Timely Tribute: The Rise and Fall of Opera’s Voices

As part of our series on female celebrity, Ben Miller wonders what an opera singer must give up in order to achieve divadom.

Italian opera singer Anna Moffo in 1962. Image via Classicalite.

An anecdote from Wayne Koestenbaum at soprano Anna Moffo’s wake: “I signed the ‘Relatives and Friends’ book, but didn’t write down my address. I feared that her stepchild or cousin would send me a chiding letter: ‘You had no business attending Anna Moffo’s wake. Wakes are for intimates.’” The husky-voiced Moffo, subject of poetic odes and namesake of the great term “Moffo Throat,” was surely not the first nor last singer to inspire feelings of intimacy in strange queers. Nor am I the first queer to point out such a phenomenon. Koestenbaum’s classic The Queen’s Throat: Opera, Homosexuality, and the Mystery of Desire theorizes opera as a paradigm of homosexuality whose “hypnotic hold” is rooted in the gendered “interlocking of words and music.” Key, too, is the eroticization of vocal production: so much uncloseted emotion produced from such fellatic throatiness.

As opera fades from popular interest and great opera divas die, we opera queens who live increasingly feel we are attending the wake of opera itself. Considering the public scrutiny of today’s pop stars, it seems productive to examine the relationship between female opera singers and their audiences and between those singers’ voices and bodies—to contrast our love affairs with singers’ voices and the difficulty of imagining those singers as human people. Why, and how, do we consider ourselves their intimates? What price do they pay for our intimacy?

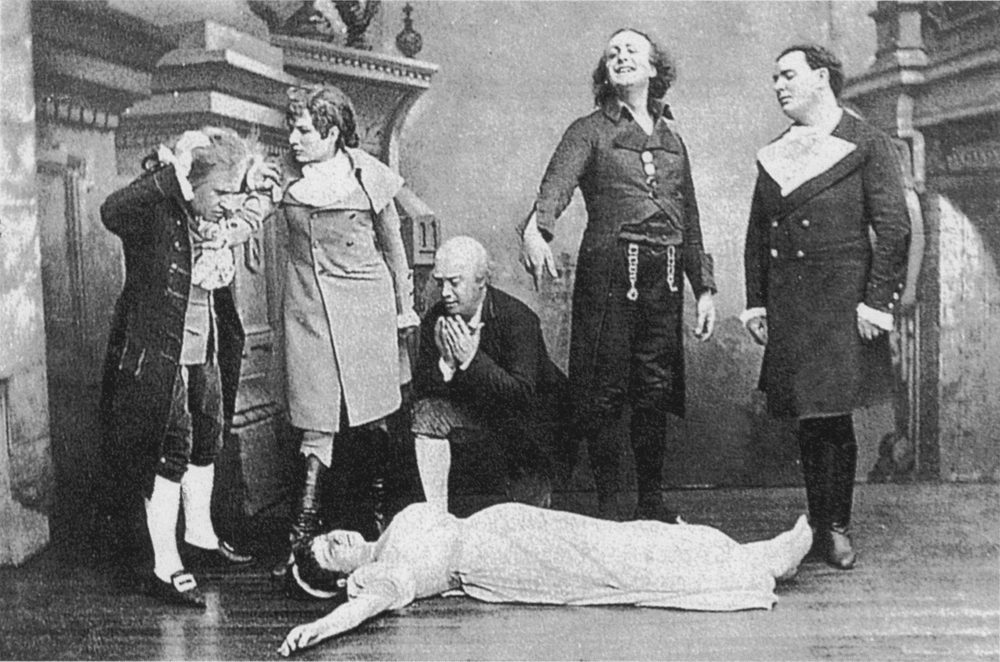

Felicia Miller Frank offers a starting point in The Mechanical Song: Women, Voice, and the Artificial in Nineteenth-Century French Narrative. She reads E. T. A. Hoffmann’s tales of Antonia and Olympia as evidence of the voice’s attachment to feminine fragility and subjugation. In the former, a woman’s astonishing singing voice comes from a physical defect from which she eventually dies; in the latter, a doll sings so enchantingly as to cause the narrator to fall in love with her. Interestingly—though Miller Frank neglects to mention this—these tales were themselves turned into a 19th-century French opera. The doll’s song (from Jacques Offenbach’s Les Contes d’Hoffmann) is one of those scarcely believable flights of coloratura that might inspire an audience to believe the singer possessed, artificial, defected.

