Hard Work: Marilyn Minter at the Contemporary Arts Museum Houston

Charlie Tatum discusses labor and maintenance through the lens of Marilyn Minter's current retrospective in Houston.

Marilyn Minter, Blue Poles, 2007. Enamel on metal. Private Collection, Switzerland.

I’ve probably driven most of my roommates crazy taking too long in the bathroom. Even though I get up early, I somehow manage to fill up any extra time I have in the morning. The bathroom is a site of preparation—scrubbing, cleansing, toning, moisturizing, tweezing, trimming, swabbing, flossing, brushing, swishing, poking, prodding, looking.

This routine is what makes me feel presentable. For sales attendants, gallery assistants, publicists—those of us who sell things and ourselves—primping and beautifying are not spa luxuries, but rather work that we do every day in order to sustain ourselves and to function in our world. These little moments add up, and that labor is hardly recognized beyond an offhand compliment at a party. This work has been made essential, especially in our economy and especially for women and femme-identifying people. We’re expected to keep secret the fact that this is all a lot of work, time, and money. We didn’t wake up like this, Beyoncé. We’re never in a natural state of being—always mediated, always made up, always artificial.

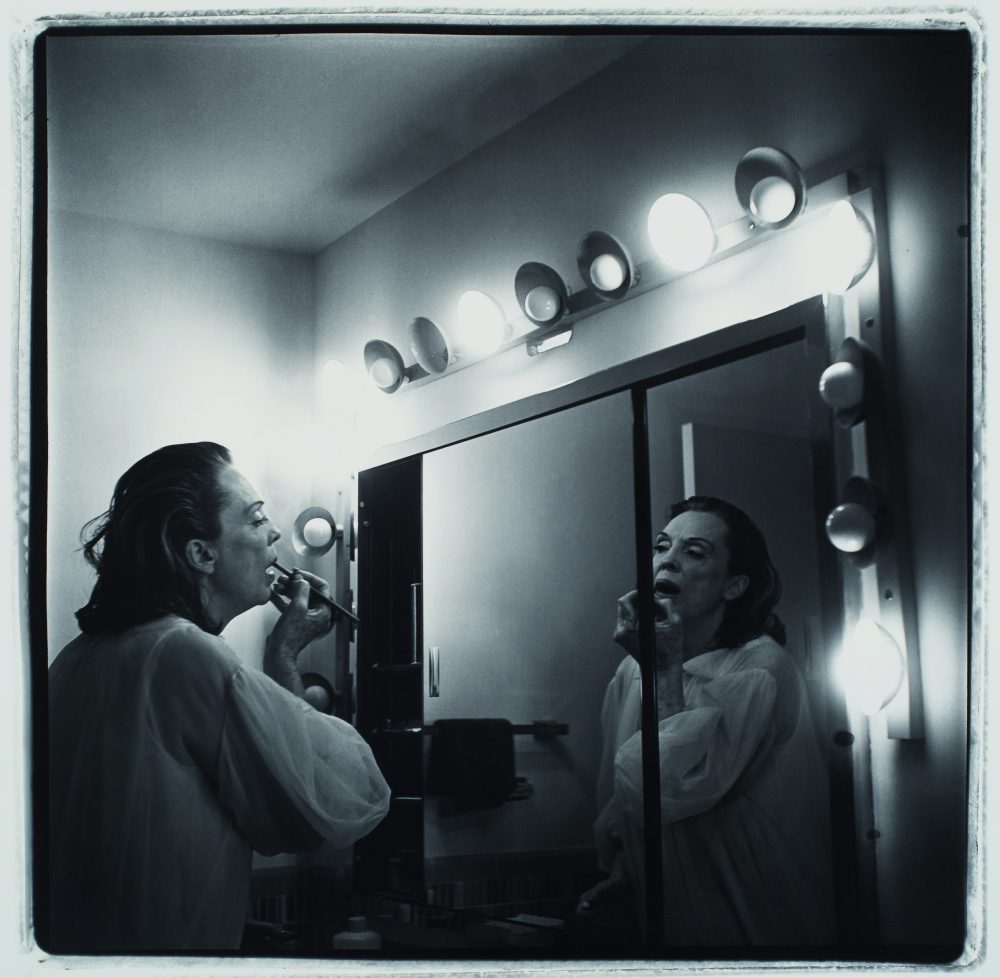

“Pretty/Dirty,” Marilyn Minter’s current retrospective at the Contemporary Arts Museum Houston, curated by Bill Arning and Elissa Auther, starts chronologically with a series of photographs from 1969 that Minter took while in school at the University of Florida, Gainsville. The pictures show her mother, a pill-popping, reclusive Southern belle, lounging disheveled among her belongings à la Grey Gardens (1974) or Hush...Hush, Sweet Charlotte (1964). She’s in various states of makeup. One photograph has her lounging in bed with curlers in her hair, surrounded by beauty products. In another, she smokes a cigarette (also in bed) as her nightie falls off her shoulder, her eyebrows perfectly arched. In Coral Ridge Towers (Mom Making Up), Minter’s mother appears as an ageing starlet, putting on lipstick in the bathroom mirror, half of the vanity’s lightbulbs exhausted. All of this labor is seemingly for nothing. She’s clearly not going anywhere.

Minter’s classmates were purportedly disgusted by the photographs, which give a sneak peek into the existence of a woman who seemingly failed to keep it together. Minter’s mother is not repulsive and the photographs aren’t particularly vulgar. Perhaps her classmates were responding to the shock of being forced to acknowledge the labor of maintaining one’s image in mid-century America.

