Reformation: Public Art and the Philadelphia School Closures

Meredith Sellers looks at artist Pepón Osorio’s newest installation in Philadelphia.

Installation view of Pepón Osorio’s reForm, 2015, at Temple University’s Tyler School of Art, Philadelphia. Photo by Constance Mensh.

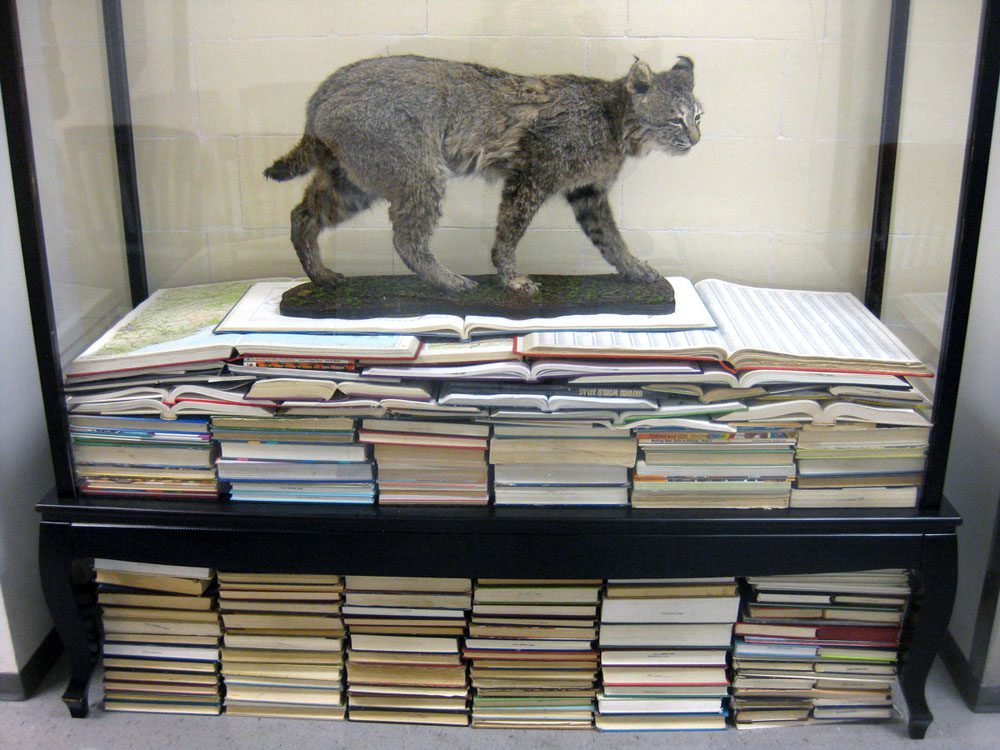

After about ten minutes of wandering around Temple University’s Tyler School of Art, I saw students emerging from a hallway. No one had been able to tell me the room number or exact location of the classroom where reForm, artist Pepón Osorio’s newest installation project for Temple Contemporary, was located. I slipped past a pair of double doors and had started walking down the hall when I realized I was already inside the work. Brightly colored backpacks hang from a row of wooden cubbies with sneakers, jackets, and stuffed animals stashed inside them. Photos of empty hallways, scattered file folders, and a recent student reunion party are embedded within clunky frames into a false cinderblock wall behind the cubbies. A sullen looking taxidermied bobcat is perched on a massive pile of books inside an antique vitrine.

I turned the corner and entered a classroom. The main exhibition takes place in one of Tyler’s art history rooms, which, the wall text informed me, will continue to be used through the duration of the exhibition. Over a chorus of children’s recorded voices the gallery attendant asked me to sign in the guestbook. The children are speaking about their now-closed school, Fairhill Elementary, from video screens attached onto oversized pencils decorated with chock-a-block assemblages of mirrors, tchotchkes, and loudspeakers. The assemblages are peppered with plastic figurines holding miniature protest signs saying “The Kids,” “SOS,” and “Fight Hite!” The ten young people on the video screens, mostly graduates of Fairhill, form what the project calls the Bobcats Collective, after their former school’s mascot. The students chant lines from a poem one of them wrote, “This time when we speak, you listen,” and, “Jail or dead, dead or jail.”

The students’ concerns are real, yet the classroom installation is filled with cloying surrealistic interventions, like a fake tree sprouting out of a sink and backpacks suspended from the wildly patterned ceiling. There are random assortments of artifacts salvaged from the school—piles of books stacked haphazardly against a wall, teacher’s mailboxes, and a nurse’s vinyl couch that stands in front of a wall with a chalk rendering of Superintendent William Hite’s letter informing parents of Fairhill’s closure. The walls of the room are lined with blown-up prints of essays the students wrote about their feelings on the school’s closure, marked with paternalistic red ink corrections. After a couple minutes the children’s protestations loop and repeat, and by the time I’m leaving the installation, they’ve started to grate.

Across town in South Philadelphia, there is a line a block and half long to get in the door at Edward W. Bok Technical High School. The school, a towering Art Deco gem, has been shuttered since the 2013 school budget crisis, along with 23 other public schools in the district, including Fairhill. It was bought recently for $1.75 million by Scout Ltd, a real estate company lead by Lindsey Scannapieco, the daughter of one of Philadelphia’s real estate tycoons. The line is not comprised of students, but rather young urbanites, waiting to get into a pop-up bar at what’s being marketed as “Philadelphia’s greatest new rooftop.”

