Systems and Consequences: Michel Varisco’s Gulf Coast

Editor's Note

This review was originally published in July 2012, but we’re revisiting it as part of our thematic series in conjunction with Erin Johnson’s “Of Moving and Being Moved” at Pelican Bomb Gallery X. To further explore ideas central to the exhibition, we’re publishing new reviews, personal essays, interviews, and digital artist projects exploring the many different ways we live with water. We also want to use this opportunity to highlight previously published pieces from our archives, which have documented our ongoing conversations on water.

Michel Varisco, Levee, Happy Jack, LA, 2011. Dye sublimated prints on polysilk. Courtesy the artist.

Systems are hard to photograph, but consequences are not.

Rebecca Solnit, from “The Invisibility Wars”

Teams of photographers from around the world captured scores of aerial images of the brownish-maroon streaks and blobs sprawling across the surface of the Gulf of Mexico in the few weeks after the Deepwater Horizon oil rig blew up (before federal agencies, at the behest of BP, limited access to the airspace). Global news and online social networks disseminated the photographs, providing visual accompaniment to the figures we heard rising and rising over the course of nearly three months, far beyond our grasp of the spill’s potential magnitude—one, then two, up to nearly five million barrels of oil (more than 200 million gallons) escaped from the broken wellhead before it was capped on July 15, 2010.

The images depicted a bizarre world, barren besides the mechanisms of the oil industry and the spill recovery effort—tankers and drilling platforms, floating dams around barrier islands, giant boats spraying chemical-white dispersant in what might have been triumphant-looking arcs had it not been for the vastness of the surrounding seascape and the swath of oil they were meant to attack. The disaster’s sheer scope made the tiny dots of human creation on top of it seem monstrous or pathetic, depending on their function. How could such a small well cause such a nightmarish mess, and how the hell are those puny boats going to do anything to stop it?

Philosopher Timothy Morton has written extensively on the concept of “hyperobjects,” physical things that are so large that they exist outside our comprehension, that “stretch our ideas of time and space, since they far outlast most human time scales, or they’re massively distributed in terrestrial space and so are unavailable to immediate experience." Morton categorized the BP oil slick as a hyperobject, something that not only “radically undermines our ideas of being in charge," but defies our ability to even understand what we have done. Given these circumstances, it is unsurprising that no iconic aerial image of the spill emerged to satisfyingly capture the situation’s essence and that photojournalists shortly gravitated toward the tried-and-true front-page tearjerkers—shots of soiled pelicans and otherwise pristine marshes and beaches sotted in crude.

New Orleans-based photographer Michel Varisco attempted to transcend the limitations of this context by doing precisely what Rebecca Solnit claims is so difficult: photographing systems. Varisco’s exhibition “Shifting,” on display at the Ogden Museum of Southern Art, is the culmination of years of work capturing images meant to illustrate the degrading of the Gulf Coast, which is literally dissolving into the sea. The systems upon which she focuses are the Mississippi River Delta’s process of building islands, jetties, and lakes by depositing silt and clay washed downstream from America’s heartland, and the converse process of oil and gas extraction from offshore rigs in the Gulf of Mexico, which hampers the Delta’s land-building work. The rigs are connected to mainland infrastructure by pipelines running through canals cut into the marshland that suck saltwater into habitats of brackish- and fresh-water plants. The vegetation’s consequential death results in the absence of root systems to hold soil together and the land simply washes away—similar to how arid land blew away during the Dust Bowl—displacing the humans and animals the habitats sustained. Toward what was supposed to be the end of her long project, the spill began. “After the BP blowout,” Anne Gisleson wrote in The Believer, “[Varisco’s] project, already a meditation on the loss of an essential and enigmatic landscape, took on an accelerated urgency." After years photographing systems, the spill provided Varisco the opportunity to document these systems’ very visible consequences.

“Shifting” occupies one of the large main galleries on the Ogden’s top floor. Contrary to what one might initially surmise, her photographs are not traditional nature or landscape photographs. They are photographs of functioning systems, and therefore photographs of events: the Mississippi shifting, the wetlands melting, human machinations encroaching on the natural world. Most of the photographs are mounted in such a way that they seem to float off the wall, and some have been partitioned into segments, printed on polysilk and hung like banners, completely removed from the stability of a support structure. The aerial photographs of land and water split into segments and floating call to mind Pangea drifting apart, and, truly, the process that Varisco explores is one of geo-historical significance.

