Detective of the Impossible: Norah Lovell at Staple Goods

Joseph Bradshaw contemplates the influence of Max Ernst and Roberto Bolaño on Norah Lovell’s recent paintings.

Norah Lovell, Seaside Crimes 2, 2017. Gouache and Flashe on panel. Courtesy the artist.

Deriving its title from the sordid universe of Roberto Bolaño’s 2666, Norah Lovell’s “The Minor Works: 100 Paintings” is a series of diptychs inspired by crime. However, Lovell’s miniature gouaches are quite unlike Bolaño’s unfinished epic, which faces directly humanity’s darkest impulses in hundreds of pages of frank descriptions of murder, rape, manipulation, and torture. Instead, the element of crime in Lovell’s paintings is suggestive: A subtle air of menace and lasciviousness hangs over the panels, with echoes and motifs that blend the banal with the phantasmagoric, in a muted color scheme that seems more at home in a Pottery Barn catalogue.

The choice of imagery is partially explained in the exhibition statement, where Novell’s image bank is listed as “twelve panels of mysterious 19th century French wallpaper, [and] World Book encyclopedias circa 1970.” From these sources she culls antiquated images of people and animals, arrayed in various domestic scenes. Within each diptych, Lovell subtly shifts the points of view of the scene, creating an eerie sense of dislocation. A man enters an apartment door in one painting, while in the next a woman stands on the other side of the door. What makes the shift unsettling is the image that occupies both sides: a line drawing of a fangy dog, a kind of Hound of Hell that hovers over the scene, embodying the spirit of menace. A careless eye might glance over the line drawing, as its coloring blends it with the background—making it, funnily enough, like wallpaper.

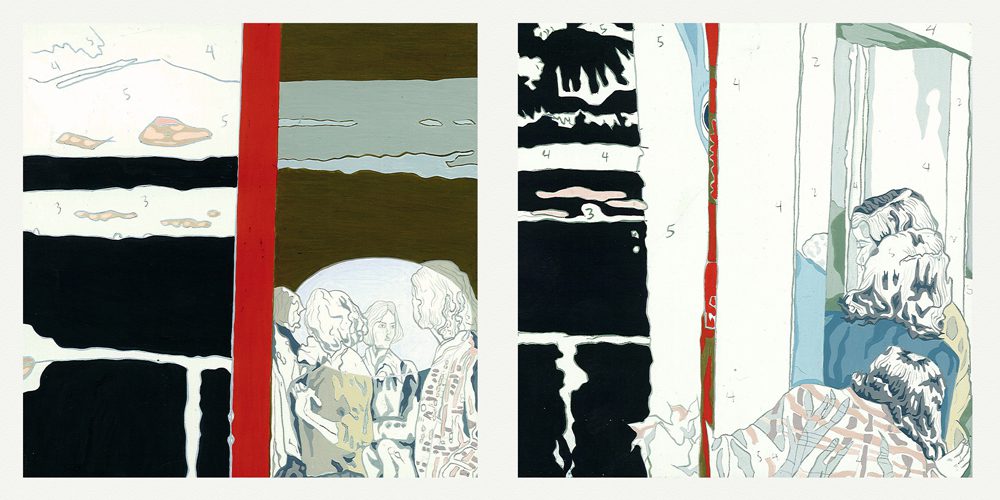

“The Minor Works” asks for—even demands—careful attention. Each panel is a uniform five-by-five-inch square filled with overlapping images that morph and blend into one another. The yellow of a woman’s skirt in one panel is echoed in the coloring of a crustacean in another, which is echoed elsewhere in a colonnade or a car. These tonal shifts, while connecting themes and creating a unified sensorium, do not lead to a cohesive narrative. The images Novell presents are clues to unsolved, and perhaps unsolvable, crimes. But part of the pleasure in viewing these pieces is in assuming the role of a detective of the impossible: The viewer can try to add up the clues, to connect all the fragments, all the while knowing there is nothing to add up.

One visual element that occurs in nearly all the paintings is a series of digits in stark areas of the panels, suggesting paint-by-numbers. It cleverly underscores several themes of the show. Painting by numbers is an innocent (and dated) pastime—an innocence ironically contrasted with the portentousness of the imagery. The presence of the numbers suggests that the paintings are unfinished, which reflects the unknown and unknowable crimes they depict.

Norah Lovell, Riverside Crimes 5, 2017. Gouache and Flashe on panel. Courtesy the artist.

The numbers also suggest that these paintings are studies, or perhaps copies, an idea that connects to Bolaño’s conception of the “minor work.” A failed writer, one of the characters of 2666, explains that “literature doesn’t consist solely of masterpieces, but rather is populated by so-called minor works.” Each minor work, he goes on to say, is written by “a secret writer who accepts only the dictates of a masterpiece.” The failed writer later rephrases this as an aphorism:

Jesus is the masterpiece. The thieves are minor works. Why are they there? Not to frame the crucifixion, as some innocent souls believe, but to hide it.

Lovell’s framing of the show as “an exploration” of Bolaño’s idea of the minor work is puzzling. Is she taking the stance of that “secret writer” and painting under the dictates of Bolaño’s repressive masterpiece? Or is she like one of Christ’s thieves, who “hide” the crucifixion? Lovell’s references to 2666, both explicit and allusive, add another layer of instability to “The Minor Works.” The total refusal of stable reference points evinces a deep suspicion of pictorial representation, of the ability of images to mean anything definite. It also distinguishes the show from other art made in response to literary masterworks, such as Zak Smith’s Pictures of What Happens on Each Page of Thomas Pynchon’s Novel Gravity’s Rainbow, 2004, which does exactly what the title says it does, in images that range from abstract thought-bubble explosions to multi-paneled cartoons depicting rough sex.

There is a long history of works like Lovell’s, which has a mainspring in Max Ernst’s 1934 novel-in-collage, Une semaine de bonté, a notable precursor to the graphic novel. Many of the stylistic techniques in Lovell’s show are inherited from Ernst, who restricted his image bank to the antiquated Victorian novels and encyclopedias that were plentiful in 1930s Europe to create a series of collages that are visually unified, but which resist narrative. Thematically his collages, like Lovell’s paintings, suggest trauma and terror without directly depicting the scene of any crime.

It would be shortsighted and unfair to say of a contemporary artist who swims the waters of the absurd that they are derivative of classical Surrealism. It’s kind of like saying a pop band that uses 4/4 rhythm and two-part harmonies is just a pale Beatles. Such a statement ignores the intricacy and minutia of an artwork’s personality—and the delight of “The Minor Works” is in its intricacies and minutiae. All the same, it is Ernst’s masterpiece, not Bolaño’s, that casts the longer shadow over “The Minor Works.” Does the presence of that shadow matter? The title of Lovell’s show, true to its ambivalence, says both “yes” and “no.” It suggests that questions of influence and judgment are just as vague and indeterminate as the crimes that haunt Lovell’s diptychs.

Editor's Note

Norah Lovell’s “The Minor Works: 100 Paintings” is on view through February 5, 2017, at Staple Goods (1340 St. Roch Avenue) in New Orleans.