In an examination of George Sand’s Consuelo—an epic novel telling the story of a Spanish opera singer who travels, often disguised as a boy, from Venice to Vienna to Berlin to Bavaria—Miller Frank explores the connection between voice, soul, and body. In the beginning of Sand’s novel, a character is “shocked” to find that Consuelo’s beautiful voice comes from her ungainly body. “By insisting on the discrepancy between Consuelo’s plainness and the loveliness of her voice,” Miller Frank argues, “Sand works in a different direction, seeking to…relocate [the feminine voice’s] resonance on a moral and artistic plane.” The voice has an independent power; it is its own subject.

The death of Antonia, as performed in the first production of Jacques Offenbach’s Les Contes d’Hoffmann, 1881, at the Opéra-Comique in Paris. Image via Wikimedia.

And that moral relationship to female singers continues. Two anecdotes: I remember sitting in the audience at a Dawn Upshaw recital a few years ago when an older woman leaned in next to me, conspiratorially: “You’d never know, but when she’s offstage, she’s a real frump. She looks like the cleaning lady.” And on the popular opera-gossip website parterre box, the visit of the legendary mezzo-soprano Fiorenza Cossotto to the New Orleans Opera in the 1970s is remembered with horror by a user whose nom de plume is “Enzo Bordello”: “Up close and in person, Cossotto was a thoroughly unpleasant little fireplug of a woman, obsessed with her own need for attention…one look at La Cossotto and I knew any prospective mugger would regret accosting this diva…She wore huge spike heels to compensate for her short stature…flabby arms.”

The fallback for singers, of course, is the voice: The woman next to me swooned as Upshaw crooned Claude Debussy’s Poèmes de Baudelaire, and even Bordello eagerly writes that “[o]n stage, Cossotto was a figure of mystery and fascination, an impression enhanced by that immense powerhouse of a voice...My eardrums vibrated for hours afterwards. It's hard for the junior queens to understand what the impact of such a voice is like. But once experienced, you never forget it….”

The separation of the body from the voice—godly, artificial, perfect, spoken of in the third person as though it has volition independent of the woman’s body and mind—is central here. We can’t help but expect that women with such gifts should be as physically and temperamentally gorgeous, captivating, and perfect. How could they not disappoint?

But voices change and fade. Take the case of dramatic soprano Deborah Voigt, who, following gastric bypass surgery, found herself in increasingly dangerous vocal territory. In a fan-made YouTube video, an unflattering photograph of the pre-surgery Voigt is shown, accompanied by a recording of a celebrated Carnegie Hall performance of the battle cries from Brünnhilde’s entrance in Richard Wagner’s Die Walküre. Next, we see a stapler and hear its crunching sounds. Finally, a glamorous studio photograph of the thinner Voigt appears with a new recording of the same song in which her voice has unmistakably hardened. The top comment: “What a catastrophic difference…She sacrificed voice to look like Lindsay Lohan.” More: “what I'd like to see her do is the Dance of the Seven Whales.” Misogyny, fatphobia, and fan indignance all contribute to the seeming glee with which her decline is celebrated, a glee that stems from the rush of seeing Voigt’s human flaws.

Part of the thrill of operatic voices for queers, I think, is their sense of limitlessness, their ability to contain immense emotion and to seem so powerful that they can exist forever. Alexander Chee, interviewed about his 2015 novel The Queen of the Night (a lovely go at Consuelo-like material with sparkling, postmodern twists), spoke of this quality: “I have joked that it is yet another autobiographical novel from Alexander Chee. But I think the autobiography in this—to the extent that there is any in this—is in things like: When you are a professionally-trained singer in a boys choir, you are very aware that there is a time limit on your voice. And I think it was then that I began to become fascinated with women sopranos who seemed to have less of a limit because I loved my voice so much as a child and I couldn't imagine myself, once I could sing with it, I couldn't imagine who I would be without it.”

Who is a soprano without her voice? The voice can be reworked into a mezzo in certain cases. Or the voice can retreat to memory. In Fred Morin’s CALLAS RELOADED, 2014, a Maria Callas concert is re-edited to include only the applause. The aggressively faded singer has leveled up into a pure, voiceless figure of grace and poise. She retains her artificiality, her ghostly resonance; here, it originates merely from her presence. The cheers resound, now louder, now softer. Callas blushes, beckons, twitches; she adjusts her wrap and finds her light.

And, in our imaginations, these divas can even regain their voices. Wayne Koestenbaum dreams of Anna Moffo’s late-career Carmen, an imagined performance long after her voice was gone: “I (once more) proclaimed her greatness, though no one listened. Her clear, restrained instrument: Anna in 1979 was unbesmirched, her pitch intact again, early. I wish I’d offered timely tribute.”