Due Process: The Legacy of Sylvia Roberts at Tulane University

Benjamin Morris discovers the archives of Louisiana lawyer Sylvia Roberts.

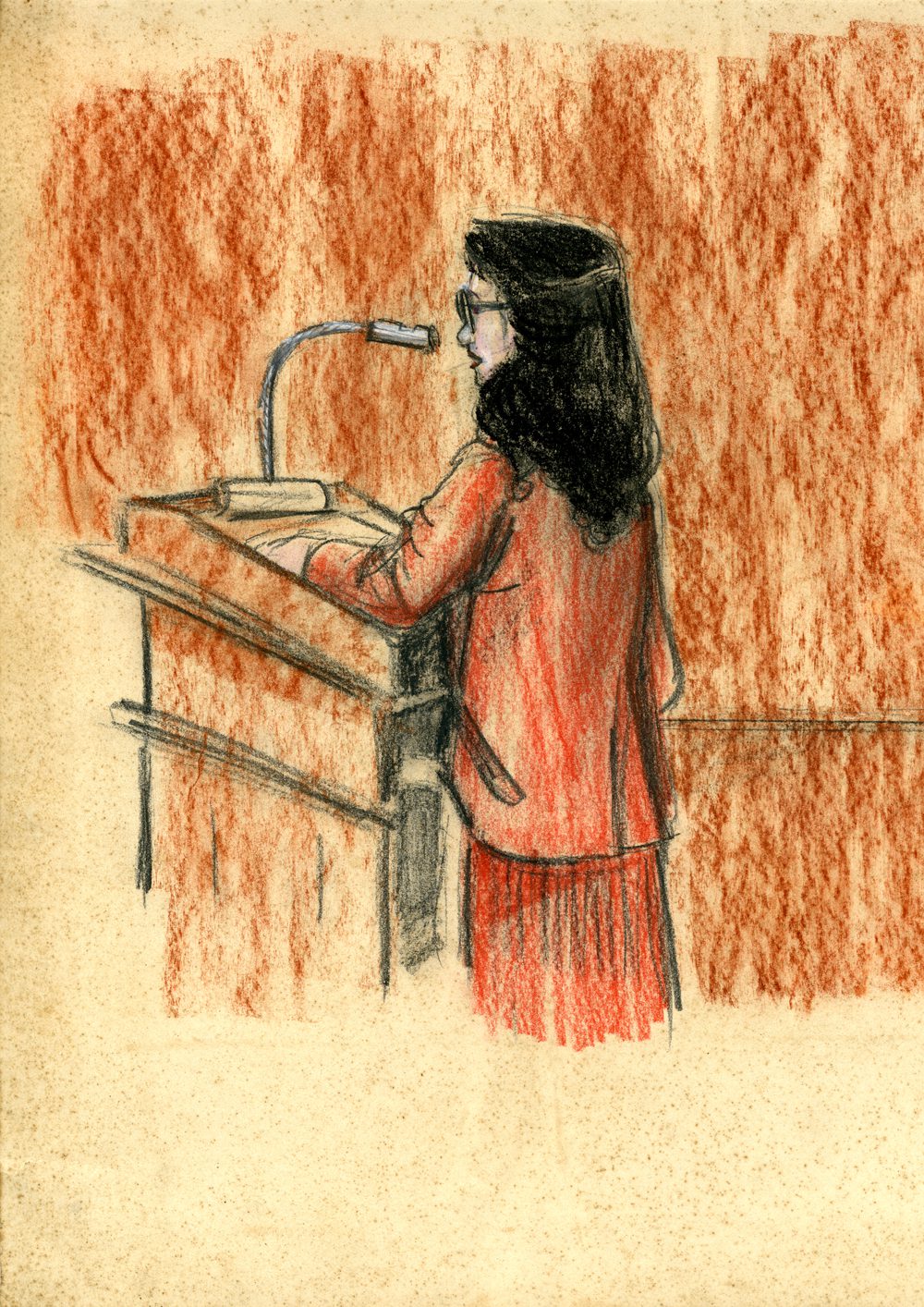

A courtroom sketch by an unknown artist from Sharon Johnson v. University of Pittsburgh (1973), part of the archives of Sylvia Roberts at Tulane University, New Orleans.

The sketch is medium-sized, done in charcoal and colored pencil in warm oranges, browns, and reds, a three-quarter profile from the rear. A woman in a suit stands at a podium before a judge, her words a mystery to those now observing her decades after the fact. Yet those words and the arguments they formed have impacted countless Americans—words by Sylvia Roberts (1933-2014), a Louisiana native and co-founder of the state chapter of the National Organization for Women (NOW), and one of Louisiana’s most prominent attorneys of the last century.

