Space and Silence: An Interview with Yumi Sakugawa

As part of our series exploring issues of wellness and healing, Ryan Lee Wong talks to Los Angeles-based illustrator Yumi Sakugawa about her new book promoting healthy habits and her strategies for self-care.

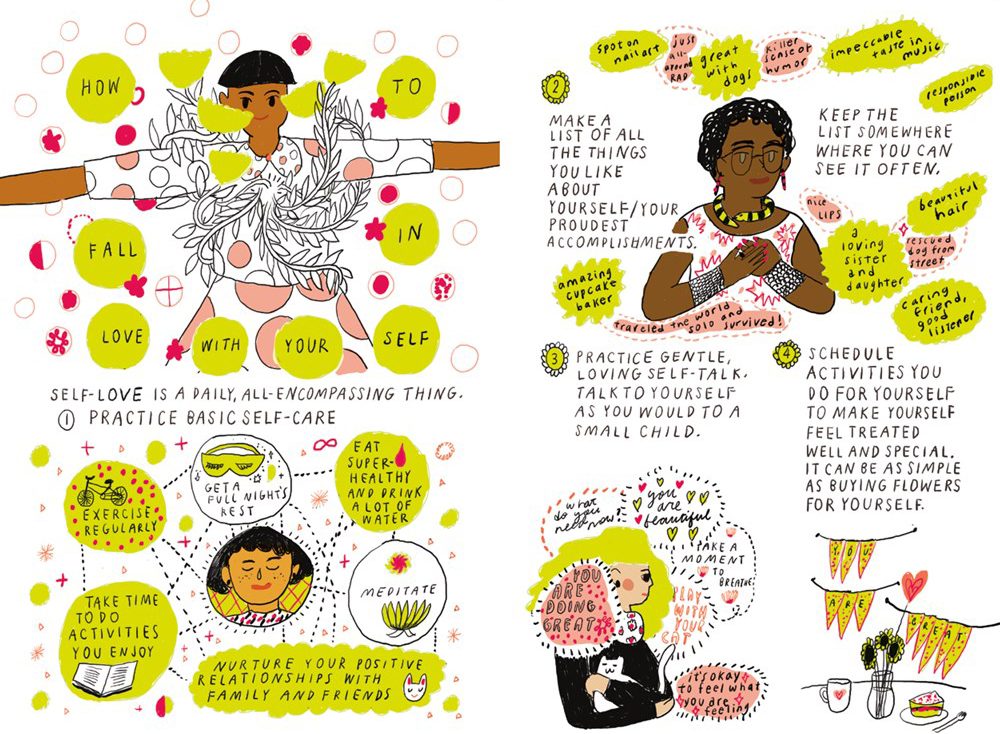

A spread from Yumi Sakugawa’s The Little Book of Life Hacks (2017), published by St. Martin’s Press.

Ryan Lee Wong: We’re holding this interview weeks into an incredibly painful time, when families are being separated at borders and democratic processes are being dismantled. How are you practicing care for yourself these days?

Yumi Sakugawa: Around the time Trump was elected, I was beginning to experience issues I hadn’t experienced before. I had my first panic attack the night after the election. I was also not able to use my dominant hand the last few months, along with other health issues I didn’t know the origin of.

One practice that has always helped me is consistent meditation. For twenty minutes when I wake up each day, I’m sitting in mindful silence, and for an hour before I go to bed I’m not online. Honoring that sacred space, when you’re not checking the news, is really important so you aren’t overwhelmed with all this information.

Even simple things like eating healthy are so important for me—because of my health issues, I’ve almost been forced to do this. But even for people who don’t have health problems, you’re going to need more physical and mental energy, especially in such a scary, turbulent time, when voice and action are needed. Those things all require energy: whether it’s going to a march or processing complicated information or having the immune system to handle stress and anxiety.

One other thing: Community and relations are really important—to process things together. I’ve been making a conscious effort to go to more community events, connecting with people on a day-to-day, face-to-face level.

RLW: I’m interested in this emphasis on the everyday in your forthcoming book, The Little Book of Life Hacks, where you offer DIY projects, beauty tips, and fitness routines. Where did the idea come from?

YS: I used to work for a website called Wonder How To, where I created illustrations on “life hacks”—for example, different ways to use baking soda, or how to take wrinkles out of clothes without an iron. I did that for almost four years. It was my literary agent’s idea to bring that all together in a book. I think it was an intimidating idea—I don’t consider myself a lifestyle expert.

It was an interesting challenge—especially as a woman of color, growing up with lifestyle magazines that didn’t have Asian-American voices—to create an illustrated world where women of different colors and sizes are represented. I was able to bring that perspective, even if I’m not a Pinterest-perfect lifestyle person.

