s part of my personality to have a little bit of laughter in there and introduce the serious at the same time. I think it’s a good way to work with emotions and pull people in. It also plays off of that kitsch factor. A lot of embroidery, especially American embroidery, has this history of the mass-produced sampler, part of the 1970s revival arts and crafts movement. Much of that stuff has these goofy sayings or phrases, jokes, or puns. I like to reference those kitsch embroideries, while also suggesting the joke has a more serious undertone or something more subversive that it’s trying to say.

My work is labor intensive and projects can take months, so the element of playfulness also helps me to stay engaged and not become overwhelmed. I think everyone appreciates a little fun, right?

LR: Yes. What do you think the effect is, for you, of work that is simultaneously serious and a joke?

ALC: It reminds me of David Sedaris talking about his writing, how he will go from this very serious phrase to a joke, back and forth from laughing to crying. I don’t know if that’s specific to queer artists or queer work, but I think that creating work that is in this liminal space leaves room for ambiguity and makes the work open to interpretation. Often I am playing with themes that are more serious than most of my audience will pick up on, whether it is referencing personal stuff that I’m going through or a larger queer narrative or identity. Those undertones are important to me.

LR: A lot of Camp scholars describe work that is “Camp” as work that takes itself seriously but comes off as a joke. It’s a serious joke, but many people miss the joke. It seems like your work may be the inverse of that, where people are seeing the playful side of it without seeing the serious side of it.

ALC: I think that may be the case, and it fits with my personality. On the outside, I am very open and out there, friendly and talkative. But I am also a total introvert. At the end of the day, I’m shut off in my own space and need that time to come back. There is a serious core underneath all of those jokes and flamboyance. That’s something to think about.

LR: I wonder what people would call that aesthetic. I wonder if there’s a name for that aesthetic.

ALC: I don’t know what I would call it, but I like that it has that inverse effect. I do appreciate Camp, but a lot of times I feel my work is slightly different than that—maybe that’s what that slight difference is. I’m inspired by Camp. I think it’s funny, and I think there is a certain degree of Camp in my work, or a certain degree of kitsch. But again, I feel like I’m in on the joke and I invite the audience to be in on the joke too. Or the inverse of that, not in on the joke, but in on the statement, in on the serious.

Aubrey Longley-Cook, Runaway Back View and Runaway front view, Both 2010. Both Embroidered Animation. Courtesy the artist.

LR: Well, your work does literally have two sides.

ALC: Right. Exactly! I mean, with the Runaway piece, which is this looping animation of my roommate’s now-deceased dog, who was a stray dog that he found and lived with for four years, I created that portrait while the dog was still alive and that piece was two sides, this duality. The front side being his life with us, a happy wonderful relationship; the backside, that chaos, that unknown past. With an animal, you can’t ask what happened, why he was on the street, what he was doing all those years before he was found. That dog had a lot of psychological issues. Any loud noises would set him off and he would go crazy. If there were gunshots in the neighborhood, or fireworks, or a thunderstorm, he would go bonkers. He would bust through a screen and run off. I always thought about the backside, where you get all the knots and ties, what you are subconsciously creating by making the front side.

LR: Which would be particularly poignant when you are doing portraits, busts, or heads.

ALC: Certainly. With the Lavonia and RuPaul pieces, even more so. I was hesitant with the drag work to highlight the two sides and duality because I didn’t want people to interpret it as duality of gender. I didn’t want to seem as if I was saying “this is the male side and this is the female side.” It’s really not about that. Maybe masculinity and femininity is a better way to put that—on that spectrum.

LR: Or even the simpler concept that one is the façade that people typically see and the other is what’s underneath the façade. They are both real, just as both sides of the embroidery are real—just different perspectives on that same subject/object.

ALC: Yes, and sometimes both sides are visible at the same time or it shifts back and forth right in front of you. Last night I was at a drag pageant for Miss Glitz and Lavonia Elberton was hosting it. They crowned this queen after six weeks of ten contestants. At Mary’s, there is more of a subversive drag scene than at some of the other pageants in Atlanta. I’m a part of the drag scene here. I really appreciate it and I wanted to pay homage to what’s going on right now in this city and put a spotlight on that. A lot of people are talking about the resurgence of drag internationally and I’m certainly not the only person picking up on that or spotlighting it. But again, I think it’s important to talk about local talent and to document local scenes. Drag queens are reaching this celebrity status nationally, mostly through RuPaul's Drag Race. I think it is equally important, if not more important, to talk about the dynamics of a local scene.