The bar is called Le Bok Fin, in reference to the technical school’s culinary program, which in turn was a nod to Le Bec-Fin, one of the city’s former premier restaurants. The rooftop is outfitted with furnishings similarly salvaged from the school—chemistry lab tables with tall-backed chairs and plastic stacking chairs in an array of colors. The pop-up beer garden is temporary, an introduction into a space that Scout says, once everything is brought up to code, will be “a new creative eco-system that seeks to reuse and repurpose existing infrastructure for makers, innovators, and entrepreneurs in South Philadelphia,” as well as a new dog park, a bike repair station, and a redesigned bus shelter made possible by an almost $150,000 Knight Cities Challenge grant. Whereas 93% of Bok students were young people of color and 97% would be categorized as low income, to scroll through Instagram photos tagged with #lebokfin is to wade through a veritable sea of sunset pics, Wayfarers, and whiteness.

Bok, as a technical school, was a much-needed space to train students with hard skills and certifications to help them out of poverty and into jobs. Unsurprisingly, the school’s recent appropriation has caused a local Internet uproar. The image of privileged people clinking glasses atop the husk of a public school, while the district struggles to meet even the most basic needs, does not sit well. It has ignited a conversation about what the fate of these buildings should be once they’ve been stripped of their designated use, and also what our collective responsibility is toward protecting a basic civic right—affordable, quality education—from privatization and lack of accountability. According to a 2011 report from the Pew Charitable Trust, “selling or leasing surplus school buildings, many of which are located in declining neighborhoods, tends to be extremely difficult. No district has reaped anything like a windfall from such transactions. As of the summer of 2011, at least 200 school properties stood vacant in the six cities studied—including 92 in Detroit alone—with most having been empty for several years.”

This is the state of the school system in Philadelphia after Pennsylvania House Republicans and former Governor Tom Corbett cut $1.1 billion from the state education budget in 2012, leaving the city school district with a $304 million deficit. Corbett’s intent was to strangle what he considered to be a failing education system in favor of privatized for-profit charter schools, which take public money from the district, in addition to raising their own separate funds from corporations and other sources. The Philadelphia school district, lead by Superintendent Hite, did the only thing it could—made cuts. Philly schools were, and largely still are, bereft of counselors, hallway monitors, cafeteria workers, secretaries, afterschool programming, sports, art and music, textbooks, and in some cases even desks and chairs. One sixth-grade student died of an asthma attack because her school nurse, like nearly all nurses in the district, had her hours reduced to just two days per week. Nearly 3000 teachers lost their jobs and class sizes ballooned. As schools closed, their students were sent to neighboring schools, further increasing the strain.

In June of this year, a budget proposal by new Democratic Governor Tom Wolf aimed to restore nearly all the lost funds to the school system. The budget has been mired deep in partisan politics at the state capitol in Harrisburg, blocked by Republican lawmakers, and remains unapproved.

Back in North Philadelphia at 6th and Somerset Streets, Fairhill Elementary sits vacant, and in this neighborhood, where 57% of residents live below the poverty line and median household income is $14,185 a year, it is likely to do so for some time. This past December and again in May, Pepón Osorio organized a reunion of sorts on the school’s grounds with the Bobcats Collective to “help the community heal from trauma,” as Tim Gibbon, the Project Manager for reForm and a former teacher at Fairhill, told me. Gibbon expressed a feeling that the school had been targeted for closure long before the announcement, slowly drained of resources as students were siphoned off by wealthier charter schools, then accused of being below capacity with low test scores. He tells me that the Bobcats will be participating in a few workshops throughout the duration of the show, though the nature of the workshops is undetermined.

Installation view of Pepón Osorio’s reForm, 2015, at Temple University’s Tyler School of Art, Philadelphia. Photo by Meredith Sellers.

The reForm project, funded by The Pew Center for Arts and Heritage and the Surdna Foundation, aims to create much-needed public discussion around the fate of the Philadelphia school system and to be a potential catalyst for change. But a classroom, tucked down a labyrinthian hall, inside a building on a university campus hardly feels public. Beyond this tenuous relationship to publicness, reForm stumbles to empower those it seeks to help—a hallmark of successful social engagement artworks—and seems hemmed in by the artist and his aesthetic preferences. The fact that the students involved in the project were hand-picked, and most had already graduated by the time of the school’s closure, speaks to an interest in the aesthetics of the project taking precedence over the social necessity. If the project is about students’ trauma, why not engage with the students who were at the school at the time it was closed, regardless of their age? If the project is about healing, why not work openly with directly affected students in a project that’s appropriate for their grade level?

Like Le Bok Fin, reForm does, however, serve as a reminder that there are no immediate answers for the important socio-political question of how a school district can right itself after decades of neglect and divestment, especially with such deep philosophical differences between the needs of the mostly Democratic city and the desires of largely Republican state politicians. It is not an easy task, but a truly generous public arts engagement must conceptually fulfill the needs of its constituents without aestheticizing their pain. In a twist of irony, it seems the project that has truly engaged the larger public in a conversation about public education in Philadelphia is not the one that attempts to restore students’ voices, but rather the vulture that seeks to profit off of the corpse of their former classrooms.