Tripwires

As part of our ongoing series exploring wellness, healing, and care, Jessica Morey-Collins reflects on a traumatic plane ride from London to Accra and questions how distress and memory remain in the body.

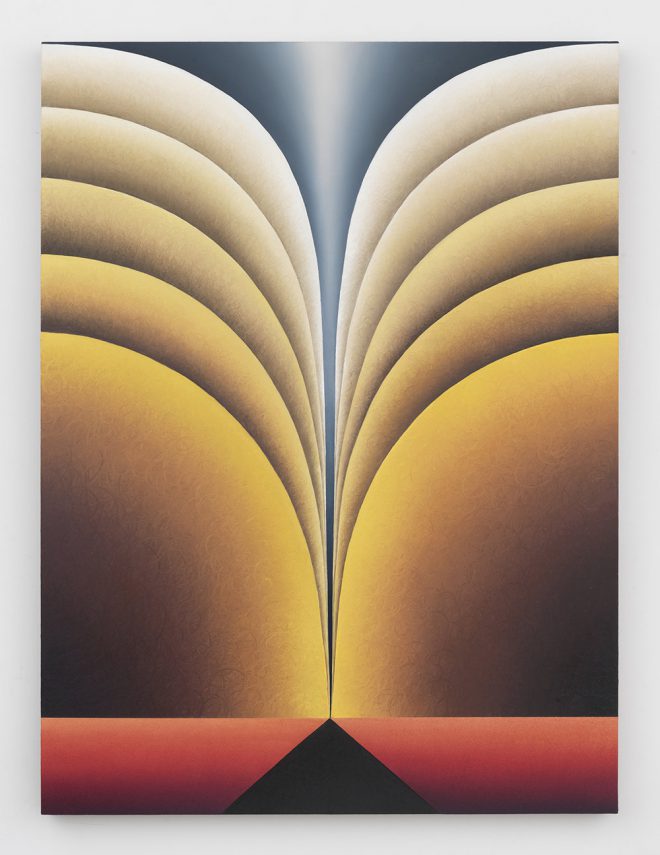

Loie Hollowell, Yellow Mountains, 2016. Oil, acrylic medium, and sawdust on linen over panel. Courtesy the artist and Pace Gallery, New York.

“You’re victim-blaming,” Tim typed.

Sitting at the front desk of my office, I stared at the cursor blinking in the Gchat send space. I could feel my brain peel away from the sides of my skull and settle in the center of whatever fluid (ire? apathy?) had filled me up so suddenly.

I was confiding to him about my savior complex. The whole reason I’d gone to Ghana was to gain some global understanding that might enable me to be a hero. I didn’t exactly imagine myself in tights, but seven years after my semester abroad, that rhetoric of wanting to be lauded now makes me itch. When I decided to spend that semester in Ghana, I honestly wasn’t thinking much about the people who lived there.

Nor did I think much about the culture I was about to immerse myself in. I did no research. Then, I passed out drunk on the plane ride between London and Accra and woke up with a 55-year-old man’s hands down my pants, squeezing. I talked to the program staff—mostly Ghanaians and a few Canadians—about what happened and was told point-blank that if I didn’t want to have sex with him, I shouldn’t have had a drink with him. If I didn’t want to “be romantic” with him, I shouldn’t have talked to him. I was sending clear signals—what did I expect?

Years later, their rhetoric strikes me as patronizing. To him. Is it fair to assume that a man of another culture is less capable of interpreting consent? Still—if I had been more focused on understanding Ghanaian customs and less focused on how cool I would seem for having been to Ghana, maybe I’d have been more aware of his intentions. I was bemoaning my self-absorption and megalomania when my then-boyfriend accused me of victim-blaming.

Could I victim-blame myself? Sure, I had been doing so for years. (But if I’d been more aware. But if I’d been sober. But if I’d read up on the culture. But if I’d kept to myself. But if I hadn’t been too friendly. But if I hadn’t been too friendly. But if I hadn’t been too friendly.) Would I ever, ever say these sorts of things to another person who’d been assaulted? Absolutely not. But could I overlook my agency in my own sexual assault? Was it necessary for me to claim blamelessness? Would negating my role in what happened somehow lead to more holistic healing? I’ve been asking these questions for over seven years.