LR: And is that why you chose Lavonia as one of your subjects?

ALC: It is. Lavonia was actually the owner of the dog, Gus, from the Runaway piece, and he’s been my roommate for going on eight years. Lavonia’s a drag queen, yoga teacher, poet, artist, lots of stuff. We’ve collaborated. We had a two-person show in 2010. We go back and forth on ideas and help each other. Certainly he/she has a presence in my work. And I wanted to convey that intimacy. With the RuPaul piece, I had zero permission to use images of her face or the footage. I abstracted the footage in a way that hopefully… I’ve never heard from any lawyers. But to balance RuPaul, I wanted to have this work that was very of the now for Atlanta and also of people that I am directly associated with, who I know, and who I see perform. In Lavonia’s performances, many times, whether it’s holding a giant puppet, working the fan to create wind, putting hot water on dry ice, or doing sound cues, she’s put me to work. It’s that intimacy and it’s that immediate connection.

I picked RuPaul for a subject because it was a group-sourced project. I wanted to create a project where the person that people were stitching would be known to anyone, even strangers, and then those people could be excited to create the portrait. At the time, I was already doing the other drag portraits and a friend of mine reached out to me about starting a workshop. Maggie Ginestra and I created this project together and once people heard about it, they wanted to be a part of it. They wanted to offer space or assistance in some way. Normally my work is pretty insular, just me working day and night. So to go from that to a project that encompasses a huge number of people, I became more of a project manager. It was obvious that I hit a nerve, right? I could tell that this work was important because everyone wanted to be a part of it. That was really a treat of a project.

I’ve been developing proposals and looking into other ways to continue that type of process. That project took nine months, and it was a lot of work. I definitely needed to take a break from the project management aspect and focus on my personal stuff for a minute, but I am open to it again. I am just starting a new series of portraits of queer people in Atlanta that inspire me. I am starting with the playwright Topher Payne. He wrote this play called Angry Fags that is genius. This project is just me working. It might be another year—or two or three—before it actually comes together, but at least the ball is rolling.

LR: Do you think there is an aspect of the medium in which you work that is queer itself? Do you think that your medium lends itself to your subject matter? Or is it too intertwined to say?

ALC: Yes and no is my answer. That’s a tricky question because it falls into that idea that anything that’s fiber or textile-related is inherently woman’s work, which I think is incorrect. There have been sailors, farmers, military men, and others throughout the ages who have done embroidery and fiber work. From our modern viewpoint, at least in America, we have that vision of the ’70s housewife who is working on a needlepoint, and I get that. I have played off of those queer undertones, of a man doing embroidery, especially a man who is six-foot-seven.

I fly for photo shoots and I’ll take embroideries with me. I’ll work in the airport or on the plane. I love that stitching has this almost performative aspect because people will come up to me and they will freak the fuck out. “Oh my God! Oh what are you working on?” Flight attendants especially. I think when I first started, there was a little shock value that came with it and that got people excited. They would talk to me about it and that’s great, right? When you are working on something, you want people to be interested and excited, but for me now going on a decade of doing this type of work, it’s grown beyond that. They are just the materials I use, and I wouldn’t say that animation is a queer art form. Sure, you could make arguments that anything is a queer art form if you put the right stuff behind it, but it’s really just the hands and the mind behind it. I am certainly putting a lot of queer theory and subversive stuff into my work and a lot of my imagery and subject matter plays with that more than the technique itself.

Aubrey Longley-Cook, Lavonia Elberton Front View, 2013. Embroidered Animation. Courtesy the artist.

Aubrey Longley-Cook, Lavonia Elberton Back View, 2013. Embroidered Animation. Courtesy the artist.

LR: It’s interesting to hear you say that you view doing your work in public as a performance. You used the word “performance.” Since some of your subjects are performers, your performances sometimes reference other performances.

ALC: Right, and I love that. I don’t think that I initially felt that way about it, but very quickly I realized that it is something unique to do in public. One woman on a plane just last month literally climbed over the seat to talk to me. I had my headphones on and I was working and she tapped the shoulder of the woman next to me—who had a baby in her lap—just to get my attention. I see people watching me, and I’ve noticed that it has this performative quality that I like.

