My Hair Without Me

Ann Hackett candidly and poetically discusses her experience with hair loss.

Sarah Pucill (After Claude Cahun), Quilt, 2013. Photographic print from negative. Courtesy the artist and the Jersey Heritage Collections.

Without me my hair holds water. One pound, two pounds, three pounds, ten pounds. Woven tightly and stretched taut across the shower drain. Rolling into tumbleweeds against the swishing motion of a broom. Breaking off into kindling in my hands. It may be lounging atop your dinner or floating lazily in your cocktail.

I tell a new friend that I may be losing my hair. She replies, “You are. I mean, I did. For a period of about six months it was very bad.” I look at her. Straight, strawberry blonde hair, falling almost to the small of her back. My hair has never grown that far past my shoulders without breaking. She offers solutions—an experimental treatment that can be purchased on amazon dot com. More importantly, stress management solutions: meditation and exercise. Stress is the perpetrator.

“But could it be my diet?” <br/k> “Unlikely,” she says. “Stress. Stress causes women to lose their hair. Are you very stressed right now?” We stand on the balcony of a vacation home in Southampton overlooking a pool. It is mid July. She wears a polka dot bikini. I sip a can of beer. <br/k> “Maybe.” I say. Recent studies show that even moderate stress can be lethal.<br/k> “Root out the stress-causing aspects of your life,” she says. I must learn to cope.

I have a roommate in Southampton who finds strands of my hair around the house. He photographs them and sends me the pictures via text message. I think it is intended to be endearing. He is, I believe, attracted to me.

After some delay, I decide to see a doctor, a dermatologist. The doctor begins by assuming I am overreacting. All women experience hair loss. She begins tugging at my hair. The most likely cause of hair loss is stress. There is really nothing she could do about that. I will have to work it out inside that head of mine. Nothing. But she will do some blood tests. She will test for a thyroid condition. And Rogaine. All women over twenty should use Rogaine. Even she used to use Rogaine until she realized there were more important things in life than her hair. Her marriage. Her child. Even as a dermatologist she sees hair for what it is, a vanity, plain and simple, and a waste of her time. She leans forward, places her hands on my temples, and traces out two circles on either side. “Touching the temples helps sooth the mind,” she says. “I can tell this will be a good year for you,” while rubbing my temples, “you have good things coming,” she says, as if I am crying—am I crying? My eyes may be watering from the air conditioner.

I know that there are more important things. I am keenly aware. Hair grows everywhere on the body except for mucus membranes and glabrous skin (eyes, nose, palms, footpads, lips). Medium brown and of medium thickness and medium waves. In high school, I warred against my hair with straightening, relaxing products, and constant darkening. By now, in my early twenties, I am resigned to its middling nature, its refusal to grow well past the shoulder, and I am tired of struggling with it. It seems that my least-loved feature might pass quietly away strand by strand. In 1984 a New York Secretary has her head forcefully shaved by a coworker’s wife and wins a lawsuit worth 117,500 dollars. I buy the Rogaine.

I see an acupuncturist. She tells me that my digestive tract is wrong, knotted, causing me to lose my hair, to tire easily, to experience depression. She can tell that I am depressed. She directs me to a table, unbuttons my shirt, and sticks needles in my feet and stomach. She hammers my skull with a surface made up of needles as the air conditioning chills my bare skin and her matted black curls bounce against her back. She gives me a hammer to take home and tells me to hammer my scalp every morning. Follow by dousing my head in vinegar.

A third doctor tells me he will most likely prescribe a hypertension pill that blocks testosterone production in balding males. Overproduction of testosterone causes balding in men. It is evidence of virility. “Not for you, I guess,” he says, and absentmindedly runs a hand through his reddish brown hair. If a man have long hair, it is a shame unto him? But if a woman have long hair, it is a glory to her (Corinthians 11:14-15). Glory unto him, glory unto him, shame unto him. He hands me a sheet of paper where he has written ROGAINE. “Come back in three months, then we’ll really know something.” I don’t tell him that it’s been over nine.

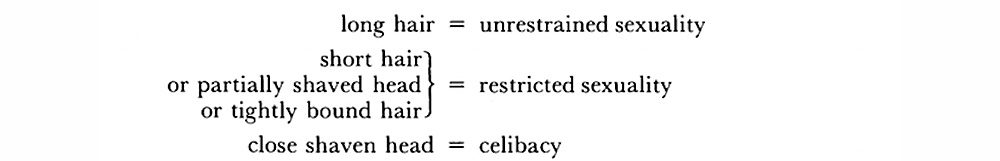

I have lunch with a female friend. “Your problem is sex,” she says, taking a bite of sandwich. “Stop having sex on your back. The motion ruins your hair.” She tugs emphatically at the back of her head grasping a chunk of smooth brown hair, bone straight. I propose the idea to my partner. He agrees. We don’t have sex. Instead he kisses me on the forehead. In 1958 E.R. Leach publishes an article in The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland. Leach found that in several Hindu religious practices in southern India, the head hair of a woman is a substitute for her genitals i.e. a ceremony involves parting the hair of a pregnant woman (Leach 155). This movement is akin to the parting of the genitals. Leach concludes:

It is two years since I have first brought up to my friend the idea that I might be losing my hair. I stand in the mirror and watch the shadows it makes as the sunlight shines through what remains and I feel only the awareness of sun shining in a place where there once was an opaque, medium sort of brown.

I sit in the orange chair of a beauty salon. My stylist is telling me not to worry. Women shed. Hair growth is a cycle. She tugs her fingers through my hair and catches a rough brown clump in her fist. “Although you do seem to be shedding more than normal.” She claps her hands over my ears. She’s not worried about me. She says I have a lot of hair left to lose.