RLW: I, and many of my friends, have been struggling lately to hold onto a sense of groundedness. So many of the practices in your book are grounded in the physical—home and body. How do you balance that with the digital—social media and news?

YS: I think it’s really important to set limits on how much you’re taking in news. I like to time it: I’ll set aside maybe thirty minutes in the morning, and maybe another thirty minutes or an hour in the evening. I subscribe to a few newsletters with action items, calling senators or signing petitions. Even if it’s a small act, it’s important to have a sense of agency.

Also, acknowledge that you can only do so much every day. A lot of news is sensational in nature, in addition to bringing information. It’s not always helpful to be in a constant state of reaction. If a lot of these problems are going to be solved, we need long-term planners who aren’t online every hour, who maybe need an offline retreat somewhere, to have in-depth and intricate systems to tackle these complicated problems.

Another thing is challenging myself to read books, whether on immigration or civil rights movements. I feel people need to be reading books in addition to CNN, or Huffington Post, or Twitter. It’s a way of feeling you’re doing something without these sensational sound bites. I started reading Angela Davis’ collection, Freedom Is a Constant Struggle, and also [Mike Davis and Justin Akers Chacón’s] No One Is Illegal. And in general, I always go back to A New Earth by Eckhart Tolle, which is super new agey, but being in the present moment is sometimes the most we can do when the future is so uncertain.

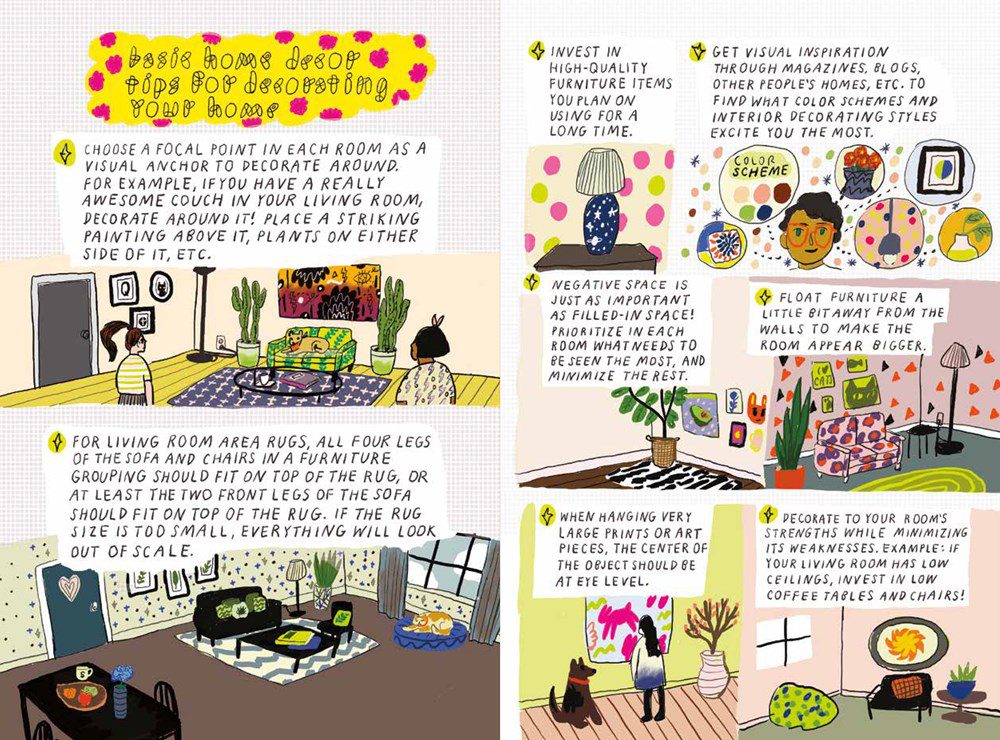

A spread from Yumi Sakugawa’s The Little Book of Life Hacks (2017), published by St. Martin’s Press.

RLW: Switching over to your artistic process: The way each character in your work looks conveys something about their role—there are demons with tentacles and multiple eyes, as well as gentle foxes. Where do these creatures come from?

YS: I almost never want to draw myself as the protagonist. Even in my autobiographical comics, I draw myself as a bunny character. By making them not human, they are relatable to all humans. If the characters looked like me, it pins the experience to a certain demographic. Even if they’re me, I like to make them blobby, amorphous, asexual. A weird monster with eyes and tentacles and horns is a demon version of me.

RLW: I’m interested in your use of space. In one panel, you’ll have a minimalist scene of a lotus blossom in water, and then an incredibly detailed amalgamation of seeds, plants, people, and animals on the next. Are those compositions intuitive? Are they planned?

