Right of Refusal: “#ReHumanize, for Albert Woodfox” at UNO St. Claude Gallery

Lydia Y. Nichols reflects on an exhibition by Jackie Sumell and Devin Reynolds and the concept of humanity.

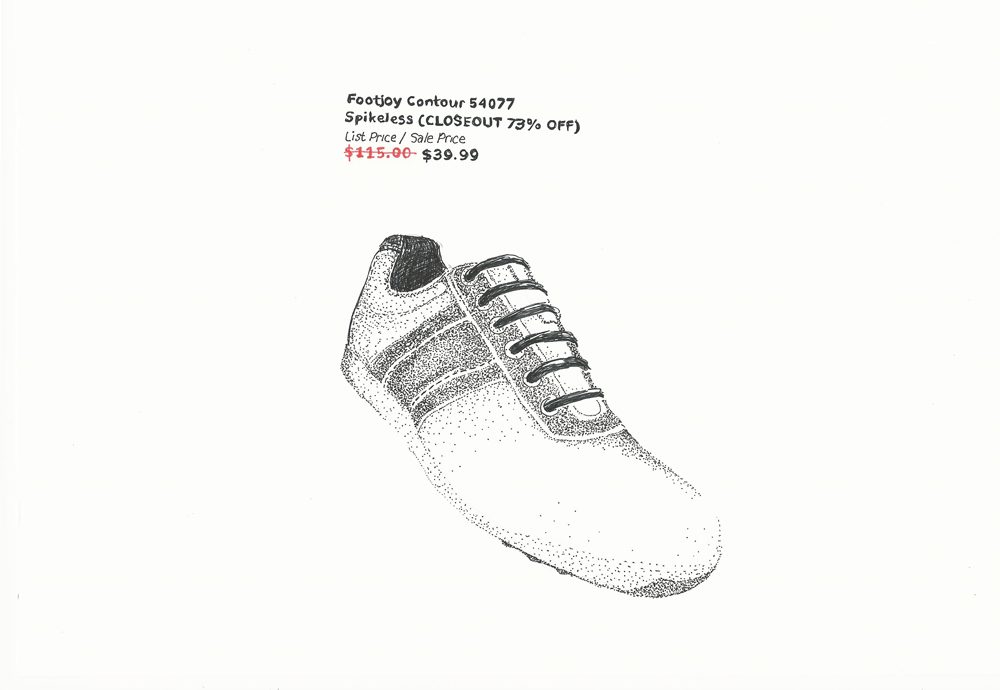

Jackie Sumell, Kijana Tashiri Askari/Footjoy Contour Spikeless Golf Shoe (on sale)/#H-54077 (detail). Two framed works on paper. Courtesy the artist.

Dedicated to Albert Woodfox, the only unliberated member of the trio of black male political prisoners known as the Angola Three, “#ReHumanize, for Albert Woodfox” at the UNO St. Claude Gallery highlights the commodification of those imprisoned by the American penal system. With Jackie Sumell’s delicate drawings and hand-written profiles of former and current prisoners and Devin Reynolds’ jarring, advertisement-like paintings, the exhibition asks viewers “to imagine a world without prisons and to begin to dream of ways to better insure [sic] public safety and wellbeing without the need to simply dehumanize and punish.” “#ReHumanize” does not allow viewers to imagine or to dream; instead, it force feeds them a skewed perception of the “other” to elicit a superficial, empathetic response on the basis of shared humanity with those victimized by the Prison Industrial Complex.

To rehumanize means to make human again. The concept of humanity is a collection of hegemonic values that are projected onto us to regulate social behavior and to perpetuate the status quo; our ability to reflect it and the institutional response to our reflection of it largely depends on where we exist in the socioeconomic matrix. At the intersection of art and activism, those who are best able to reflect the human ideal are endowed with institutional visibility, allowed access to funding and a platform. Thus is born the career social practice artist. The title of the exhibition rightfully suggests that humanity can be given and revoked. However, “#ReHumanize” operates on the deluded beliefs that it is the role of the social practice artist to project humanity onto the “other” and that viewers of these projections can liberate said “other” with their gaze—a delusion many buy into because it is consistent with their savior complex. Reynolds and Sumell fail to realize that their projection of humanity onto prisoners actually prevents the abolition of the Prison Industrial Complex. As long as humanity is the basis for justice and compassion, white supremacy, patriarchy, capitalism, and imperialism—the forces that sustain the Prison Industrial Complex—will continue to thrive.

As an example of the ways in which the prison system dehumanizes, Reynolds and Sumell focus on the replacement of prisoners’ names with inmate numbers. Sumell couples pencil drawings of objects that have stock-identification numbers identical to prisoners’ Department of Corrections numbers with brief profiles of each prisoner. By placing the drawings where viewers might expect an image of the prisoner, Sumell argues that the replacement of names with numbers is evidence of prisoners’ dehumanization. Reynolds and Sumell prove that the concept of humanization is synonymous with colonization when stating in a large manifesto-like wall text that, by having their “real family names” taken away, prisoners are dehumanized. For most black, Latino, and Native-American prisoners, family names were forced upon them by the Europeans who colonized and/or enslaved their ancestors, replacing indigenous African and Indo-American names with European ones, followed by other forms of degradation intended to alienate them from their cultures of origin. The purpose of humanization is to organize and control.

