On Full Existence: William Eggleston at the Ogden Museum of Southern Art

Laurence Ross contemplates William Eggleston’s focus on the everyday and the effect that has had on contemporary photography.

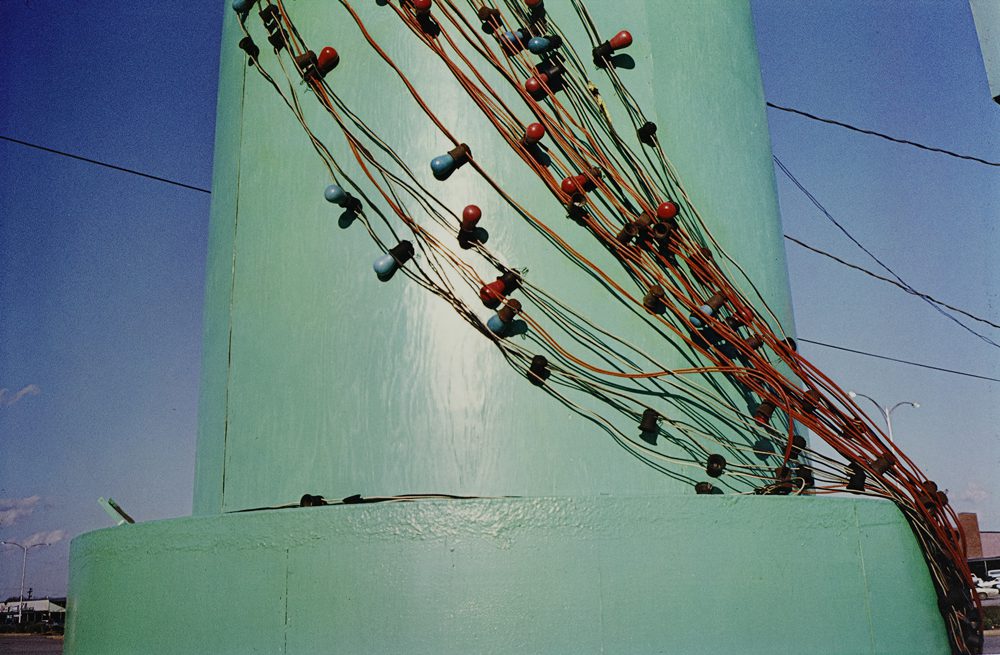

William Eggleston, Untitled (Plate 11 of 15 from the Troubled Waters portfolio), 1980. Dye-transfer print. Collection of William Greiner.

…it would be our business to show how through every instant of every day of every year of his existence alive he is from all sides streamed inward upon, bombarded, pierced, destroyed by that enormous sleeting of all objects forms and ghosts how great how small no matter…

James Agee, Let Us Now Praise Famous Men

In part, what makes William Eggleston a remarkable photographer is his choice of the unremarkable as his subject. The subjects of his Troubled Waters portfolio, 1980—now on view at the Ogden Museum of Southern Art—can be parsed into two worlds of consideration: the human narrative and the forms that persist without us. Images like those depicted in these 15 photographs are often witnessed unconsciously: muddy water pooled in a tire track, a pinball machine, piles of cardboard and garbage. In daily life, focusing our attention on the quotidian seems like a waste. These images do not often register, much less cause conscious consideration—but it is through these images that we, as viewers, can see the imprints of our lives.

However, the surfaces of Eggleston’s prints are just as important. Seen simply as shapes and fields of color, these images are often beautiful, even joyous. In one photograph, strands of blue and red bulbs wrap around a pole and ally with the shape of the power lines draped in the blue sky beyond. Delight can be found in the column’s gradations of green, and we can see Eggleston play with lines and edges, textures and tilts, juxtapositions of color. He manages to nudge the perspective slightly upward into a striking composition.

William Eggleston, Untitled (Plate 15 of 15 from the Troubled Waters portfolio), 1980. Dye-transfer print. Collection of William Greiner.

Color photography, which was widely available to the public before 1980 in the form of the point-and-shoot camera, had been long considered by the art world to be somewhat pedestrian. There were exceptions, of course, but color was the medium in which people catalogued their mundane lives. To many, it seemed nothing artistic could arise from the color film that became quintessential of the American family, employed to chronicle vacations, holiday cookouts, birthday parties, and high-school graduations. If photography had a place in the art world, that place seemed to be strictly black and white—the pioneering visions of Walker Evans, Ansel Adams, Alfred Stieglitz, and Diane Arbus.

Eggleston, who is often considered the father of color photography, is credited with breaking through the barriers surrounding this relatively new tradition. (His 1976 exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York was one of the first museum exhibitions dedicated to color photography.) The Tennessee-born photographer was influenced early on by the work of Evans, Robert Frank, and Henri Cartier-Bresson before stumbling upon dye-transfer printing, a process of color photography that was primarily being used for commercial advertisements. Of course, there were photographers prior to Eggleston who had experimented with color, but Eggleston elevated the practice to technique. With a new mastery of both composition and color, he made images that still arrest our attention and that have influenced contemporary ideas of what fine art is and can be.

