Get on Our Level: The Founding of Level Artist Collective

Ashley L. Voss talks to the five members of Level Artist Collective and looks at how their work has changed since they began working together.

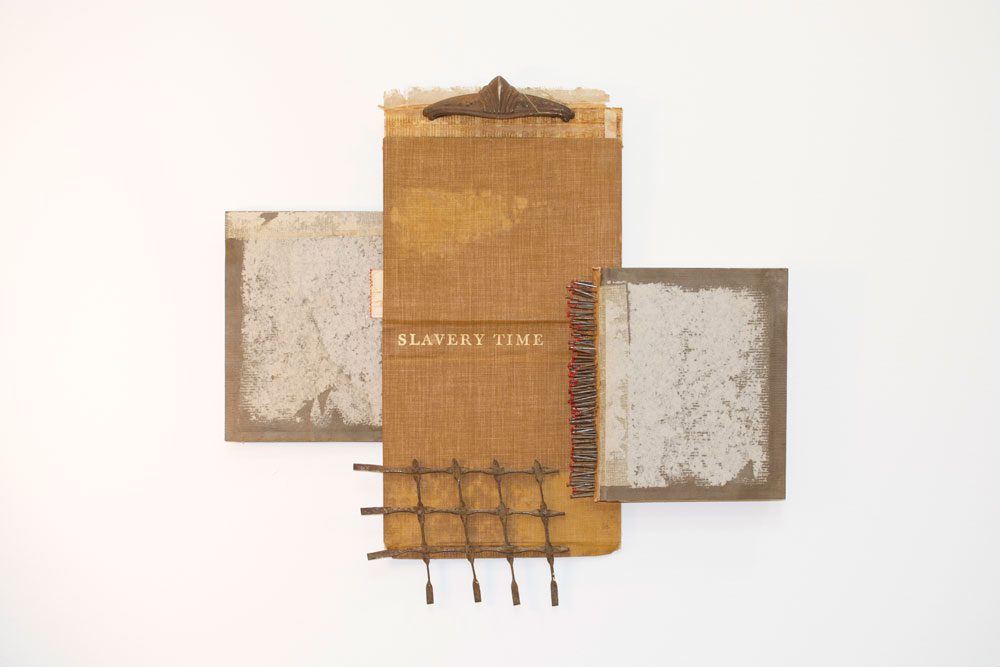

Ana Hernandez, Deconstructing Façades and the Fallacies within Narratives of the Past, Present, and Future, 2016. Deconstructed book, metal fence, metal handle, and nails on wood panel. Courtesy the artist.

In March 2016, I rode an elevator to the third floor of 338 Baronne Street, unaware of the invigorating scene I was about to encounter. As the doors slid open, a bustling crowd of artists mingled throughout makeshift studios. Dismantled pallets received new lives as walls, their skeletal structures repurposed to reinforce the effort of art-making. The combined charisma of the Level Artist Collective greeted me at the door, as they welcomed me to their first open-studio event. I toured the studio spaces with the five artists, and, as they spoke about each other’s work, I was enchanted by their genuine camaraderie and mutual respect. I learned that found materials not only formed the framework of the studio spaces, but also were evident in the artwork on view. In a glance, I saw mattress springs straining beneath the weight of glass panes and stacked televisions seemingly silenced by a rainbow of paint.

Level Artist Collective—comprised of New Orleans-based artists Ana Hernandez, Horton Humble, John Isiah Walton, Rontherin Ratliff, and Carl Joe Williams—was formed in October 2015 to support each other’s artistic practices as fellow contemporary artists and friends. In July of that year, Young Aspirations Young Artists (YAYA) had informed local arts organizations about affordable art studios on Baronne Street in the heart of New Orleans’ Central Business District. YAYA had moved into this space in 2008 with the help of board member and photographer Jim Belfon. While searching for a studio of his own, Belfon found the space and thought it would be perfect for YAYA’s programming. “The space was great for light and ideal for downtown access,” says Rontherin Ratliff, who was the creative director of YAYA at the time. (He worked there from August 2008 to May 2015.)

Rontherin Ratliff, Engrossed, 2015. Glass, remnants from past work, and marble. Courtesy the artist.

