Surviving Solitary

We’re sharing a collection of photographs by artists Maria Hinds and Matthew Thompson, who documented the belongings of Herman Wallace, who unjustly spent 41 years in solitary confinement.

Maria Hinds, Matthew Thompson, and Herman Wallace, Glasses, 2014. Courtesy the artists.

Editor's Note

In 2007, artist and designer Maria Hinds began working with the International Coalition to Free the Angola 3, an activist initiative fighting against injustice in the United States penal system. The group’s work centered on the release of Robert King, Herman Wallace, and Albert Woodfox, known as the Angola 3, from Louisiana State Penitentiary.

In the late 1960s, King, Wallace, and Woodfox were sent separately to the state prison, commonly called Angola (named after the former slave plantation upon whose land it sits and the ancestral home of that plantation’s slaves). They became acquainted with the efforts of the Black Panther Party in developing social programs and addressing police brutality in African-American communities. The party was critical of the ways the country’s prison system disproportionately and unjustly targets African-Americans. Woodfox petitioned for the creation of an Angola chapter of the party, and the group met to discuss revolutionary thought and books, including the work of W.E.B. Du Bois, Frantz Fanon, and Marcus Garvey, to name a few. In Angola, the men organized against segregation, corruption, and abuse, and in 1972, King, Wallace, and Woodfox were placed in solitary confinement, wrongfully charged in two different prison-murder cases—as retribution for their efforts and their association with the Panthers.

The Angola 3 maintained communication with each other despite their separation. Following years of legal battles supported by lawyers and activists outside the prison, the three men were released. King’s conviction was overturned in 2001 after he’d spent 29 years in solitary confinement. The state released Wallace on the basis of an unfair trial and humanitarian grounds in 2013 after 41 years in solitary; three days later he died of complications from liver cancer. Woodfox was granted his freedom in 2016, after 43 years in solitary confinement, the longest time any American has spent there.

While working with the Angola 3 Coalition, Hinds regularly wrote and visited Wallace and Woodfox in Angola and other state prisons where they were housed. In 2013, Wallace gave Hinds a collection of large duffel bags filled with personal items amassed over the years. Hinds began to see the value of the objects—ranging from a makeshift “kite,” used to send messages to other inmates, to socks modified to reduce abrasions from shackles—in affording rare insights into the lived experience of solitary confinement.

Hinds partnered with photographer Matthew Thompson to produce a series of photographs of Wallace’s belongings, and these works were shown recently in New Orleans in “Inside Out: Reflections on Incarceration in Louisiana,” a group exhibition organized by Level Artist Collective at Double Shotgun in the Bywater. The photographs were presented alongside anecdotes and quotes from Woodfox and Shareef Cousin, an exoneree who was housed in the same prison tier at Angola as Woodfox. This year Hinds donated a large number of Wallace’s items to the National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, DC.

To share this part of Wallace’s legacy, we’re presenting a selection of photographs from Hinds and Thompson’s series Surviving Solitary, along with captions they provided. We’re also sharing words from Woodfox and Cousin that appeared as wall texts in “Inside Out: Reflections on Incarceration in Louisiana.”

Maria Hinds, Matthew Thompson, and Herman Wallace, Cap, 2014. Courtesy the artists.

Herman paid other inmates to paint [Black] Panther logos on his clothes. Usually sergeants and other rank that worked the CCR [Closed Cell Restricted] tier didn’t mind, but once in a while what we called a “robocop,” security that stick exactly to the book, would tell him to get rid of it or would confiscate it and file a disciplinary report for contraband. This could result in either being sent to Camp J or losing store and/or yard privileges. It was important for Herman to be associated with or recognized as being one of the party members. The purpose of the party, contrary to negative media from the government, was to help change things, to help educate people. As members of the party, our purpose was to educate and to protect the community. Of course our community was the prison and in particular the tier we were living on.

