Defining Difference: Hank Willis Thomas at the SCAD Museum of Art

In anticipation of Hank Willis Thomas’ new site-specific project for “Prospect.4: The Lotus in Spite of the Swamp,” Dana Kopel visits the artist’s two exhibitions at the SCAD Museum of Art in Savannah.

Installation view of Hank Willis Thomas’ Blind Memory (Cotton), 2017, at the SCAD Museum of Art, Savannah. Cotton. Courtesy the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

The violent history of anti-blackness in the United States weighs especially heavily in Savannah, Georgia. The site of the largest slave auction in the United States, which has been named the Weeping Time and took place not long before the Civil War and abolition, the city bears the traces of the countless enslaved black people who lived there and passed through. The SCAD Museum of Art presents two concurrent exhibitions of works by Hank Willis Thomas that engage, directly and indirectly, the history and aftermath of the transatlantic slave trade both locally and on a national, systemic level.

The museum is built around—essentially cradled within—the fragments of a 19th-century railway depot. Four shallow, glassed-in display spaces, known as the museum’s Jewel Boxes, have been built around arches in the original brick walls; Thomas’ “Blind Memory” is on view, from outside the building, in these. Each vitrine contains an installation of a single material that would have been exported from antebellum Savannah: stacks of pale cotton, a pile of tobacco, sheets of indigo-dyed cloth, a massive heap of rice. Created specifically for the exhibition, these four deeply resonant works explore how materials embody the history, and the grief, of a brutally racialized America—a line of inquiry Thomas will continue to pursue, in the specific context of New Orleans, in his forthcoming site-specific sculpture for “Prospect 4: The Lotus in Spite of the Swamp” this fall. The formalist installations in “Blind Memory” are at once sculptural works—the presence and accumulation of specific materials, in a particular (and particularly loaded) space, forms the core of each work—and images—flattened, textural monochromes behind glass panes. This imagistic quality links the works to Thomas’ broader practice, emphasizing his longstanding engagement with the production and circulation of images, particularly photographs and advertisements.

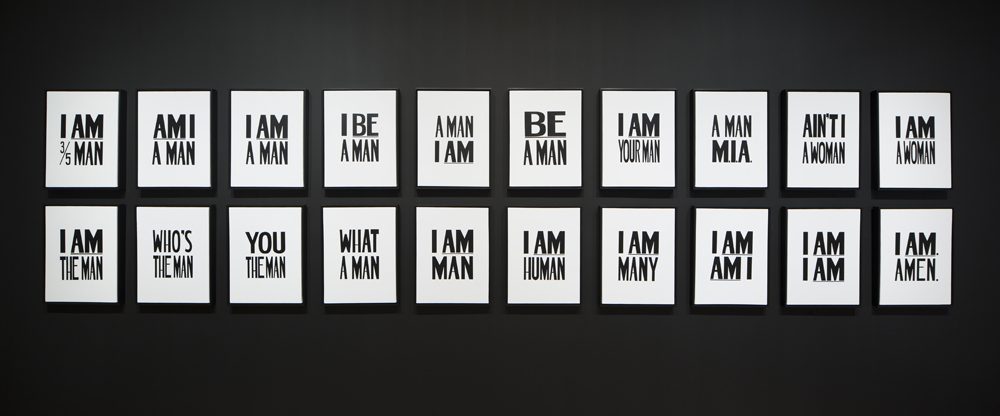

Installation view of Hank Willis Thomas’ I Am a Man, 2009, at the SCAD Museum of Art, Savannah. Liquitex on canvas. Collection of the Ulrich Museum of Art at Wichita State University. Courtesy the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

A number of strong examples of Thomas’ works from the past 15 years are on view in “Freedom Isn’t Always Beautiful,” in the museum’s Walter O. Evans Center for African American Studies. The exhibition opens with I Am a Man, 2009, perhaps the best-known of his works on view, a series of paintings that set the groundwork for the exhibition’s major thematic concerns: the relationship between language and image, the constitution and representation of publics, and the connections across intergenerational black experiences, especially within the United States. All rendered in black block letters on white backgrounds, the I Am a Man paintings are modeled after the signs carried by striking sanitation workers in Memphis in 1968 (though the phrase was used in struggles for abolition as early as the 18th century).

Black and white define the palette for much of the exhibition, a reference to race as well as to polarities of difference more broadly. For instance, in Zero Hour, 2012, from Thomas’ Wayfarer series, a collaboration with Sanford Biggers, a succession of photographic portraits shifts from white to black, revealing a sitter (portrayed by Biggers) painted sharply down the middle. Zero Hour generates the sense of a stark yet unfixed racialized divide, one that can be seen, at least metaphorically, within a single subject.

Hank Willis Thomas, Flying Geese, 2012. Mounted digital c-prints and stained African mahogany (detail). Courtesy the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

Other works more explicitly probe the history of anti-black racism, as in a constellation of reflective digital collages based on photographs by photojournalist Spider Martin, who documented many of the confrontations of the Civil Rights Movement. One of the works, Two Minute Warning, 2016, features the same photo—of the “Bloody Sunday” confrontation outside Selma, Alabama—as the controversial billboard erected in Pearl, Mississippi, by For Freedoms, the super PAC founded by Thomas and artist Eric Gottesman. Engaging the visual language of protest, Thomas’ works on view include reworked images of America’s Civil Rights struggles as well as giant protest buttons (All Power to the People and Wonder Woman, both 2015) and slogans, at once pointed and cryptic, rendered in neon, aluminum, or lenticular prints.

Occasionally his critiques risk coming across as simplistic, in the manner of Adbusters-style anti-advertising imagery—as in Branded Head, 2003, a photograph of a black man’s shaved head branded with the Nike logo—but more often the works’ criticality is matched by a conceptual rigor and formal elegance. With All Deliberate Speed, 2015, a screenprint on retroreflective vinyl, contains a trick: While the work appears faded, almost illegible, to the naked eye, taking a flash photograph of it reveals a white man stabbing at a black man with a large American flag, an image—now eerily glowing—originally taken at a Boston protest in the 1970s. The encoded imperative to take a photograph of the work implicates the viewer, makes her complicit in the violence of what’s depicted—you take the photo, take it with you in an act of capture and possession. Such an act gets at the crux of Thomas’ practice, which continues to draw out tensions between witness and participant, and—relatedly—between the slick surfaces through which we represent reality and the sometimes violent complexities that bleed through.

Editor's Note

Hank Willis Thomas’ “Blind Memory” and “Freedom Isn’t Always Beautiful” are on view through August 20, 2017, at the SCAD Museum of Art (601 Turner Boulevard) in Savannah.