Marilyn Minter, Coral Ridge Towers (Mom Making Up), 1969. Gelatin Silver print. Collection of Beth Rudin DeWoody.

In her “Manifesto for Maintenance Art, 1969! Proposal for an Exhibition, ‘CARE,’” Mierle Laderman Ukeles called to address all domestic maintenance:

Maintenance is a drag; it takes all the fucking time (lit.)

The mind boggles and chafes at the boredom.

The culture confers lousy status on maintenance jobs = minimum wages,

housewives = no pay.

clean your desk, wash the dishes, clean the floor, wash your clothes, wash your toes, change the baby’s diaper, finish the report, correct the typos, mend the fence, keep the customer happy, throw out the stinking garbage, watch out don’t put things in your nose, what shall I wear, I have no sox, pay your bills, don’t litter, save string, wash your hair, change the sheets, go to the store, I’m out of perfume, say it again—he doesn’t understand, seal it again—it leaks, go to work, this art is dusty, clear the table, call him again, flush the toilet, stay young.

Ukeles’s performances throughout the 1970s highlighted the forgotten labor of maintenance that has historically been relegated to women (the domestic) and to the working class (sanitation) by bringing these actions into the realm of art. In 1973, she washed the steps and floors of the Wadsworth Atheneum in Hartford, Connecticut, exposing the cultural expectation that women will tidy the messes in support of the largely white male arc of art history.

I am an artist. I am a woman. I am a wife. I am a mother (Random order).

I do a hell of a lot of washing, cleaning, cooking, renewing, supporting, preserving, etc. Also, (up to now separately) I “do” Art.

Now I will simply do these maintenance everyday things, and flush them up to consciousness, exhibit them, as Art.

After graduate school, around the time Ukeles was railing against expectations, Minter moved to New York. By this point, her practice had shifted from photography primarily to photorealist painting. A series of works on view at CAMH depicts the grid of the linoleum floor of her studio. A piece of plywood juts in from the top right corner. A coffee stain trickles diagonally. A scrap of aluminum foil and Minter’s source photographs are strewn across the composition. Sink Study, 1978, captures a failed meal: a block of frozen peas thawing in the sink and a cracked egg. Instead of getting on her hands and knees, Minter cleans the mess with her paintbrush. These works are technically pristine, her brushstrokes invisible. (Since 2000, Minter and her assistants have painted the top layer of enamel with their fingertips to further blur their brushstrokes.) Minter is displacing the work of domestic maintenance into the realm of artistic labor.

The artist’s 100 Food Porn series from a decade later depicts hands (usually a woman’s with red lacquered nails) handling and preparing foods, often phallic or vaginal in shape or association. Fingers shuck an oyster, slide down a cob of corn, split the head off a crawfish. These works are much messier than her earlier paintings, and they celebrate the sexual tactility of food preparation amidst a haze of faux-expressionist drips of paint that spew from perfectly plotted Ben-Day dots. This illusion of disorder, of mess, is carefully constructed, and these are moments where Minter wants us to see the process of image creation break down.

Minter is best known for her sexy, sumptuous paintings and photographs of models’ body parts, which she began in the early 2000s. These works capture flaws in the labor and production of beauty—seen in the form of primarily white, female bodies. Minter emphasizes that which would now normally be Photoshopped out: blemishes, the indentations of a sock’s elastic, a cluster of freckles, a missed swath of armpit stubble. Similarly, she’s sought out the grotesque by pushing luxury and perfection to its limits, staging elaborate photo shoots with models choking on pearls and beaded necklaces or spitting out globs of gold paint. Her 2009 video Green Pink Caviar—commissioned by Creative Time for broadcast on MTV’s Times Square billboard—shows tongues, lips, and hair sloshing around in a slimy mess of vodka, dye, and sugary cake decorations.

Marilyn Minter, Green Pink Caviar (Still), 2009. HD Digital video. Courtesy the artist; salon 94, New York; and Regen Projects, Los Angeles.

In 2014, Neville Wakefield, Playboy’s Creative Director of Special Projects, invited Minter to contribute to a special issue of the magazine featuring artist-designed photo spreads. In Minter’s submission, “Bring Back the Bush,” sharp pink, red, and gold nails run through sweaty, sticky pubic hair. The fingers stretch chains, flowers, and pantyhose across the models’ crotches. Ultimately, Playboy pulled the full editorial.

A simplistic reading of these works might lead one to think that Minter is merely critiquing the beauty and fashion industries, the impossible beauty standards they promote (white, thin, hairless, perfect skin, etc.), and the corresponding products they sell. But Minter’s work does more, reclaiming the production of beauty as a femme space, while still questioning the industries’ exploitative nature from within. (Minter has used commercial commissions with clients like Tom Ford and Playboy to underwrite her own expenses.) To label her work a non-nuanced denouncement of “capitalism” and “the beauty industry” would be too easy—for us, and for Minter—and would discount the ways the production of beauty—on television screens, in magazines, and in our mirrors—is an integral part of feminine identity in the modern world. Instead Minter uses everything to excess (color, lighting, makeup, products, editing), and ultimately leaves us with botched cyborg versions of the beauty standards so many of us are asked to uphold daily.

Marilyn Minter, Smash (Still), 2014. HD digital video. Courtesy the artist; Salon 94, New York; and Regen Projects, Los Angeles.

Editor's Note

“Marilyn Minter: Pretty/Dirty” is on view through August 2, 2015 at the Contemporary Arts Museum Houston (5216 Montrose Boulevard).