This sketch, the creator of which is unfortunately unknown, is one of the thousands of documents recently acquired by the Newcomb Archives at Tulane University, where Roberts earned her law degree in 1956. Perhaps most famous for her work in the case of Lorena Weeks v. Southern Bell (1969), a case that established the groundwork for much subsequent legislation protecting against gender-based workplace discrimination, Roberts’ long practice at the bar extended far beyond the high-profile cases for which she is known. She was one of the first presidents of NOW’s Legal Defense and Education Fund, serving from 1972 to 1974, and acting as general counsel until at least 1984.

According to Susan Tucker, former director of the Newcomb Archives, “Roberts knew her records were important—she knew exactly what she was doing in saving everything.” Praising Roberts’ personal humility in the pursuit of greater justice for others, Tucker added, “On a personal level, she worked against violence against women, and in her cases would often talk about ‘making a person whole again’ through the law. That kind of work was very intimate. But on a wider level, she was also working towards a better society—she knew she was changing the world.”

Following Roberts’ death last year, Newcomb archivists negotiated with her family and associates to acquire her material, which at the time measured 120 linear feet (a figure expected to shrink following processing and categorization). The collection spans the majority of Roberts’ life, from her undergraduate days at the University of California, Los Angeles to her later education at Louisiana State University, Tulane Law School, and the Sorbonne and includes her early case work in Baton Rouge before her major cases such as those she litigated for NOW in the 1960s and ’70s. All told, the papers comprise over 60 years of Roberts’ career.

While smaller collections about specific areas of her work are available at LSU, the University of Louisiana at Lafayette, and the Schlesinger Library of Harvard University, the Newcomb Archives holdings not only cover six decades, but they span an extensive body of case law as well. Alongside her well-known work in women’s rights and sexual discrimination, Roberts also tried cases regarding issues in mental health, prisoners’ rights, domestic violence, child protection, and community property rights. While some of these collections may remain closed due to family privacy laws—namely, the files that may contain medical casework—visitors are still encouraged to make use of the collections for purposes such as teaching or research. An archive only lives if it is used, so ensuring its discoverability and accessibility is high on Newcomb archivists’ list of priorities.

A 1976 group photo from a board meeting of the NOW Legal Defense and Education Fund that includes Betty Friedan (front row, second from the left), Muriel Fox (back row, third from the left), Sylvia Roberts (front row, third from the left), and others yet to be definitively identified by Newcomb Archivists.

The addition of Roberts’ papers complements the holdings of other notable activists of the era, archivist Chloe Raub notes. “Women’s activism has been a traditional collecting area for the Newcomb College Archives,” she recently said. “While an acquisition the size of Roberts’ is unique, we do have materials from other second- and third-wave feminist activists, and now that many women graduates from the 1960s and ’70s are retiring, we have seen an increased interest from our alumnae in donating their materials.”

Which raises the question of what a collection such as this—extensive, quiet, and analogue—means for a contemporary generation of activists, what impact it might have on them, and likewise, how their work might be collected and archived in the future. Indeed, one wonders what Roberts would have made of the methods of modern-day activists seeking a more just and equitable society. Certainly she would have recognized the strategies of the marriage equality movement, which earlier this year saw its victory in the highest court in the land. But how she would have framed contemporary efforts rooted as much in social media as public protest—say, the Black Lives Matter movement—or even lesser, awareness-based campaigns such as #BringBackOurGirls or #ICantBreathe and their long-term effectiveness remains an open and provocative question. What we can surmise at the least is this: that Roberts would have cheered these efforts on, understanding that while the tools of activism may have changed over the decades, the basic impulses driving it have not.

Ultimately, much remains to be learned from this collection, and undoubtedly it will yield more treasures once it is fully catalogued and opened to the public. Until then, in the age of social media as preferred soapbox and of causes that can last for days at most (does anyone this week still care about Cecil the lion?), it is undeniably refreshing to encounter the slow, patient, methodical work of an attorney who on innumerable occasions unraveled the twisted threads of power woven throughout our society, a testament to the fact that systematic, meaningful justice can still prevail. If we learn anything from Roberts’ career—even just by considering the courtroom sketch above—it is that nothing will ever change if individuals and communities remain silent. No matter whether it’s an attorney to a judge, a grieving family to a police officer, or even just one concerned friend to another, the first step to any form of change is mustering up the courage to speak.