YS: It’s a combination. One thing a visiting instructor [at University of California Los Angeles] told us was, it’s important to have space in your drawing field. That gives room for the viewer to place more of him or herself into the experience. Those are the kinds of artworks and writings that I resonate with the most—where there’s a sense of space. Whether it’s auditory, like silence, or visual, like the minimalism of Hokusai’s line work. When you give the reader space, they have breathing room for their own experiences to come up.

With the books I make, it’s never about telling people what to do or how to feel. I want it to be a loose guide, where readers are actively participating and putting themselves in these empty spaces. Space and silence are important to my own meditation practice, and, by extension, important to the art I create.

RLW: Your installation for “CTRL+ALT,” a pop-up exhibition sponsored by the Smithsonian Asian Pacific American Center, I’d describe as a transgalactic meditation on the life cycle of the earth. Similarly, in an Illustrated Guide to Becoming One with the Universe, your characters cross vast stretches of space. I’m struck by your sense of cosmic scale.

YS: I’ve always been interested in science fiction and magical realism. Sometimes using these devices makes feelings more real than a “realistic” setting. A lot of the meditation I do is thinking about the smallness of planet Earth in relation to the rest of the universe and how the nature of the universe can never be known. I think about that a lot—how the sun is eventually going to explode.

Space imagery just comes up for me naturally. The backdrop of space is a fascinating way to explore so many ideas I wouldn’t think about otherwise. The idea of becoming an Earth refugee makes me think about what’s happening right now with climate change. Or thinking about being able to telepathically send messages to a friend on the other side of the solar system makes me think of the relationships I have here.

RLW: Part of that installation, which involves a guided meditation, asks sitters to communicate with their ancestors about what happened on Earth—what one did or didn’t do to save the planet. I’m curious what comes to mind when you think of ancestors.

YS: I’m essentially the first generation of one lineage to break from the culture my ancestors came from. I attended a conference in Portland a year ago where the Vietnamese-American mayor from Orange County [Bao Nguyen of Garden Grove, California] said that not being able to speak the language of your parents is a form of violence. I’ve been thinking about how my cultural experiences, how I relate to the world, are very different from what my ancestors grew up with.

One way of dealing with it is challenging myself to read and speak Japanese better. Even though I can speak with my parents and I know enough to get around in Japan, I still feel a lot of shame that I don’t speak fluently. Not just language—I don’t have cultural fluency. There are so many nuances of life I’m illiterate in.

Also, I’m thinking about the future and space travel and technologies. With all the radiation in Japan, I’m wondering if in the future, the only way to visit my ancestors’ graves is through radiation-resistant drone technology or something. It makes me feel sad and helpless.

I’m probably not going to have kids, so there’s the ancestry that can or can’t come after me, through other lineages—the burden of bringing life into this world when the future is so uncertain.

A spread from Yumi Sakugawa’s The Little Book of Life Hacks (2017), published by St. Martin’s Press.

RLW: In both Ikebana and the “Moon Between the Mountains,” the main characters don’t communicate verbally. I’m interested in your use of silence. In America, silence is seen as weakness or disempowerment. Especially in an Asian-American context, there’s a lot of silencing and internalized silence. But I feel those characters complicate that idea. How did you find ways to give them agency?

YS: As a kid, I was painfully shy. And to this day, I’m more introverted than extroverted. If there’s a heated political discussion, I’m probably the one listening, not participating. I grew up with this fly-on-the-wall perspective on different social groups and situations.

As an artist I like the challenge of creating characters who don’t emote in traditional ways, how to show who they are as people without verbal expression. I think also it’s a very traditional masculine ideal that talking more is better. I want to subvert the narrative that silence is a form of weakness, a form of disempowerment. Sometimes silence, listening, is the most powerful thing you can do. We need more of that. Subconsciously, that’s why I’m drawn to those characters who aren’t speaking all the time. In real life, too, I’m interested in the person who’s quietly listening. I want to know what they’re thinking.

RLW: In Ikebana, the main character’s silence, as part of an artistic performance blending life and ikebana flower arrangement, acts as a mirror to the society around her, as she experiences it—from a crit session in school to street harassment to her mother’s abuse.

YS: I think Ikebana was my way of processing what my art education meant to me, and the ongoing question of what it means to be an artist. Two things had to happen. One, the protagonist had a very specific vision, and with or without an audience, or grades, or public approval, she was set on executing this performance. Two, whether or not she intended it to, [the performance] did affect one person’s life. It did create this new connection, a way of seeing, for another person, that was completely unexpected.

I definitely played around with a couple endings—in one, the protagonist opens her mouth, but I felt that wasn’t necessary. She was already speaking in her own language, and it reached this person in an intense and intimate way. I didn’t feel the need to add more to the story.

Editor's Note

Yumi Sakugawa’s The Little Book of Life Hacks is available May 2, 2017, from St. Martin’s Press.