Albert Woodfox

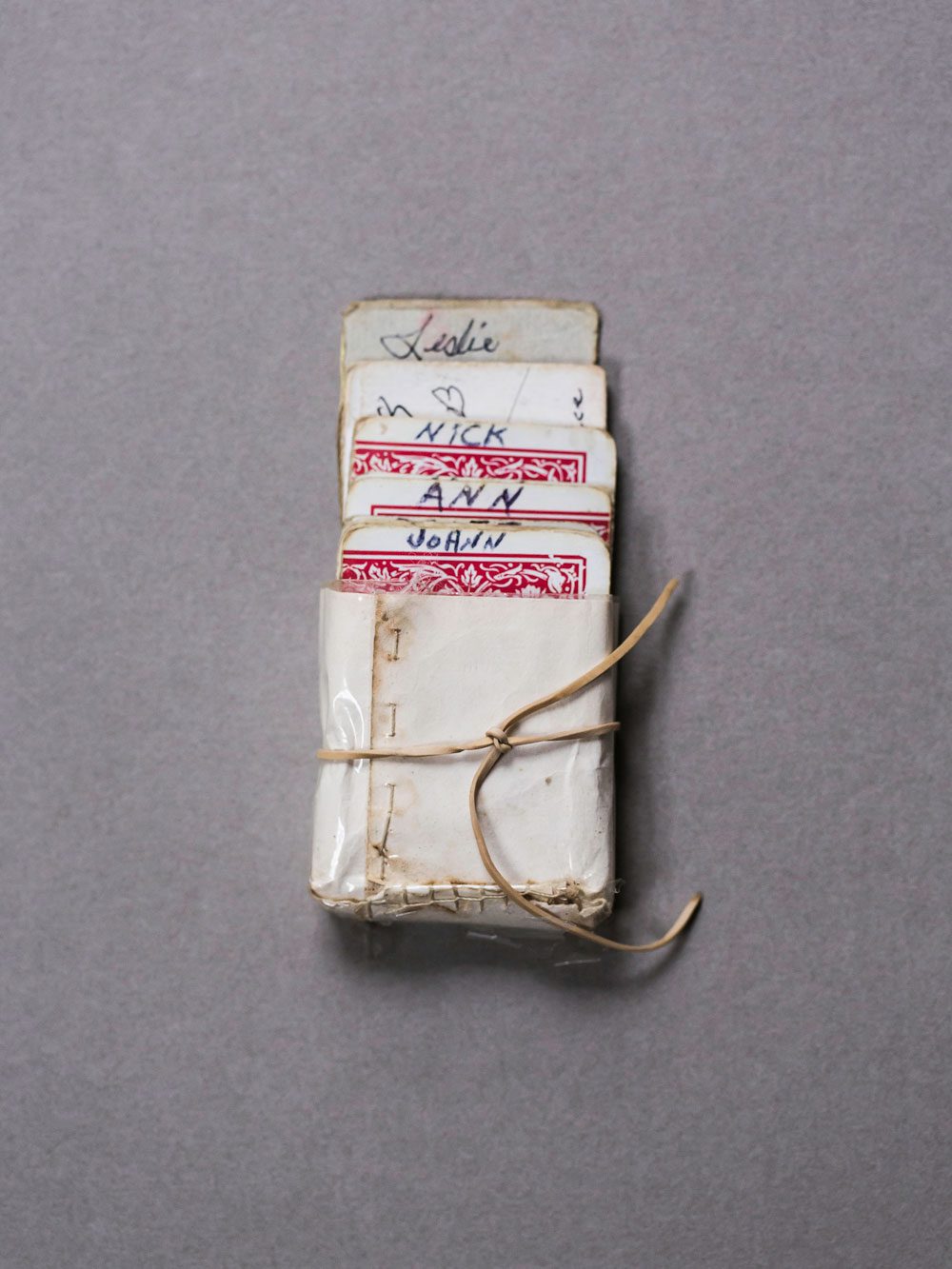

Maria Hinds, Matthew Thompson, and Herman Wallace, Address Book 2, 2014. Courtesy the artists.

A hand-stitched paper pouch houses an address book re-purposed from a deck of playing cards—wrapped with a cellophane layer from a cigarette pack. Names listed include Herman’s friends, family members, and attorneys.