As with the inextricably tied systems of global oppression, compartmentalization and competition power the human ideal. The privileged subject identifies the “other,” in the case of “#ReHumanize,” prisoners, and assesses similarities and differences. Sumell chooses not to detail the reasons why the profiled prisoners are or were incarcerated; she compartmentalizes because to acknowledge a history of crime would limit many viewers’ ability to perceive the prisoners’ humanity. But the prisoners’ crimes are as much an aspect of their humanity as their love for ice cream and walks in nature, which she does include. All so-called crime is a reflection of the human ideal—of hegemonic views regarding women, poor people, people of color, money, liberty, social acceptance, and respect. It is the projection of humanity that lands people in prison in the first place. Yet, Reynolds and Sumell propose that, to counteract the trauma of the prison experience, we must project humanity onto them again.

Installation view of paintings by Devin Reynolds outside of UNO St. Claude Gallery as part of “#ReHumanize, for Albert Woodfox.”

In efforts to rehumanize the people in the St. Roch neighborhood, Reynolds deconstructed the barrier between the community and the gallery by installing over two dozen small paintings on the chain-link, barb-wire fence that divides the gallery’s gravel parking lot and the sidewalk. With a mixture of sadness, bewilderment, and condescension, Reynolds told me that the day before the opening, he arrived at the gallery to find that a piece that reads “MiKKKael Jordan” with the image of a white-hooded Nike Jordan logo had been ripped out of place and hurled toward the building. Unaware that it is the same humanity he is projecting that leads people to want expensive tennis shoes, Reynolds mocks Jordan-buyers’ efforts to reflect the human ideal. Humanization is funny like that.

The strength of the human ideal lies in its transmittable and transmutable nature. The human ideal functions cyclically because our projection of humanity is a sign of our humanity. When we humanize someone, we train him or her to project. A country of humans is a country of complacent slaves deceived by crumbs of access and privilege to ignore the white supremacist, patriarchal, capitalist, and imperialist nature of the humanity that they perpetuate. Once one has been humanized, humanization comes easy. The real work is acknowledging how we have all been traumatized by the projection of the human ideal and working to heal from that instead of continuing to project our trauma onto others by being human and humanizing.

Throughout United States history, the human ideal has been touted by self-proclaimed allies to bring institutional reform. Thomas Jefferson advocated for an end to American participation in the transatlantic slave trade. In a presidential message to Congress, Jefferson described the transatlantic slave trade as “those violations of human rights.” But not only did he continue to own and domestically trade enslaved Africans, he openly opposed private manumission and public emancipation and proposed legislation to outlaw free people of color. Forty-six years later, Harriet Beecher Stowe published her classic novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Though she had never been to the South, Stowe wrote about fictional black characters there to enlist the support of northern white women readers like her for the abolitionist movement. But when Harriet Jacobs, the author of Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, wrote to Stowe asking that she write the preface to her soon-to-be-published slave narrative, Stowe declined because, she said, Jacobs’ inclusion of extramarital sex (a relationship that Jacobs explains in the text she had to protect herself from getting raped by her owner) was un-Christian and undignified.

Neither the transatlantic slave trade nor domestic slavery was abolished because of African people. And to be clear, only one was abolished at all. The United States abolished the transatlantic slave trade to sever economic ties with Britain, the largest international trader of enslaved Africans, and to accelerate the domestic slave trade. The United States reformed slavery (enter: the Prison Industrial Complex) because free slave labor in the South impeded the economic growth of the industrial North and threatened the stability of the Union. The transatlantic slave trade was abolished and slavery was reformed to protect humanity—that is, white supremacy, patriarchy, capitalism, and imperialism. The revolution will not be led by humans.

Oppressed people are conditioned to seek evidence of our humanity in the gaze of those who best reflect the human ideal, and in doing so, we alienate ourselves from the people who are capable of seeing us for who we are and not for our potential to be more like them. From the Big House to the Ivory Tower to the six-by-nine-foot cell that Albert Woodfox has been kept in for 43 years, we’ve long known privilege is a joke, but it’s a narcotizing one if you’ve got it and an appealing one if you don’t. When we relinquish the need for validation, when we relinquish the desire to be perceived as human, that is when we unite. We seize control of Attica. We set fire to sugar plantations in Saint-Domingue. We slice throats in Virginia. We throw trashcans through the window of Sal’s Pizzeria. Our actions seem illogical to some, riotous. Unhuman, unreadable, we see each other.

Reynolds and Sumell command us to rehumanize. I refuse.

Editor's Note

“#ReHumanize, for Albert Woodfox” is on view through September 7, 2015 at the UNO St. Claude Gallery (2429 St. Claude Avenue) in New Orleans.