A Dissonance of Parts and People: Publishing from the Provinces

James McAnally considers the importance of publishing arts writing outside of major metropolitan areas like New York and Los Angeles.

Press Press Young Scholars hosts publishing, writing, and art workshops with refugee youth in all-immigrant & -refugee spaces. The project is founded by Baltimore-based publisher Press Press in partnership with Baltimore City Community College’s Refugee Youth Project.

This Midwest, a dissonance of parts and people, we are a consonance of Towns…we overlabor; our outlook never really urban, never rural either, we enlarge and linger at the same time….

William Gass, “Politics,” In the Heart of the Heart of the Country

Art outside the center, off the given grids, grows uneven in its distance. We are a dissonance of parts and people, a consonance of communities; we overlabor as a rule. In the heart of the heart of the provinces, the place of the artist is unstable, the art world a mirage with no clear entrance or exit. We can say “we” as a start even when we are states away.

A longstanding game is to interpret artistic tendencies in specific cities in some kind of constellation, pitting the outposts against one another, and all against the center. The relative privileges of low rent and easy exhibitions, quick acclaim and soft connections, and the big fish-small pool languor has remained more or less unchanged over the decades. The art world highlights these hierarchies of geography, fixing the artist in relation to place as one criteria among many that establishes value.

Writing from outside of art centers, many assume we live in the margins—some incomplete version of the art world that only finds definition in relation to the center. What are these provincial aesthetics? What does it mean to fix an artist in a place, and how is it suggestive of anything on its own? Or to turn the questions around, what do we see differently when we look from these margins? Could we critique the province of the contemporary art markets and its attendant institutions from here, as if they are the deviation, the outer lands of the arts? Who is correct in this? The one who refuses the other? We are both correct, irreconcilable. We are both incorrect, unrealizable.

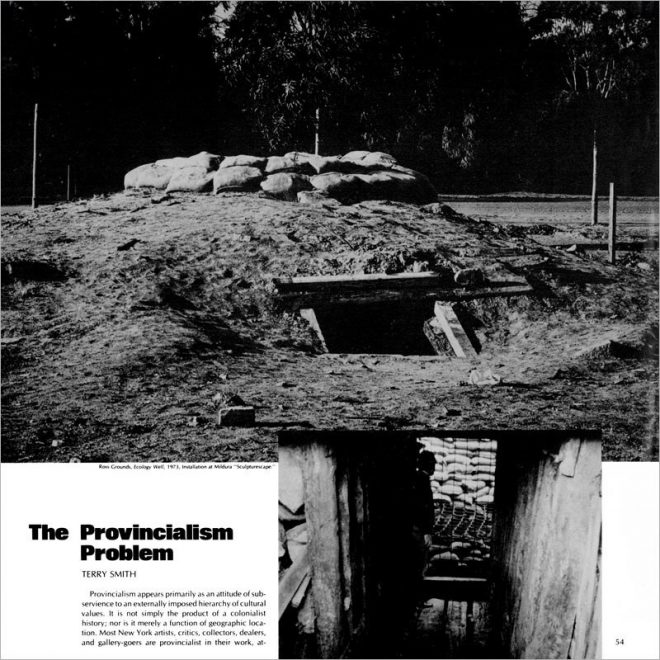

In a far-reaching, unsurpassed analysis, Terry Smith considered “The Provincialism Problem” in a 1974 Artforum essay, assessing the artist’s place in relation to the center as a system of perpetual alienation. As he puts it, provincialism is precisely “an attitude of subservience to an externally imposed hierarchy of cultural values.” This analysis has proved perennial as the authority of the art world always seems to come from elsewhere, unlocalizable but nonetheless impossible to trespass. In Smith’s view, the commercial and institutional art world typified by New York is the ultimate province, as cloistered and limited as any other locale with its own codes and blindnesses rendering it unable to see the expansiveness of artistic practices that don’t cohere to its prescribed codes.

Provincialism for Smith is defined less in relation to geography and more in relation to power. It assumes an inscription into one’s context or container of identity as defined from outside. One can think here of the marginalization often meant in terms such as “rural artist” or “regional publication” or any other description meant to limit how one’s work is to be understood from an outside view. Though externally imposed, these hierarchies are internally adopted and reaffirmed in the ways we tend to conceive of the art world as a series of ascensions towards recognition or acclaim. Art’s value, in this view, isn’t immanent—it is always determined elsewhere. It is negotiated as an industry of recognition and circulation, capital and canons, rather than the inherent value of expression, experimentation, and creation we wish to claim as its central power.

Terry Smith, “The Provincialism Problem,” published in Artforum, September 1974, Vol. 13, No. 1.