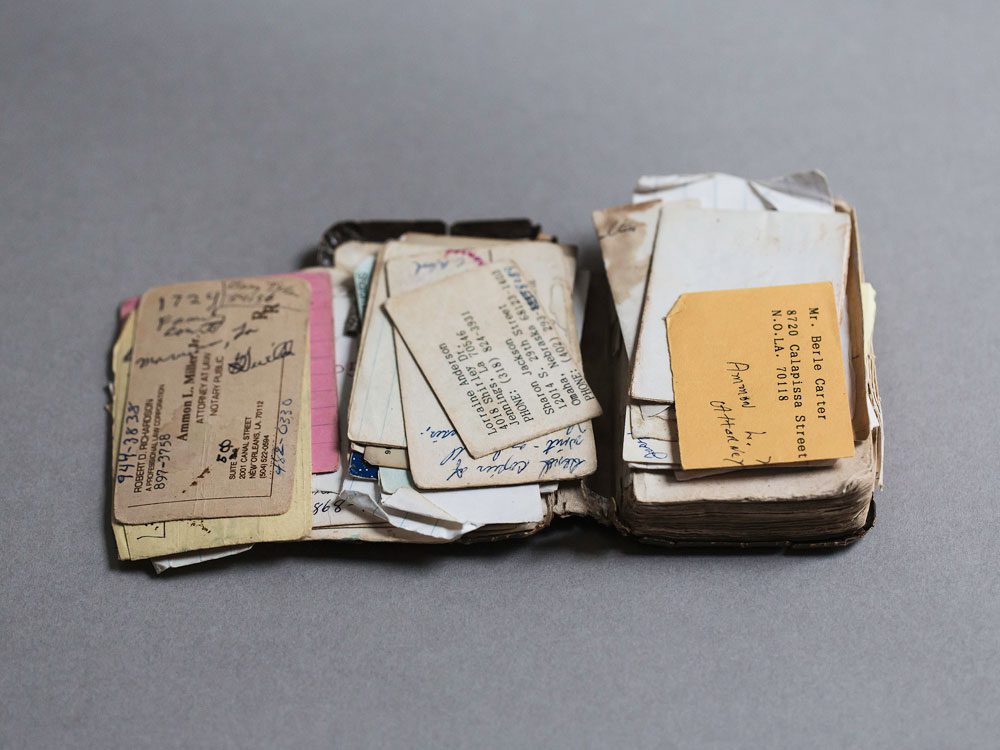

Maria Hinds, Matthew Thompson, and Herman Wallace, Address Book, 2014. Courtesy the artists.

In CCR and death row, every phone call and letter is monitored or censored by the administration. There is no privacy, particularly if you are a high-profile prisoner with pending law suits like the Angola 3. In prison, information is precious—phone numbers, addresses, and other lists are an important lifeline to the outside. When stuck in the cell with limited means, and no money for commissary, inmates write notes on any kind of piece of paper—necessity being the mother of invention, as they say. That experience affects your mentality for your whole life—you can never escape it.

Shareef Cousin

Maria Hinds, Matthew Thompson, and Herman Wallace, Clothing Label, 2014. Courtesy the artists.

Clothing supplied by Prison Enterprises, a division of the Department of Public Safety and Corrections that operates industry, agriculture, and service programs at eight correctional facilities throughout Louisiana.

Maria Hinds, Matthew Thompson, and Herman Wallace, Spoon, 2014. Courtesy the artists.

Herman elongated this plastic spoon so he could stir coffee. You can see this spoon is well worn and starting to melt.