In early January of 2009 I settled into the window seat of a Boeing 777 bound for Accra, Ghana. I ordered a Bloody Mary, which was always my grandfather’s airplane drink. I was 20 years old.

The night before Tim told me I was victim-blaming, I woke up at three in the morning overheated, agitated, with the phrase “For a long time I wanted to be a savior” ticker-taping through my brain. My torso was hot and slick against the New Orleans summer. It was June of 2015. My ribcage radiated heat. My heart vibrated.

I’ve woken up like this for seven years, now, with a slowly unwinding frequency. Immediately after the assault, I would wake up several times every night.

For the first year, I had PTSD-induced nightmares in which I accidentally killed or mutilated family members every single night. I was terrified of falling asleep. I would wrench myself away from sleep with reading and with desperate, unpleasurable masturbation.

And it’s not always the same phrase that ticker-tapes through my mind. For a while it was “I watched the Sahara slide under the airplane while he plundered my body,” but that wasn’t quite right. My ethnic legacy is colonial; my attitude toward otherness often veers into appropriation. Sometimes the phrase is “Penance my penance my penance, I’ll pay for us all, I’ll swallow it whole, I promise.” Often it’s “Geoffrey’s papery hands ripped through me and took the good.” Sometimes it’s “I plunged into my first new country un-whole, unwholesome.” There are more phrases than I catalogue—but it’s almost always language that shakes me awake.

In the worst of the PTSD nightmares, I’m having sex with someone, anyone, and, mid-fuck, the person turns into my father. Then my father refuses to stop. For the first year after my assault, I had this dream weekly. Awake, I found it hard to hug him. It took me nearly two years to tell him I loved him. I’ve still never told him about this dream. I hope he never finds out.

In an attempt to unravel this nightmare, my therapist suggested I ask family members about my early childhood. Was I sexually abused and blocking it out?

I approached my grandparents with open-ended questions. My dad’s parents were quick to tell me how my mother, strung out or struggling with recovery, was eager to get rid of me each weekend. They assured me, though, that I was a happy child—well loved and cared for. I was verbose, silly. My mom’s mom was quick to tell me how, in many ways, I raised my mother. I would pull at my passed-out mom, trying to get her out of bed. My grandmother said it broke her heart. She also told me that one weekend I came home from my dad’s house with a badly bruised vulva.

My recovery became intractably tangled with the possibility of early-childhood trauma. A single event tugged on a single thread that revealed itself to be woven into all other aspects of my being.