I also like what you are saying about my performance documenting another performance, because when people talk to me about it, I'm quick to talk about the subject matter. “Oh I am working on this portrait of so-and-so, and they are an Atlanta drag queen or an Atlanta playwright.” It quickly becomes a sharing moment when I am able to talk about this person who inspired me and pass on their name. I am into the idea of alternative documentation in the modern era, when everything is documented on cellphones, photography, or video. Historically, before all of these technologies were commonplace, things were documented through illustration or painting or textiles, which inherently abstracts the subject matter. It seems important that I am documenting people now, doing things now, and creating interesting work now, in a way that is different. I like taking on this documentation of community. That’s become an important part of my work, at least in the past few years.

I worked through a lot of stuff I just needed to do during my first five or six years of doing needlepoint. I did a show that was all about boyish fantasy, with castles and knights and dragons, and got that out of my system. A lot of stuff about death that I was working through because my mother passed away when I was fifteen from cancer. She was one of the big references and impulses to start needlepoint. Then I just got to this point where it didn’t need to be about me anymore. It became more important for me, almost in a curatorial way, to say: “these are people around me that I find important or inspiring or essential and they deserve this documentation that is clearly labor intensive and intimate.” With the Atlanta drag queens, it’s that idea of these underdogs. At the time that I started the Lavonia Elberton portrait, she had just started drag. She was basically unheard of. And now, she has really come into her own and made a name for herself. She’s even said that during the project—which is only nine frames and took a year and a half—there were a couple of times when she almost quit performing. But because I was doing that project, it kept her tied in and tethered to this persona and she kept seeing it through.

LR: This might be more closely related to what I was asking about earlier, rather than the idea of needlepoint or embroidery being necessarily feminine rather than masculine. Needlepoint does, at least culturally, reside in an area of domesticity and kitsch. You are literally taking it out of the home, putting it into airports and gallery spaces. Because of the technique and the time and the labor that’s involved in some of your projects, and the number of people involved, it reminds me of five or six people sitting around a table working on haute couture dresses.

ALC: Or an animation team. For most animations, there are rows and rows of animators working to create, like a knitting circle, a crew of people working on a giant tapestry. I think it does have that sense of domesticity, that reference to the home. I love that the materials are soft and clean. There is something so satisfying about that. I can take it anywhere. I have friends who paint, and if you are working in oils, you have to work in your studio. Maybe if you are a plein air painter, sure, you can make do. But I am really lucky that I can roll something up, put it in a tube, and go. That idea of taking it out of the home and into public spaces and galleries and really celebrating and elevating this work is important to me too.

For a while, I collected and thrifted vintage needlepoint stuff. A lot of times, it would be the work of an unknown artist. Maybe it was signed; maybe it wasn’t. I liked taking this work and putting it in new context, collecting it and having this collection that preserves the work and elevates it from simple craft to real artwork, because why not? I am often asked in interviews: “What do you feel about the difference between art and craft?” It’s such a common question and at this point it’s become such a frustrating one. I do maintain slight differences in the terminology and I am so used to answering the question. At the same time, people ask that question as if art and craft are opposite ends of a spectrum, but they’re not. It’s not like art or craft, one or the other.

LR: Your work, in a way, should annihilate that question. To me, that is the way in which your work is the most queer. You are taking an object and questioning or complicating its identity. The history of embroidery being a personal or domestic activity is not erased, but put in a very public space, and an art space. Taking something that is relatively lowbrow and putting it in a relatively highbrow space. It’s still the same object, but now there is a multidimensional aspect to it. That’s what I think is queer about your medium—not that fact that you are a man doing needlepoint or embroidery.

ALC: That’s interesting. And also the importance of the object as an artifact in the digital era, creating work that obviously comes from a real, physical, handcrafted thing. In this day and age, often we watch things that are so seamless that you have no idea how they are crafted. You look at a Pixar movie and they are designing programs specifically to create that movie, to create these characters and these movements that are flawless. One thing that I really enjoy about creating my work is it puts such a direct spotlight on the physicality of the work. I love showing the animations with the physical frames because I love seeing the light bulb go off in people’s heads when they realize this comes from this. Then there is the front and back of the fabric, when people realize that you can animate the backside of the fabric just like you can animate the front, and that the movement still registers. There is something really exciting about that. All through school I did sand animation, watercolor animation, all super traditional. I took one 3D animation class and one after-effects class, and while that stuff was interesting, it really wasn’t what inspired me. I’m such a tactile person that even if the final output is a digital file, at least it comes from this very physical place. I like to put my hands on things.