Albert Woodfox

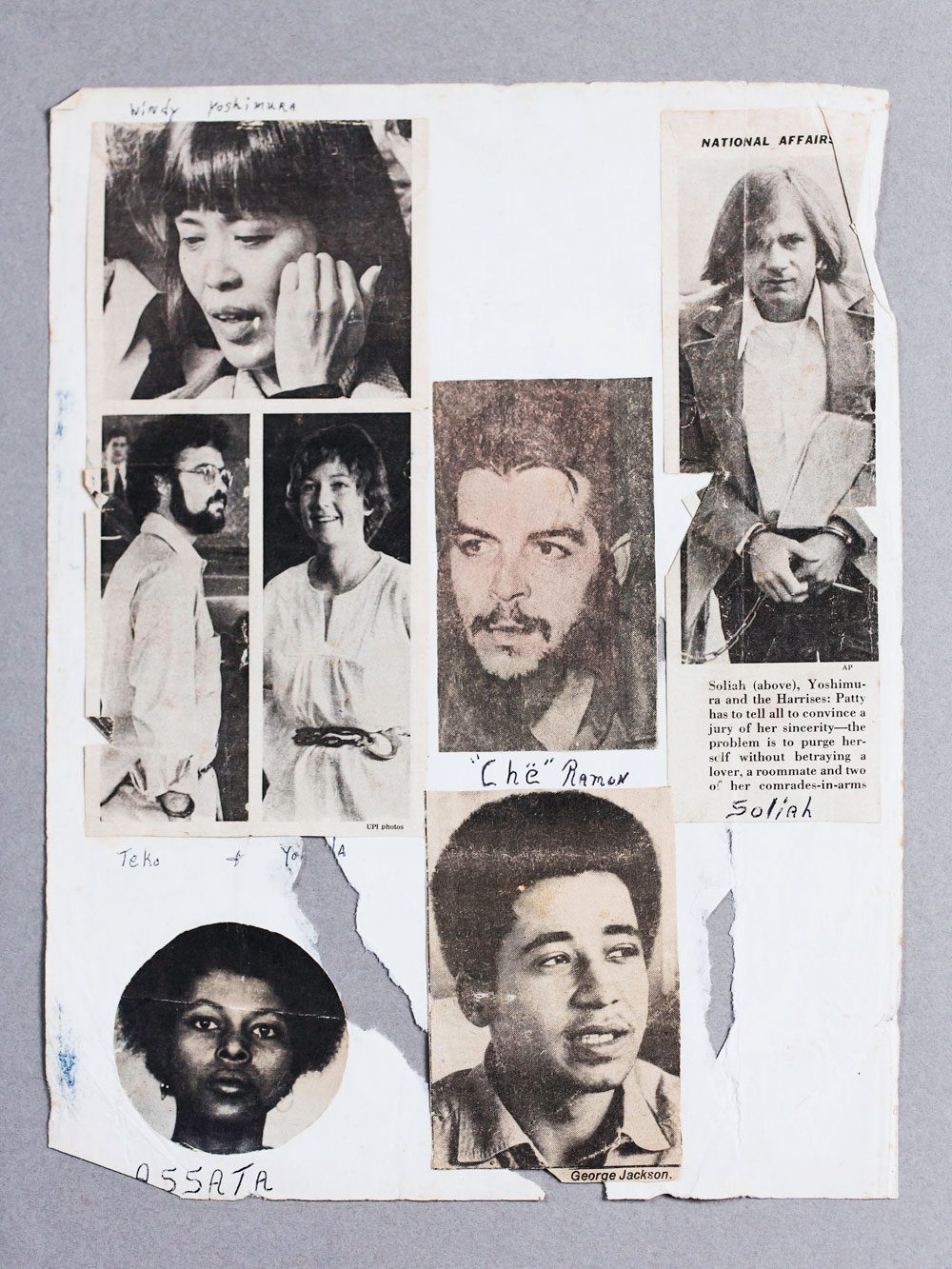

Maria Hinds, Matthew Thompson, and Herman Wallace, Scrapbook, 2014. Courtesy the artists.

Scrapbook page featuring Wendy Yoshimura; William “Teko” Harris, Emily “Yolanda” Harris, and Steven Soliah, all members of the Symbionese Liberation Army; Ché Guevara; and fellow Panthers Assata Shakur and George Jackson.

Maria Hinds, Matthew Thompson, and Herman Wallace, Chess Pieces, 2014. Courtesy the artists.

Herman was an excellent chess player—I actually think he could have qualified as a chess master. I’ve seen him play entire chess games from memory. These are factory-made pieces but there was a time when we were in isolation we used to take bars of soap and make chess pieces and chess boards. To play long-distance chess, you marked the chess board and played your pieces according to numbers. The tournament’s winner would win tobacco or some type of food item from the commissary—the prison term for [those snacks] is “zoozoo.”

Albert Woodfox

Maria Hinds, Matthew Thompson, and Herman Wallace, Socks, 2014. Courtesy the artists.

Thirty or forty years of forcibly wearing ankle shackles every time you leave the tier causes wear and tear on the body. For survival you have to create something to self-protect. Men usually ask the guard to put the leg irons outside of the jeans and some guards will do it. Some will refuse.

To get to CCR means you have been through the disciplinary process, been to Camp J and been beaten. The path to CCR is one of abuse and torture—for some men it is a destination they will never leave. This item, again, represents torture.

