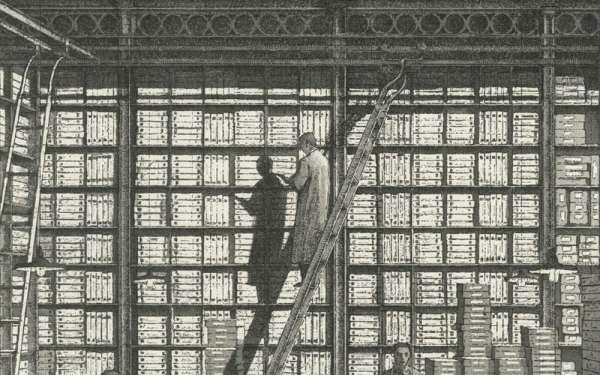

Site, Specific: Dr. Charles Smith and the Archival Impulse

Allison Glenn visits Dr. Charles Smith’s African American Heritage Museum and Black Veterans Archive in Hammond, where the artist aims to tell forgotten histories of the African diaspora.

Dr. Charles Smith’s African American Heritage Museum and Black Veterans Archive in Hammond, Louisiana.

Dr. Charles Smith’s African American Heritage Museum and Black Veterans Archive is an art environment located approximately 60 miles northwest of New Orleans in a residential neighborhood in Hammond, Louisiana, just a quick jaunt from New Orleans across the Causeway Bridge and then west on Louisiana Interstate 12.

At the intersection of East Louisiana Avenue and South Walnut Street, the breathtaking installation takes form. Starting with a chronological narrative, Dr. Smith creates allegorical vignettes that visually reference specific periods in history. The front of the house has a mausoleum-style façade, with a stoic face emerging from the center of a triangulated structure that references a perceptive third eye. Two smooth, concrete steps lead to a set of French doors flanked on one side by a high-relief sculpture resembling an ancient Egyptian ushabti, or funerary figurine. The black and white undulating lines of various thickness that comprise the decorative clothing of this figure continue along the front of the house. Embedded into the center of the second step are the words “Trust God.” Two female characters wearing red-white-and-blue-painted shirts sit in lawn chairs on either side of the steps, their raised hands holding American flags. Anthropomorphic forms continue to emerge from the side of the house, the low-relief busts an homage to Hurricane Katrina survivors.

Dr. Charles Smith’s African American Heritage Museum and Black Veterans Archive in Hammond, Louisiana.

From the walkway to the exterior walls, every inch of the landscape has been considered. A curvilinear path snakes around the yard through the labyrinthine environment, punctuated by the artist’s sculptures. Dr. Smith’s installation visually communicates a history of the black diaspora, starting with the Middle Passage and ending with a small cluster of in-progress pieces, the figures’ hands raised, poised to carry the flag poles that the artist assured me they would normally be holding. When I visited last November, a stack of yard signs with early voting reminders for the presidential election lay next to these incomplete works. Serious attention is given to the objects themselves. From the texture of his subjects’ hair to the varying tones of their skin and their facial expressions—every inch of their thick surfaces are willfully designed.

The beauty of Dr. Smith’s project is that it is at once an installation and the artist’s studio. Smith, a self-taught artist and Vietnam veteran, has honed a multi-step sculpting technique that is created by mixing cement and other materials. Once the creation of the anthropomorphic forms is complete, they live in his yard until it is time to paint and decorate them for exhibition either in the home on the property or at an off-site location. Many of the sculptures, and therefore the entirety of the project, live in various forms of completion. This leaves the land in a constant state of flux, which is the nature of this part of the country. Last year’s flooding in this area has completely ruined the interior of Dr. Smith’s studio and archive, and during my visit to the site, Dr. Smith assured me that the site is usually in much better condition.

Dr. Charles Smith’s African American Heritage Museum and Black Veterans Archive in Hammond, Louisiana.

Located approximately 40 miles west of Chicago, in Aurora, Illinois, sits the original installation of Dr. Smith’s museum. Early on in his development of the site in Aurora, Dr. Smith knew he had to channel the anger and post-traumatic stress that he was experiencing as a result of his military service into something productive. The larger thematic arc of both sites is to make visible that which has otherwise been rendered invisible. Smith’s project taps into the rich history of house museums, arguably born out of the desire to control the shape and development of the narrative around collections. But building a legacy is no easy task. The artist conceived of the site in Hammond in 2000 after being struck by a tombstone in the city that had the words “UNNAMED SLAVE BOY” inscribed in capital letters on the surface of the modest, rectangular form. As Dr. Smith shared with me on my visit, the child was the “favorite slave boy” of Peter Hammond, the Swedish founder of the city. The artist immediately felt that his impact and calling was to create a reparative history that allowed for contributions of the black community to be honored, shared, and accounted for.

Dr. Smith’s practice is a great example of an artist who works with the built environment, both its physical and social manifestations. There is a conceptual link between the work of Dr. Smith and that of artists like Torkwase Dyson, Tyree Guyton, Rick Lowe, Olayami Dabls, Theaster Gates, and Heather Hart—who is creating a response to this site-specific architecture for an exhibition of Dr. Smith’s works this fall at the John Michael Kohler Arts Center in Sheboygan, Wisconsin. At the core of these artists’ desires to activate the landscape is a critique of land-use policy and urban development and to channel the subsequent socioeconomic impact that those critiques can have on a local, national, and international level.

Dr. Charles Smith’s African American Heritage Museum and Black Veterans Archive in Hammond, Louisiana.