The Black Market: Kevin Brisco Jr. at Good Children Gallery

Imani Jacqueline Brown looks at Kevin Brisco Jr.’s newest body of work, which questions how society places value on art objects and human lives.

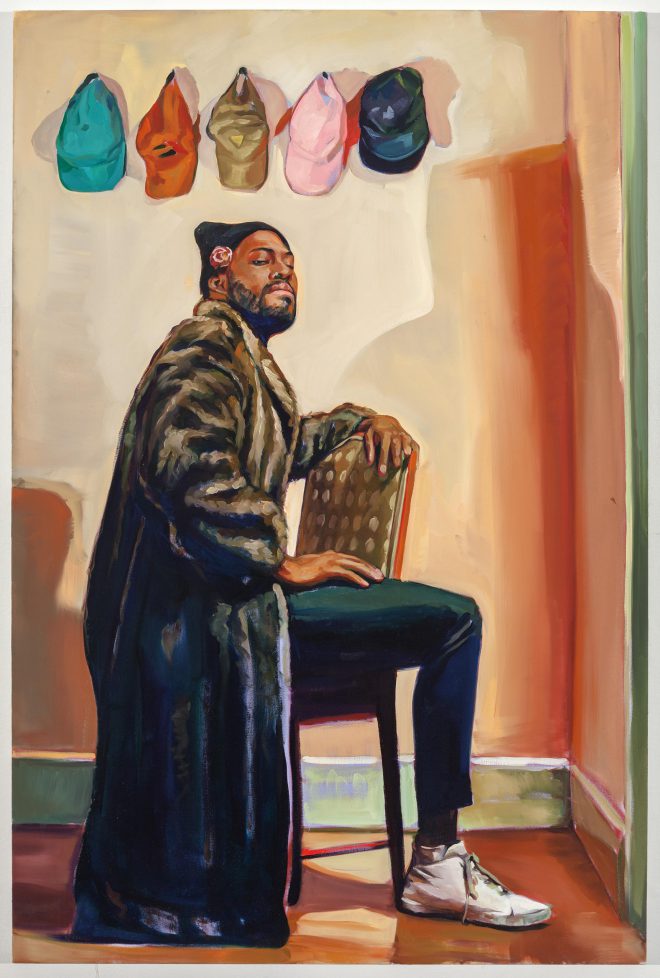

Kevin Brisco Jr., Randall, 2017. Oil on canvas. Courtesy the artist.

The first thing you see in the gallery is life: Three palm trees mark the center of the room. In our world of air pollution and air conditioning, there is much to be said about the ability of plants to filter and revitalize stagnant, indoor air. Perhaps the flora is a welcome addition that helps to enliven an insular contemporary art scene that is all too ambivalent about the outside world. But the plants aren’t the only signs of life here. The walls are hung with twelve vibrant canvases radiating with floral patterns and fur, late afternoon light and brown skin, drawing the viewer into warm domestic spaces with graceful, gliding brush strokes, compelling you toward their subjects: three black women and three black men alongside three opulent floral arrangements from New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Hope Diamond, a chandelier from the Palace of Versailles, and a trashcan lid.

The people in Kevin Brisco Jr.’s paintings—all from 2017—in “(For) What Is(s) Worth” at Good Children Gallery include friends (Randall and Nondi), neighbors (Ronald and Terrence), a fellow artist (Ashley T.), and the artist’s partner (Ashley M.). Though they hang in an art gallery, these people are not for sale. They defy their objecthood and insist on being more than commodities for speculation on the art market. Brisco has stipulated that these paintings may not be purchased by private collectors. The portraits may, however, be acquired by museums or institutions that intend to publicly display the works, allowing Brisco’s subjects to be included alongside the white bodies that dominate the Western artistic canon. Some collectors have seen the show, and they are not happy, according to Brisco. Emboldened by their wealth, they are used to getting what they want and are unnerved by the ease with which Brisco has denied them the objects of their desire. They recognize that he has somehow devalued the source of their power.