Shareef Cousin

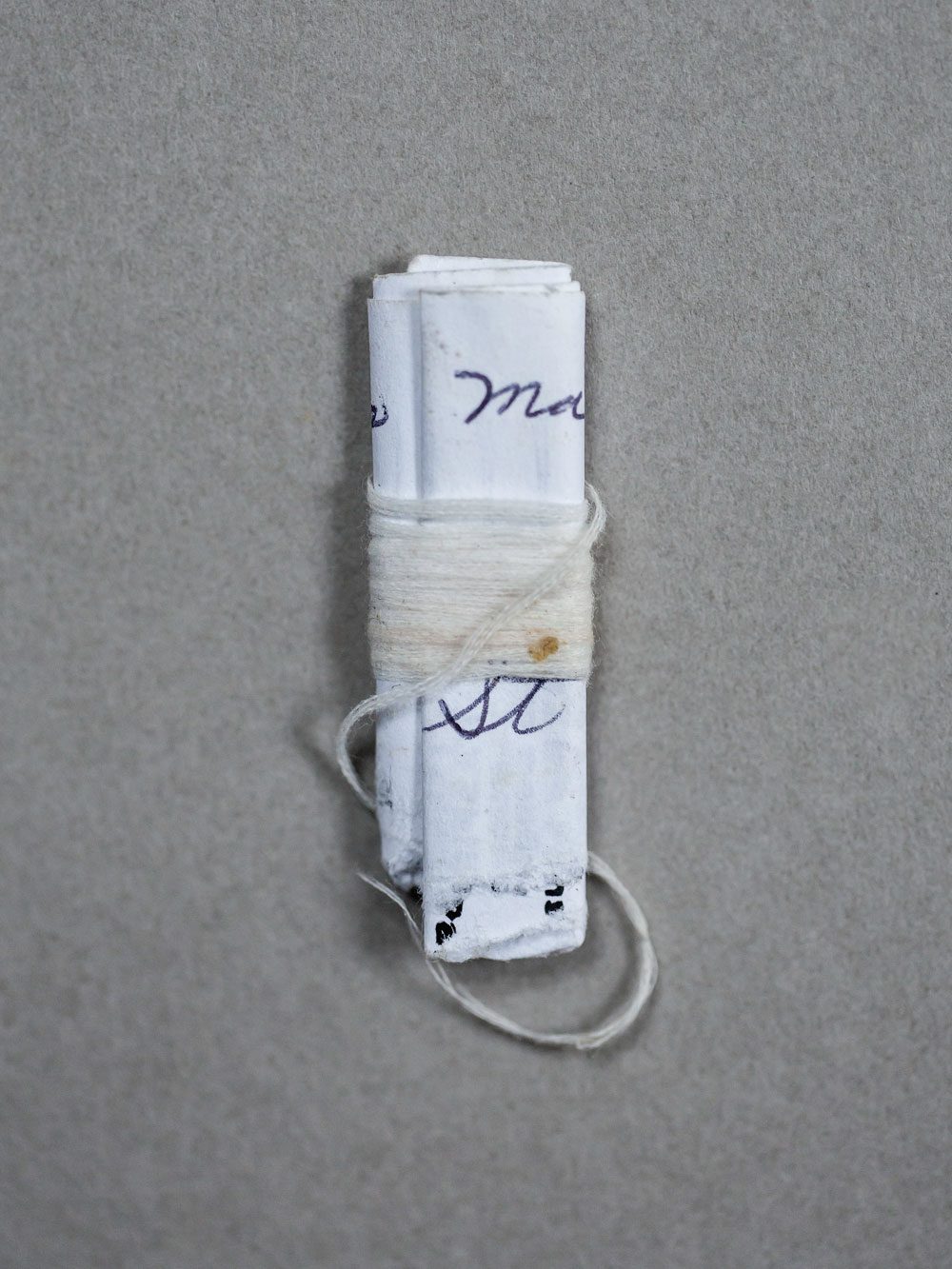

Maria Hinds, Matthew Thompson, and Herman Wallace, Kite, 2014. Courtesy the artists.

“Kites” are commonly used on the CCR tier to relay a message from one inmate to another. Wrapped and bound with string, a kite can be easily retrieved if it does not reach its intended recipient. The unraveled kite revealed the following note in Herman’s handwriting: “Same Sex Marriage, Maryland, Washington St[ate].”