By fall 2014, when YAYA began construction on their new arts campus in Central City, this third-floor studio was left vacant, and it remained that way for seven months until the organization was able to reconsider its possibilities. With the desire to continue using that space to support local artists, YAYA made the space available as studios. Ratliff offered to work with YAYA to kickstart and manage the studios, and his first task was to transform the open space into individual units to accommodate different artists.

As each artist arrived after Ratliff—Humble, Hernandez, Walton, and finally Williams—an additional room was built. Hernandez remembers, “It was an empty floor plan so we had to find a way to create studio spaces for each other. We drove around collecting all these pallets to divide the space.” Using found wooden pallets, Ratliff built partitions starting from the window on the far side of the room. This lineup of three painters and two sculptors each had their own completed studios within two weeks, and they joked that the rooms gradually became smaller the further they were from the window where Ratliff had started. By August 2015, everyone was settled in.

In New Orleans, a small town masquerading as a big city, these artists were already acquainted. Williams and Humble had met at the age of 15 while attending the New Orleans Center for Creative Arts. Their friendship fell to the wayside when Williams went to Atlanta for college but was quickly rekindled at a party 16 years later. Ratliff—who Williams knew from the Joan Mitchell Center’s Local Artist Studio Program pilot—and Hernandez—who had befriended Ratliff after bringing her students from the University of California, Berkeley, to YAYA during a trip to New Orleans in 2008—were also at the party. Walton came into the mix at a reception for an exhibition at the Ogden Museum of Southern Art.

Despite these previous connections, moving into the studio space at 338 Baronne was the first time the artists worked alongside each other. “You learn so much about a person by working with them,” says Hernandez, “One thing you begin to notice are people’s work habits.” Before long, it was well known among the group that Hernandez enjoys maintaining a clean work environment, that Walton has a tendency to postpone his creative process until deadlines are fast approaching, and that Williams finds artistic solutions amidst chaos. Walton recalls, “At certain points in the night you could hear a machine going off from Rontherin cutting wood. But in the daytime he was researching and doing computer work. Then you have Horton who would be there everyday until one o’clock in the morning. He would take walks all the time for inspiration.”

Carl Joe Williams, Irony of a Black Police Man, 2016. Mixed media with original music and video of police shootings. Courtesy the artist.

The artists began to develop friendships with one another outside of the studio and attend one another’s receptions and artist talks. “We were already meeting each other at the shows, but then we just started leaving the studio together to head to the shows. We started being a band in a sense, but organic. You’re not really seeing it at the time and I think that’s what makes it beautiful,” said Humble. Gia Hamilton, Director of the Joan Mitchell Center (JMC), was the first to refer to the group as a “collective” in a conversation with other artists at an event hosted by the Contemporary Arts Center—and it stuck. Soon, artists and arts professionals across the city had embraced them as such. Realizing the power of their presence, the five artists decided it was time to officially name themselves, before someone else did.

In October 2015, after considerable brainstorming, Level Artist Collective was born (“Uranium” was their second choice). They settled on “Level” for a variety of reasons: the five letters representing each of the artists involved, their third-floor studio space, the harmonious connotations associated with notions of balance, and the mutual motivation to continually challenge themselves.

With the drive to perform at a “higher level,” these artists also revel in drawing connections between the fine-art world and work created by artists without degrees or other formal training. As Humble attests, “I don’t have the pedigree, but I definitely have the desire to be a part of that conversation.” This aspiration is parallel to their aim to strengthen the presence of people of color in contemporary art. “When hearing about a collective of Southern artists, folk art is usually assumed,” said Williams, “We want to change that.”

This “collective” label that came to define their friendship took some adjusting to. “It’s funny to call yourself a collective when you only have five people. You’re not really collecting anybody at this time. You’re more of a group, like the Jackson 5 or something,” said Humble. However, their new name granted them cachet when applying for grants and various funding opportunities. “I learned there is strength in groups. We were all artists before, but once people saw us supporting each other and showing up to each other’s events in the community, there was a response,” said Hernandez, “I think people took us more seriously and began giving us more opportunities.”

Horton Humble with his work Race, 2017. Oil and pencil on canvas. Courtesy the artist.