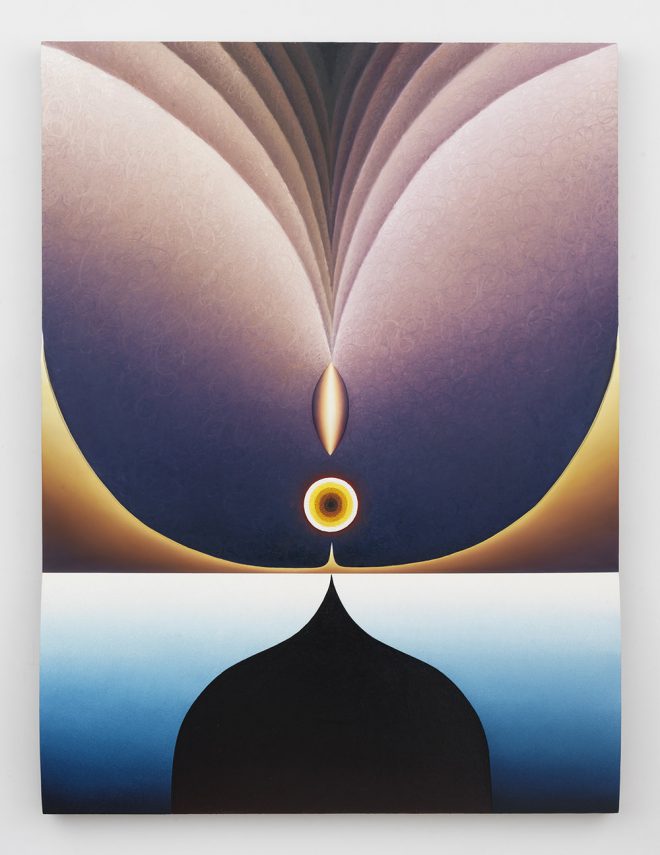

Loie Hollowell, Incoming Tide, 2016. Oil, acrylic medium, sawdust, and high-density foam on linen over panel. Courtesy the artist and Pace Gallery, New York.

That summer, Tim and I had an ongoing argument about the HBO series True Detective.

“Imagine a show that treated men the same way that women are treated in True Detective,” I said.

“I think it’d be refreshing,” Tim said.

If eye-rolls were audible, that one would have sounded like a Boeing 777 roaring overhead.

The argument started because a few weeks before, Tim had picked the movie Oldboy for us to watch—a 2003 Korean neo-noir thriller/mystery. He picked Oldboy because I’m artsy and had lived in Asia for a few years, and because I like gritty things. He knew I had been sexually assaulted and prefer a heads-up about certain types of violence. He told me that there was gratuitous violence, but nothing really sexually violent.

About 30 minutes into the movie, a woman is stripped and her breasts are groped by a group of men. Tim paused the movie and turned to me, visibly concerned, remorseful.

“I’m so sorry,” he said, “I was 16 when I watched this before. I didn’t remember this scene.” I assured him it was okay and we continued watching.

The movie is basically a revenge plot—in which a man has been kept hostage for 20 years, and uses that time to transform himself into a warrior. Upon his inexplicable release, he meets and falls in love with a beautiful, young sushi chef, as he fervently seeks revenge upon his former captors.

As the plot thickens and writhes, a brutal twist begins to feel imminent.

It turns out the love object is the protagonist’s daughter—that they had both been held captive by a vengeful, incestuous mastermind seeking out a pointed retribution for being outed by the protagonist—decades prior—for having had sex with his sister.

I tried to keep it together.

Tim was going to meet my father in a week. I was in love with Tim. I didn’t want him to know about my PTSD dream. Not yet, at least.

I strained to hold back my tears.

I was humiliated by my emotional response.

I fractured.

In early January of 2009 I settled into the window seat of a Boeing 777 bound for Accra, Ghana. I ordered a Bloody Mary, which was always my grandfather’s airplane drink. An older man wearing a beret, glasses, and pressed khaki pants settled into the seat next to me. He commented on my drink. (“You like vodka!”)

He introduced himself as Geoffrey. He was 55 years old and married, had four children. He was born in Accra but had lived in London for the last 15 or so years. We chatted amiably, then I put on my headphones and watched the first half of Braveheart.