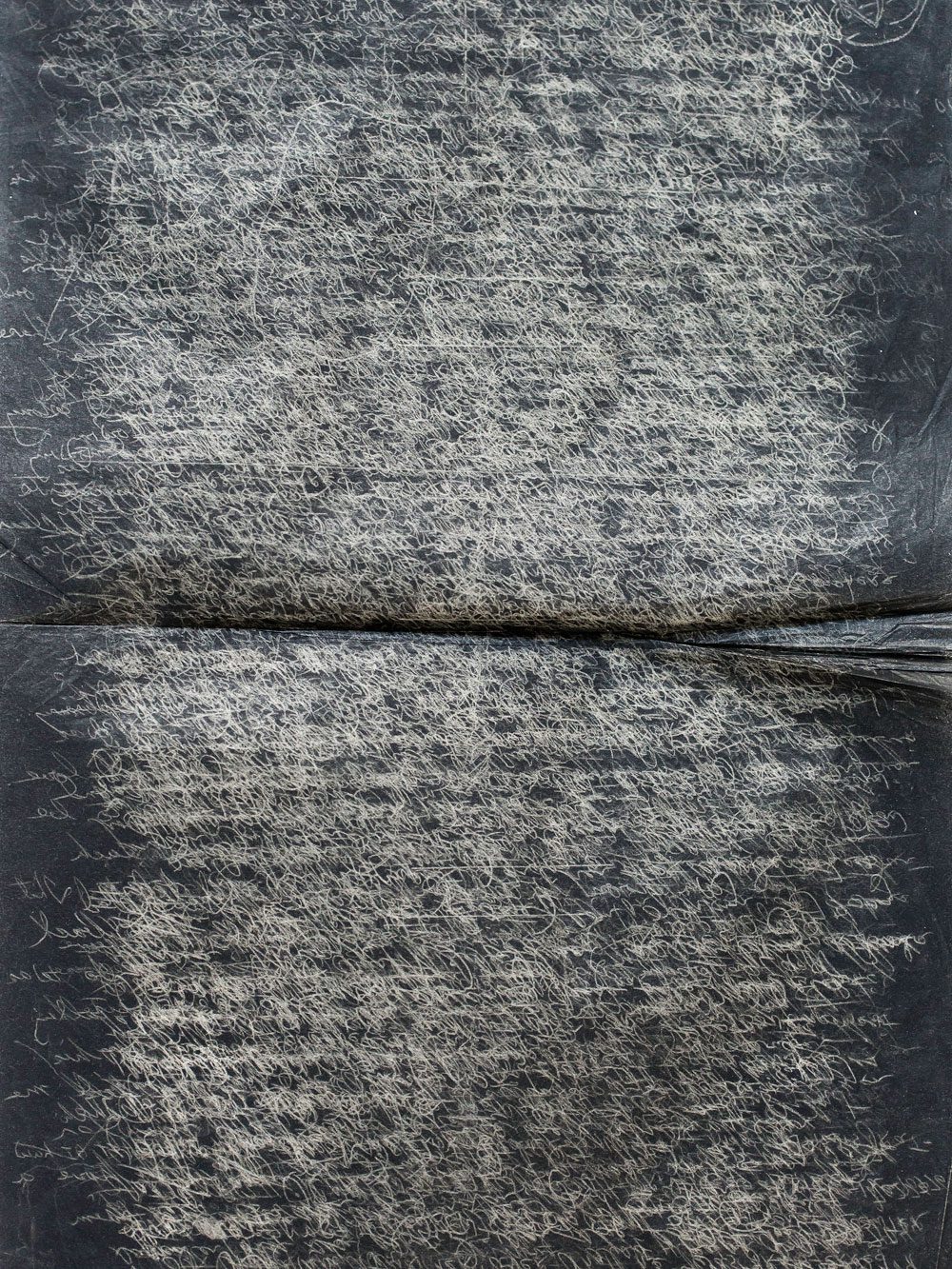

Maria Hinds, Matthew Thompson, and Herman Wallace, Carbon Paper, 2014. Courtesy the artists.

Herman used carbon paper to duplicate hand-written letters and legal documents. CCR inmates were limited in the amount of items they could have in their cell so as you can see, this particular sheet has been used many times over. You can imagine how problematic it would be for pro se litigants to have to hand write duplicate copies of their lengthy writs and legal documents, of which the courts often require three copies or more.