The name also worked in their favor as an increasing number of collectors and curators began scheduling studio visits, with professional acquaintances especially willing to survey the work of five artists in just one walk-through. As more meetings were scheduled, the members engaged in roles beyond that of the artist and became representatives and even salespeople for each other’s works. “It turned out to be a plus for everybody because when I had a studio visit with a curator, I would randomly show everybody’s work quick before heading to my studio. I think we all did that to each other,” said Williams. To streamline the process of discussing another artist’s work, they printed a booklet to distribute that explained everyone’s artistic processes. “It forced us, as artists, to move forward. One of the things we struggle with is getting language together about the work,” said Ratliff, “This way, we were able to help each other out.”

Each member already had a personal history of patrons and supporters who helped guide their careers up to this point. Their networks were also expanded by each member’s associations with different arts organizations in New Orleans. “The cool thing about the group is that everybody is a part of different art factions in the city. For example, I’m a member of The Front and Rontherin is affiliated with Antenna, YAYA, and the JMC—and some of these people don’t even meet up! Then here we are having all these people from the Julia Street and St. Claude scenes coming to visit our space. We’re bringing it all together,” said Walton.

As awareness about the Level Artist Collective grew, the members each unofficially adopted various roles to maintain a balance in the newfound structure based on individual strengths and weaknesses. Ratliff reminds everyone about upcoming deadlines, in addition to upholding the general maintenance of the studio space. Hernandez and Humble manage the collective’s online presence and search for discarded materials and objects for the group to use in their creative practice, while Walton and Williams contact venues for exhibition purposes and curate any shows the group secures. “It’s about support and accountability,” Ratliff said.

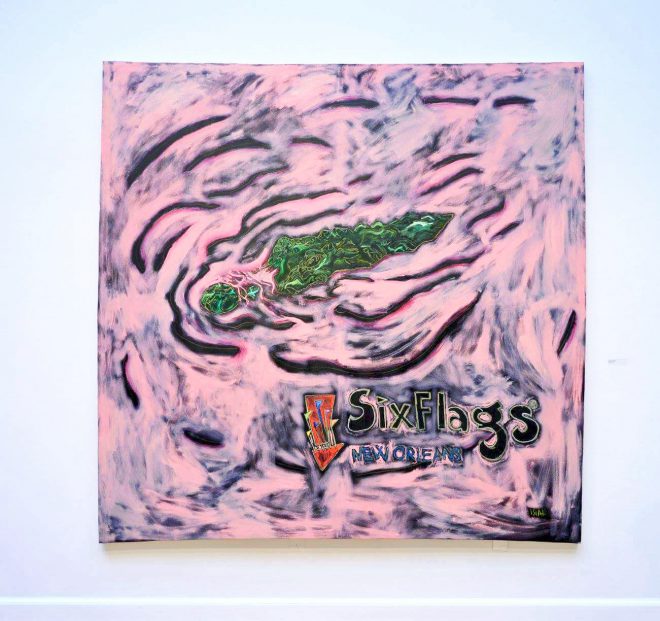

John Isiah Walton, Pink Gator, 2017. Oil on canvas. Courtesy the artist.

Nearing a year into the their time in YAYA’s studio spaces, contractors and architects began accessing the building while they were working—an ill omen. The members were aware their lease was ending but were also hopeful the landlord and YAYA would extend their contract for studio space. However, with the recent condo developments and increasing property value in the CBD, the final decision didn’t come as much of a surprise, and Level Artist Collective was asked to vacate the space after one year on Baronne Street.

As of March of this year, the members have exhibited twice as a collective. Their first exhibition was at Antenna in late 2015. This debut, only months after their formation, not only functioned to display the artists’ individual works but also brought other artist friends, predominantly those who grew up in New Orleans, to the fore. Their second exhibition, at Tulane University’s Carroll Gallery in 2017 after having lost their shared studio space on Baronne, was more cohesive and demonstrated the influence they have had on one another’s artistic practices. Having worked alongside each other, the artists developed a dialogue around identifying as artists of color who are making work to reflect their individual and collective experiences of identity, race, and class—and how these issues are subject to the context of place and time.

Despite their relatively brief residency at 338 Baronne, the artists maintain a positive attitude about the overall experience and are continuing to build on the possibilities it opened up. “I think it’s all about empowering ourselves right now, if we can find a studio space together we would be fine. But right now it’s all about finding that comfortable spot as artists—following your yellow brick road,” said Williams. What originated from the desire for affordable studio space evolved into a support system of like-minded artists driven by the same purpose: to put their work—and New Orleans—on the map.