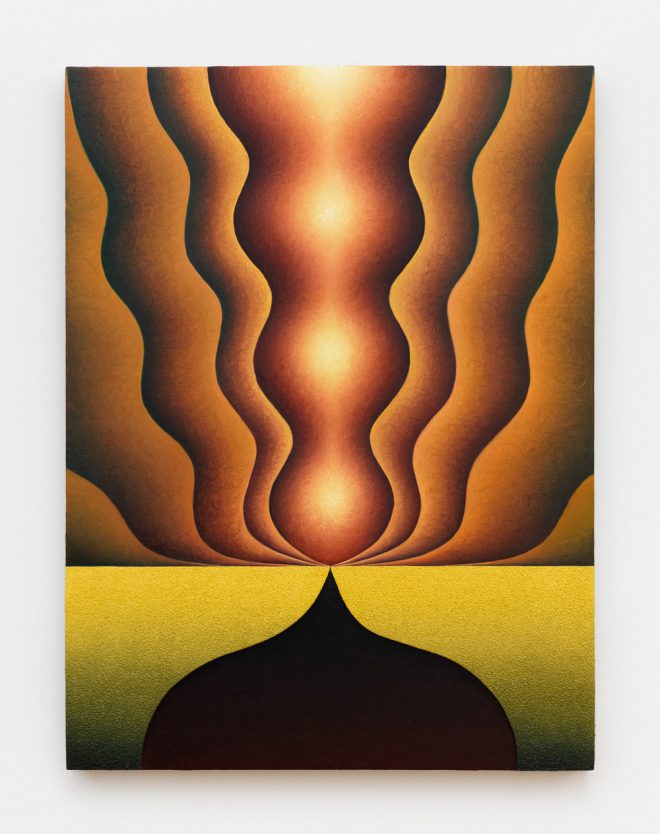

Loie Hollowell, Deep Canyon, 2016. Oil, acrylic medium, sawdust, and high-density foam on linen over panel. Courtesy the artist and Pace Gallery, New York.

After Oldboy, Tim was determined to pick something that I liked. He was positive that True Detective would be a hit. It had all the things. It was artfully shot, spooky, mysterious. It centered around the murder of a prostitute, but I knew that up front. But the real draw was that he knew “a lot of feminist women” who liked it.

This automatically put me in an adversarial mindset. It’s not that I doubt the feminism of Tim’s friends, or even Tim’s own feminism. But if I’m told I’m supposed to like something, my knee-jerk impulse is to find a reason not to.

Luckily for me, True Detective provided amply.

Not only did it miserably fail the Bechdel Test, but in the first four episodes, women were almost exclusively presented as objects—romantic, sexual, dead—and the frequency of sexualized female nudity (and the near exclusion of likewise-sexualized male nudity) made the show easy to criticize.

Tim understood my criticisms of the show, but assured me that the show was “objectively good,” citing the series’ many accolades, and, again, the appreciation of his many sophisticated female friends. Furthermore, the show was accurate. Wouldn’t a 1990s police station in southern Louisiana lack a professional female presence? Did I expect the writers to change history to appease a certain viewership?

The question pulsing under his rhetoric: Why can’t you be cooler about this?

In early January of 2009 I settled into the window seat of a Boeing 777 bound for Accra, Ghana. I ordered a Bloody Mary, which was always my grandfather’s airplane drink. An older man wearing a beret settled into the seat next to me. He introduced himself as Geoffrey. He was 55 years old and married, had four children. We chatted amiably, then I put on my headphones and watched the first half of Braveheart.

Halfway through the movie I took off my headphones. Geoffrey asked how I liked the movie, and we spent the next few hours talking about the credit crunch, the looming environmental crisis, his experiences as an expatriate, Ghanaian weed culture, poetry.

He waved over the flight attendant and asked for more drinks. After two more, we switched to wine. It would be rude for me to turn down a drink, he told me. I remember taking note of this. Literally, I remember noting it in the Moleskine I’d carried with me. I was eager to be accepted, so jotted down any custom Geoffrey mentioned. Graciously accepting hospitality. Snapping fingers when you shake hands. Eating the food that was offered to me.

I should visit him in Accra, he said. He could show me where to get weed. He wrote his name and phone number in my Moleskine.

Eventually, when the flight attendant said he would no longer serve us alcohol, Geoffrey walked back to the storage compartment and loaded his pockets with tiny bottles of vodka and rum. He lined up the bottles on the edge of my plastic tray table. It would be rude to say no, he smiled.

I stayed at a hostel in Brooklyn for two days before my flight to Accra. I wrote happy poems about the empowerment of solitary travel, the helpful good-heartedness of other humans. I remember writing in my Moleskine: “You’re a human, I’m a human, let’s smile at each other.” I remember that I felt very original and righteous writing that sentence. I remember re-writing the word “let’s” in big, flowery calligraphy.

Loie Hollowell, Thick Pound over Green Mound, 2016. Oil, acrylic medium, sawdust, and high-density foam on linen over panel. Courtesy the artist and Pace Gallery, New York.

A few days before my dad and stepmom arrived in New Orleans, Tim and I drove back from City Park, where we’d just gone for a run.

“I know he didn’t do it,” I told him as I keyed up the ignition.