Solnit’s essay in which she discusses photographing systems is an introduction to artist Trevor Paglen’s book Invisible: Covert Operations and Classified Landscapes. She writes about the integral parts secrecy and invisibility play in the United States’ ability to remain perpetually at war, and how Paglen’s images, for which he used high-powered lenses to photograph top-secret military bases hidden in plain sight, work against this. The oil and gas industry depends on invisibility in a similar way—its operations, almost as a rule, are in far-flung places, essentially removed from public sight and, therefore, public mind. The proliferation of offshore drilling falls squarely within this framework. It allows oil and gas companies to work outside of public scrutiny and, at the same time, to erect rigs without directly spoiling natural landscapes. Varisco’s aerial photos of the BP oil spill make visible the potential catastrophic consequences of this system, and her aerial photos of the Mississippi Delta wetlands crisscrossed by unnatural waterways further flesh out the big picture. Her project exposes the lie that offshore drilling preserves land by showing how, rather than spoiling it, it simply makes land disappear.

Erosion, of the Gulf Coast variety, breeds a particular anxiety. What is most upsetting about the disappearing wetlands is not that we’re losing protection from storm surges or habitat for waterfowl. Those things are true, but they are the talking points of scientists and bureaucrats. In simple human terms, the most unsettling part of the Gulf’s erosion is that we are losing the land on which we live. Humans are terrestrial creatures, and even those who depend on the sea for their living must retreat to dry ground. We have as much at stake in the loss of habitat as any egret or thrush. I am reminded of the epigraph in John Jeremiah Sullivan’s book Blood Horses, for which he quotes Joachim Seyppel on Kafka: “[Kafka] had a sincere awe of the beasts around us, and he considered himself essentially on the same level with them, very closely related—not through evolution, that poor man’s religion, but through common destiny.”

This epic sense of loss and togetherness with the rest of the natural world is most apparent in Varisco’s exhibition not in any of her images, but in the gaps between the six segments of her gigantic print of an aerial photograph of Lake Borgne, which is hung, banner-like, along one of the gallery’s end walls. Unlike a photo of Happy Jack Levee in the hallway outside the gallery that is similarly segmented but clearly maintains continuity between the portions, the large photograph of Lake Borgne appears to be missing pieces in between the segments. At first glance, it looks like a continuous body of land abutting water, but upon close inspection, the meandering lines created by the coast’s edge do not line up. The optimistic view of this effect is that it portrays a vision of a dreadful future, when, in reality, it is more likely an accurate comment on our dreadful, ongoing present.

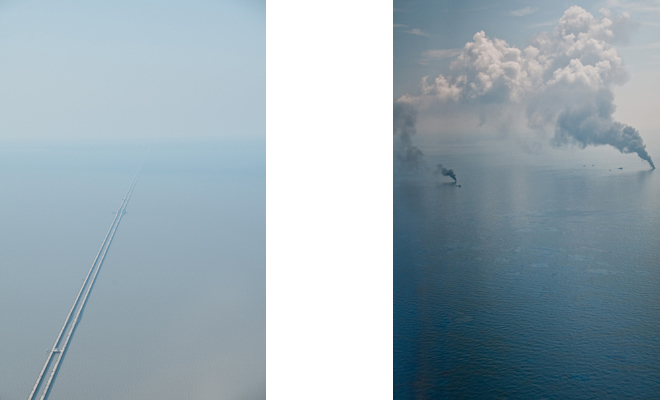

Michel Varisco, Causeway, 2011 (left) and Oil Burns in the Gulf, 2010 (right). Both face-mounted archival chromogenic photograph with dibond backing. Courtesy the artist.

Varisco has said she chose to use wide angles when photographing the rigs and the spill recovery from the air in order to properly depict the fact that they are small, and the ocean and spill huge. Her photographs accomplish the visibility-making function of disaster photography, but they also leverage the transformative qualities of aerial photography’s dramatic shift in scope—familiar details are obliterated by distance while new ones emerge. In Oil Burns in Gulf, 2010, smoke plumes from burning offshore rigs point to their origins like stationary tornadoes in ways similar to those in wide-vantage photographs of well fires in the deserts of Kuwait during the first Gulf War. In Causeway, 2011, the bridge that connects New Orleans to the north shore of Lake Pontchartrain appears as two slim, clean modernist lines disappearing across the lake into an innocuous white haze. Its link to Varisco’s larger project comes with the understanding that the roadway, one of the world’s longest bridges, was built in service to the same outlandish car culture that necessitates oil rigs in the Gulf.

A number of writers, such as Curtis White, have argued that the conversation about our ravaged environment has been hijacked by scientists, businesspeople, and politicians is such a way that the true essence—the spiritual essence, if you will—of nature’s importance has been sidelined. The Gulf Coast is not essential because of its commerce, its shielding of human interests from hurricanes, or its housing of endangered species—it is essential because it is beautiful, like all nature is beautiful, and by destroying it we are destroying ourselves, replacing it with something worse. Varisco’s work steers the conversation about the environment back toward what is deeply and profoundly at stake, and we should be grateful for it.

Editor's Note

“Shifting: Photographs by Michel Varisco” is on view through July 23, 2012, at the Ogden Museum of Southern Art (925 Camp Street) in New Orleans. The photographer will be signing books on July 12, 6 - 8 pm, and will give an artist talk July 21 at 2 pm, both at the Ogden.