Albert Woodfox

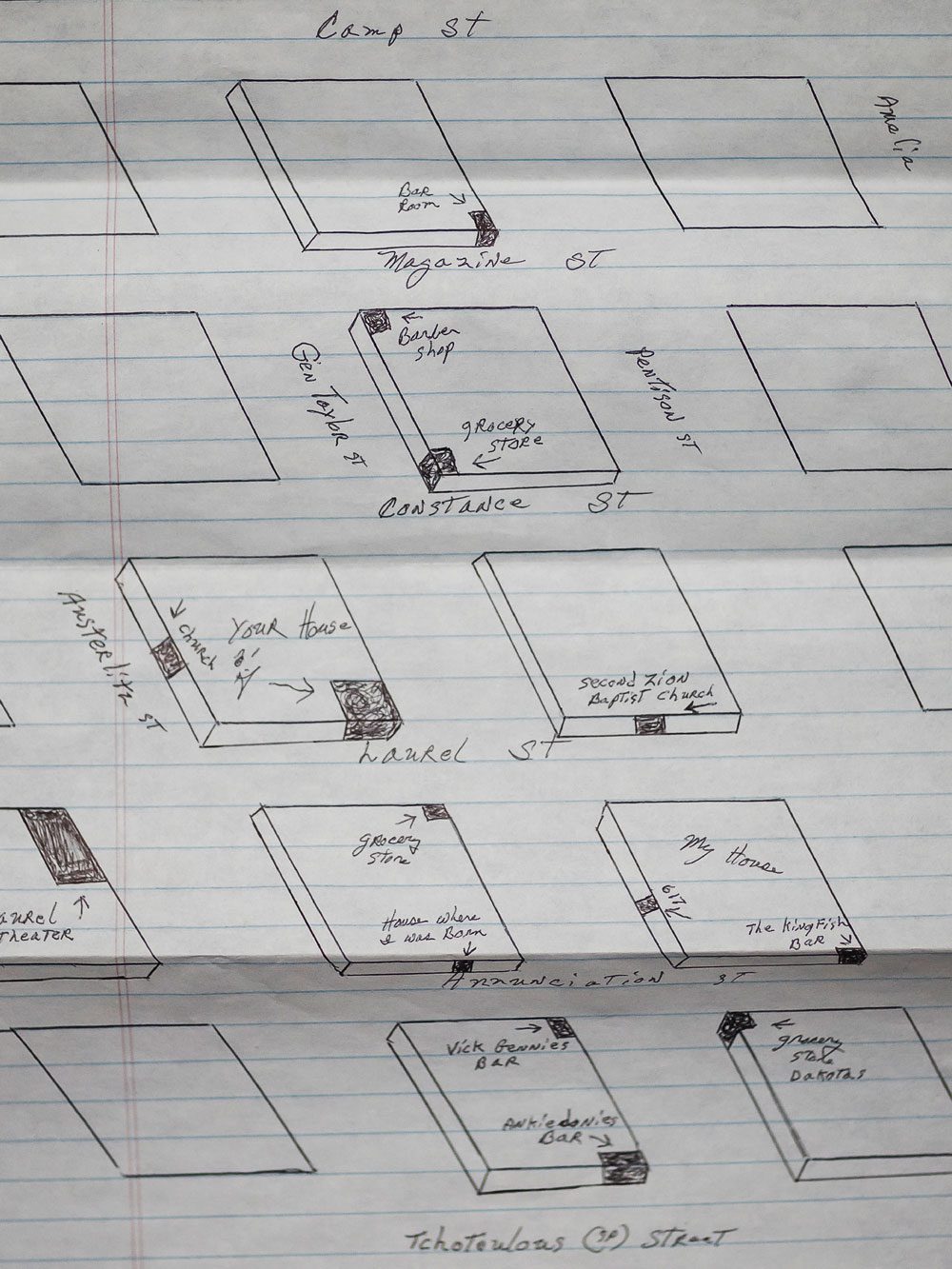

Maria Hinds, Matthew Thompson, and Herman Wallace, 13th Ward Map, 2014. Courtesy the artists.

Vividly recalling the order and geography of New Orleans streets was a source of pride and amusement for Herman. He drew this map of the Uptown neighborhood where he was raised, marking local houses and businesses for a friend who lived on General Taylor Street, one block from his childhood home. Many of these homes and businesses either no longer exist or have relocated during the 46 years since Herman’s incarceration.

Editor's Note

“Inside Out: Reflections on Incarceration in Louisiana” was on view April 14–May 6, 2018, at Double Shotgun (3024–26 St. Claude Avenue) in New Orleans.