Tim and I shared a car that summer, and I hated being passenger. I’d been in New Orleans for a year and finally knew the potholes and buckled pavement of my neighborhood. Whenever he drove, I spent the whole ride tense, barking out warnings. My shitty, dysfunctional SUV was the most expensive thing I owned, and I needed to be in control.

After we watched Oldboy I had told Tim about the dream, my therapist, my family’s accusations. I had told him that I was confident that my father never sexually abused me. But I was emotionally exhausted and hadn’t wanted to unpack the whole story.

The drive back to my house only took about five minutes, but I needed to feel in control of something while I explained.

There was a lot of animosity between my mom’s and my dad’s sides of the family after the divorce, I told Tim. I was two at the time. Both had admitted to getting physical when they fought. Both had been using drugs. Parents and grandparents and aunts and uncles openly shit-talked each other for my entire life, which stoked my confused adolescent self-loathing and a perpetual state of distrust and discomfort. I never knew who to believe. Each family believed itself to be the better, more functional set of people.

When my mom’s mom told me that I’d come back from my dad’s house with a bruised vulva, I went immediately to my dad’s mom. She remembered. My dad was living with her at the time, so I spent my weekends with her.

I was super into horses at that age. My paternal grandmother told me that she had taken me, my cousin, and my aunt on a walk to a neighbor’s yard to feed carrots to their horses. I was climbing the fence to get closer when I slipped and the bar slammed into my crotch.

My maternal grandmother had called the police and had my dad taken in for questioning. My paternal grandmother, aunt, cousin, and me all vouched for the horse/fence/crotch story, though I have no memory of the event now. At 21, when I was working through my PTSD with a therapist, I verified this account with my grandmother and aunt before going to my dad. He was enraged that this was coming up again, vehement that he had never, would never hurt me like that.

My mom and her mom refused to believe that anything but sexual abuse led to the bruise. To this day they maintain that someone on that side of the family molested me. At 21, dreams of incestual rape prevented me from having a functional relationship with my father.

When Tim and I got back to my house, my roommates’ cars were gone. In the privacy of their absence, I finished relaying this story standing just inside the front door of my house, out of the oppressive heat.

I wondered how Tim or anyone could love someone like me, someone with a complicated set of tripwires and personal politics informing her psychology. Someone with so much self-pity. But Tim was just angry on my behalf. I wondered how long his patience would last.

In early January of 2009 I settled into the window seat of a Boeing 777 bound for Accra, Ghana. Six hours later I woke up in the dark fuselage with paper-dry fingers prying open my vagina, a sticky tongue dragging across my teeth. I turned away and pressed my face to the window and watched the Sahara Desert ripple far below.

Ultimately, I decided to believe my father. His support had been instrumental in my education, my access to mental healthcare, my travel. And having lived with him and my step-mom for my last two years of college and the first two years of my professional life, I had no reason to suspect that he was anything but a happy, devoted husband, father, and educator.

Tim and I had to circle the airport several times before my dad and stepmom were ready with their luggage. On the third-to-last lap I saw them—Dad in a bright blue T-shirt, Jody tall and curly-haired in a floral print. It had been almost a year since I’d seen them last, and my stomach did a little flip.

We spent the next week between oyster bars and bar-bars. We took a ghost tour and a swamp tour. We ate Cajun-Italian food at Adolfo’s, then walked Frenchmen. We dipped into Vaso and, after a cocktail, Jody and I got up to dance. After one song, my dad and Tim joined us. It was a pretty goofy group dance and only lasted for one song before my dad and Jody went to sit down. To other people it probably looked like your standard awkward family-vacation situation, but being so embodied around both my dad and my boyfriend was a testament to my okay-ness.

When the Boeing 777 landed in Accra I stayed curled up with my face pressed to the window until a flight attendant tapped me on the shoulder and asked me to leave. The sweaty, equatorial air of Accra already filled my lungs. I scrambled to collect my things, but my Moleskine was gone. I looked under and between the seats, in the seat-back pockets. I asked the flight crew if they’d seen anything; they hadn’t.