When I think of William Eggleston, I think first of his portraits. I think of the Mississippi grocery boy in an apron pushing a short row of shopping carts in the warm hues of the sun. I think of a young man slumped in a large chair amidst a pool of green curtains, offset by a red lamp shade. I think of an old woman smoking a cigarette outdoors, seated on a cushioned sofa with its springs exposed, and the clash of floral patterns—dress and upholstery violently vibrant. Though regardless of whether Eggleston was aiming his camera at a person, place, or thing, the photographs still manage to convey portraiture. When there is a face, the portrait is a bit more straight forward; when we are presented with the objects that make up a place, the portrait is a ghost of whom we do not see. In both cases, Eggleston’s photography communicates presence.

William Eggleston, Untitled (Plate 6 of 15 from the Troubled Waters portfolio), 1980. Dye-transfer print. Collection of William Greiner.

Take, for example, one photograph from Troubled Waters: the inside of a freezer, haphazardly packed. This is a portrait of preparedness and neglect—a burial of food upon food still waiting to be defrosted. We see, through this frame, a window into the common human conditions of accumulation and abandonment. Tension exists between clutter and sparseness. We may consider what we accumulate and, alternately, what we abandon. We see how we live because Eggleston has documented it.

We live through an enormous sleeting of objects: vanilla ice cream, beef pies, corn, condensed grapefruit juice, perhaps chicken, perhaps pork chops. Two ice-cube trays sit isolated, mostly empty, and left slightly aslant, holding nothing of use. And then there are the colors: baby blue, powder blue, cerulean; yellow, tan, camel; black and red letters angled every which way. This is a maelstrom of once-consumable objects, packaged and labeled, that seem no longer destined to be eaten. Somewhere, the anticipated narrative has gone astray. The future (of a meal, of a family, of a life) gone awry; an expectation shaken, disturbed. Through a scrim of frostbite, one senses disruption.

Eggleston did for color photography what Duchamp once did for the found object, or what Eggleston’s contemporary Andy Warhol did for pop culture—lending the context of the museum to what had previously been considered supremely banal. In each of these cases, the artist ventured to challenge the conventions of the time and elevated the familiar to the extraordinary. Is there a more artistic gesture than to make the ordinary new again? Perhaps this is always the artist’s experiment: how to deal with the modern world in all its ragged difficulty, its troubled beauty.

It may be easy to view Eggleston today and forget the leaps he made because we are now inundated with a never-ending livestream of colorful images that we can make more vibrant, more saturated with the swipe of a finger. One of the great pleasures of Instagram is to see objects arranged on surfaces with the light just so, the color brilliant. Though few of these images will have the staying power of Eggleston’s work, as now this type of arrangement is less novel, codified as a recognized genre. Instagram may thrill at the beauty of an arranged surface, but what of the depth? Do we register these iPhone photos as an imprint of our lives? I wonder what Eggleston would think of Millennial Pink.

William Eggleston, Untitled (Plate 9 of 15 from the Troubled Waters portfolio), 1980. Dye-transfer print. Collection of William Greiner.

Eggleston studied pink nearly 40 years prior: a rural gas station, cast part in twilight, part in neon. The tension between man and nature would be too simple a read here: the dark burst of a tree behind a graceless, geometric structure; pump stations standing at the ready to fill our cars with precious earth to burn. How is it that we suddenly see beauty in a gas station? Though closed for business, this vacant lot lays open a metaphor, pressing: What is our use; what are we lacking; what destination are we trying to reach?

Many of the photographs in Troubled Waters depict empty spaces—environments of the after-hours, when life has quieted or halted. In one print, a jukebox casts its glow on the clean, reflective surfaces of the diner tables. Salt, pepper, sugar, ashtray, all set for the next shift. Here, we inhabit an eerie in-between. We might become an interloper, a trespasser, or an unwanted guest. Even Eggleston has managed to erase himself from this shot, somehow positioning the camera in a way that we do not see the photographer’s image in the fisheye mirror overhead. Eggleston leaves us in these habitats, unattended. And it is often lonely, to sit with ourselves.

Perhaps the true horror of Troubled Waters is this: Through the medium of photography, Eggleston demonstrates that people will not forget what they have seen. He has captured more fully than we thought possible the way we are, the way we live. Not the narratives we tell ourselves or the edited versions we offer up for others, but the real proof of our lives. The empty gas station at twilight, the freezer jammed and not defrosted, the carnival lights wrapped around the green trunk of an electrical tower—undeniably our stuff, and undeniably human. Perhaps, through Eggleston, we see our worlds more fully than we ever imagined, ever wished. Our worlds are not rendered in black and white, a filter that can easily elevate, lend itself to a flattery as our flaws are concealed amidst the high contrast, the shadow. Here, our worlds are shaped in all their color, a saturated view of what it means to be human, worlds in which we may feel together yet alone.

If there is trouble here, it is that we horrify ourselves. These are photographs of unedited existence. These landscapes indicate a before and after, their absent folks. When we look at our own image, we want to see ourselves cast in a flattering light. Though we all have many faces (and many masks), our “best” face is the one we hope we present to the world. What is truly disturbing about Eggleston’s photography is that he shows aspects of ourselves that we typically display only when we think we are alone. Or when we think no one is paying attention. Or when we think no one is looking.

Editor's Note

William Eggleston’s Troubled Waters portfolio is on view through October 26, 2017, at the Ogden Museum of Southern Art (925 Camp Street) in New Orleans.