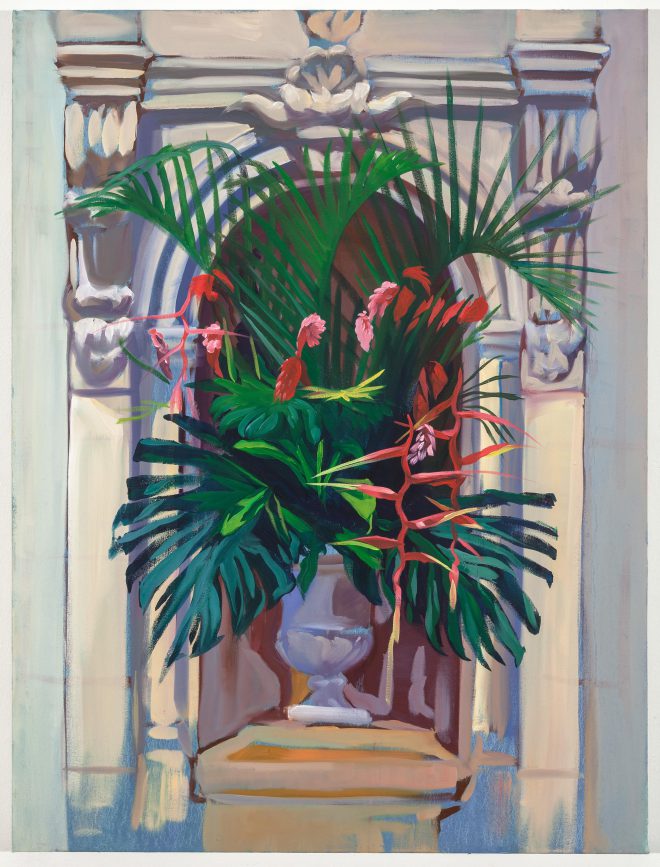

Brisco’s paintings of objects are salable, however. They are priced between $800 and $3200, depending on the size of the canvas and the amount of labor put into each piece. The juxtaposition of the Hope Diamond alongside a trashcan lid alongside portraits of human beings carries Marcel Duchamp’s readymade project to its logical, capitalist end: Brisco lays out the artificiality and absurdity of a value system wherein objects can be worth more in real life than on canvas while portraits can be worth more than their subjects.

Kevin Brisco Jr., Great Hall Floral Arrangement at the Metropolitan Museum of Art (Heliconia, Ginger, and Areca Palms), 2017. Oil on canvas. Courtesy the artist.

In a capitalist society, humans and objects are unmoored from their normal places along the hierarchy of value. Some people become objects—a means to an end—while others become objectifiers, receiving social worth from their possession of objects. In antebellum New Orleans, black people, land, art, and other “property” were auctioned in lavish, spectacular performances of valuation and objectification. Drained to three-fifths of their human value, black bodies became stores for and signifiers of their owners’ wealth, similar to the function of gold, currency, or stocks. At the end of the transatlantic slave trade in 1807, the value of black bodies skyrocketed as demand surpassed supply; after abolition, the value of black bodies plummeted. Black bodies are the canaries in the coalmine of a global crisis of values.

According to corporate CEO and art collector Larry Fink, contemporary art has surpassed gold as one of today’s greatest stores of wealth. Earlier this year, Jean-Michel Basquiat’s untitled painting of a skull from 1982 was sold for $110 million, nearly 30 years after the artist’s death and three years after Michael Brown’s body was left lying in the street for four hours in Ferguson, Missouri. At a 2014 talk at the Contemporary Arts Center produced in conjunction with the institution’s presentation of “30 Americans”—an exhibition of works by 30 black artists from the collection of white collectors Donald and Mera Rubell—Mera Rubell reminisced about choosing to leave New Orleans as a young adult because she found life under Jim Crow to be too much to bear; today, she and her husband collect black artists because she finds their work “challenging,” to use a word from her talk.

“(For) What Is(s) Worth” is an answer to Brisco’s last presentation at Good Children Gallery in July 2016, when he chose to host a performance about the recent killings of black people by police rather than display permanent art objects. Alton Sterling had been murdered in Baton Rouge the week prior to the opening, yet still gallery visitors complained to Brisco that they “were hoping to see some paintings.” Dismayed, he asked himself how else could he use art to drive home the point that “black bodies are undervalued in this society.” Brisco’s refusal to sell his community into the spectacle of art-market speculation—even working against his own self-interest as an emerging artist—is a radical act. This type of work is necessary to undo the damage that capitalism has wreaked on our humanity.

Brisco has the hand of a magician; the spells he has cast over this space shoot from the eyes of his people and crackle with heat. They look right on past you, denying your power as viewer, spectator, consumer, buyer—Ashley T. is staring off into the distance; Terrence is immersed in his phone—or they meet the challenge of your gaze—Nondi’s reading you, but she reveals nothing but a churning and impenetrable depth of expression; Ronald is throwing shade. Brisco has captured silent laughter dancing behind their eyes. They let you stand there and look, but you can’t touch. They don’t need you. You can’t own them.

Editor's Note

Kevin Brisco Jr.’s “(For) What Is(s) Worth” is on view through August 6, 2017, at Good Children Gallery (4037 St. Claude Avenue) in New Orleans.