Art publishing is often complicit to these conditions, tending to celebrate the orientation of art around existing hierarchies of power. However, regional publishing, marginal publishing, oppositional publishing are possible places for the redefinition of art’s value outside of these hierarchies. They can engage artistic practice on other terms: contextual, conceptual, site-responsive, embedded in place, community-centric, communal, counter, illegible to an outside. They carry an ability to trespass, to refuse. They make possible shared self-definition, while also expanding and complicating assumed narratives. They are places in which sustained argument may happen with a multiplicity of voices. They document and archive what is otherwise potentially unseen to an outside, carrying that work forward in time. They can be contradictory (and are almost necessarily so), in this way making sure a place and its practice contains multiple meanings. In short, they refuse the provinces that the center attempts to propose.

Smith’s focus was primarily on Australian art communities, notably pre-Internet, but the problem he described persists for all our present provinces: The more one wishes to appear in dialogue with the center, the more likely one will be a step behind. The extent to which one embraces one’s place itself on its own terms, the more likely a new form will emerge. A dismissal of the contingencies of the center is necessary for an escape. This is the most—and least—risky proposition for the artist in this dissonance of parts and people others term the margins. The value of a regional publication is a means of pushing the nuances of artistic practices rooted in place ahead. At their best, they amplify the idiosyncrasies and insider arguments in communities into something approaching a discourse. They may deeply define a place on its own terms, documenting that argument and disseminating it outward through an unpredictable public.

Temporary Art Review, the online publication I co-founded with Sarrita Hunn, started as a multi-modal publication that was originally meant to be a series of regional outlets all connected through our central platform. The scale never quite took and became unmanageable for our own volunteer labors and we quickly shifted to a national (and, later, international) platform aimed at connecting contemporary art writing about artist-centric and alternative practices among disparate communities. Throughout our history, however, we’ve been interested in what happens when regional concerns connect outside of the center. It is an unresolved and perpetually incomplete question, but one that remains as a challenge for how to export regional discourse, both for sustainability and learning, circulation and criticality.

As Smith says, “irresolutions such as these pervade the culture. Artists live uneasily within it. None can feel part of a community large enough, diverse enough, to be self-sustaining—an illusion often given by New York.” He goes on, proposing that “as long as strong metropolitan centers like New York continue to define the state of play, and other centers continue to accept the rules of the game, all the other centers will be provincial, ipso facto. As the situation stands, the provincial artist cannot choose not to be provincial.” (emphasis mine) The process that sifts these definitions is a structural hierarchy built up by an economy and a self-reproducing social strata, and maintained by mass acquiescence to its assumptions. The question, then, is how do we embrace new rules? Without a concentrated field that encompasses work outside of the centers as sites of emergence and possibility, we are necessarily accepting a provincial position.

Beyond Alternatives supports artist-led projects and organizing happening outside of large metropolitan areas. Image: Beyond Alternatives Symposium in Urbana/Champaign, Illinois, on April 6–7, 2018.

What may it mean then to publish from other provinces? To the extent that other art worlds, emergent practices, and unpredictable constellations of art’s relationship to society are present in these provinces, then publishing of and from there becomes critical to a formation of other canons, of archives oriented towards both expanded presents and expanded futures. The act of public-making inherent to publishing has the potential to draft new territories, whose borders we define, whose shared values we articulate.

Publishing, as in artistic practices, thrives best when connected to place and communities. These communities are not self-sustaining and any single artist or publication will necessarily be adrift without one another. We must refuse the rules. We must also invent new means of circulation that connect counterpublics into a counterpower to the center. Towards a new definition, an accelerated provincialism: Our avant-garde is circular—we are at the forefront only when we are at the edges. As we push our boundaries outward, we enlarge the space for all. The further from the center we are, the more likely we will be at an expansive new border.

The publisher, no matter how small or “marginal,” owns the means of its own production and distribution. It chooses what it speaks to, how it defines itself and its place. It is its own micro-site of organizing. It is an essential component of any self-sustaining arts ecosystem because it is not focused on the self, but the collective. Publications reach outward. They wish to live collectively held, drafting new publics, connecting disparate threads. The regional publication is important, but it gains an ineffable power as it connects with other publishers and other publics.

I’m writing here for a publication that has held this space for over seven years in New Orleans. Its present form is closing, but its archive will continue making this argument ahead if we let it. In its close, other possibilities for self-definition through publication remain open for others. New zines, xeroxes, blogs, books, and more will be taken up in the months and years to follow. I write from other provinces, ones with names like St. Louis, or Temporary Art Review, or alternative spaces, or the Midwest, but we have shared some space of publication for several years, weaving towards other art worlds. Though this phase of collaboration closes, we will still linger and enlarge: a dissonance of parts and people, a consonance of concept.

Editor's Note

A portion of this text is adapted from an essay for the Oklahoma Visual Arts Coalition’s Art 365 catalogue, published in 2017.