At the Table

Pelican Bomb staff member Noni Clemens shares her hair story shaped by her French upbringing and Zimbabwean ancestry.

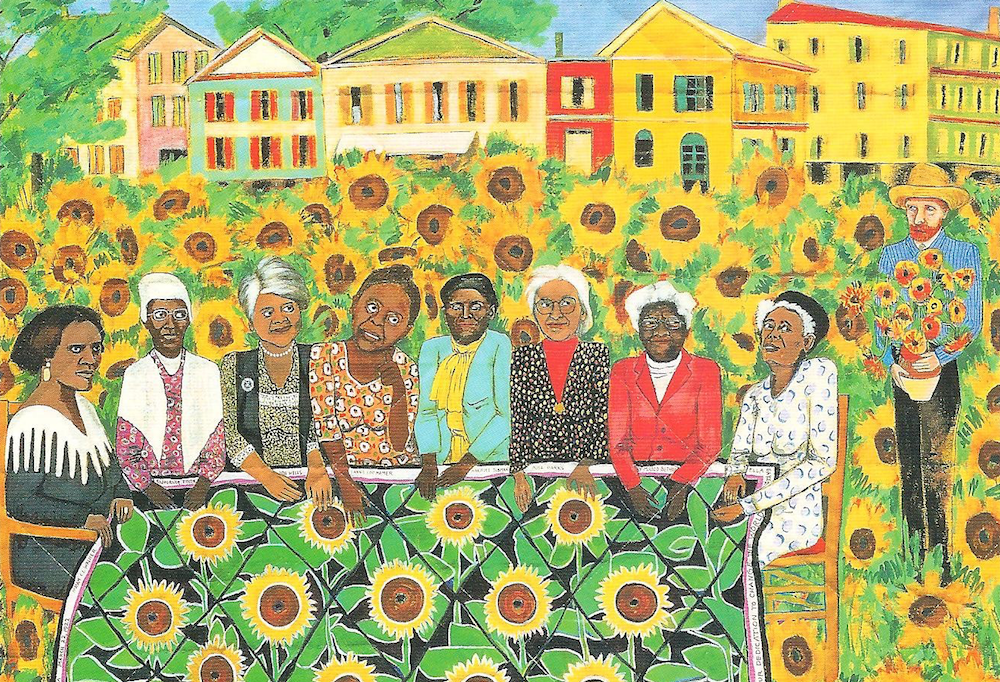

Faith Ringgold, The Sunflower Quilting Bee at Arles (Detail), 1991. Acrylic on canvas, tie-dyed, pieced fabric border. Courtesy faithringgold.com.

From the time I started growing hair until I was a pre-teen, my mother had the undesirable task of tending to my hair. She’d start by carefully and somewhat apprehensively laying out her tools, which always included a towel, a wide-tooth comb, and a container of Vaseline. The comb was used to tackle the seemingly endless masses of knots and tangles; the Vaseline to smooth out the baby hairs along my hairline and seal the end of my strands.

Performed every month or two (depending on the style I was rocking), this ritual served dual purposes. It helped my mother get organized and prepare for the at least two-hour barrage of crying, shrieking, tantrums, and later insults she had come to expect from me. It also signaled to my father and sister that a storm was coming and they best take shelter at the library, a friend’s house, or our finished attic—the farthest point in the house from the pop-up salon of horrors taking place in our living room. Obviously, I hated getting my hair done. Not only was it painful, it also made me feel small and isolated, like some rabid animal quarantined from the rest of the household.

I want to be clear that I love my hair. It’s big, somewhere in between curly and kinky, and there is a lot of it. I’ve been reminded of this fact by every hair stylist I’ve encountered in my adult life. My mother is not, nor has she ever been, a hair professional. She would have happily sent me to a hair stylist and saved herself the mental and physical exhaustion of our sessions, but that was never an option.

Until I was 12, we lived in Triel-sur-Seine, a quaint town of about 11,000 that is situated 25 miles northwest of Paris. Triel-sur-Seine was a great place to grow up in many ways: it was safe, quiet, and beautiful. My parents let me roam free most of the time I wasn’t in school and would send me out alone to run errands, when I would ride my bike really fast down a steep hill until I reached the eleventh-century gothic church that was the crown jewel of our town. Triel-sur-Seine had much to offer in terms of picturesque scenery and little by way of cultural and racial diversity. I was the little métisse girl in town, and it wasn’t until I was 10 or 11 that another non-white family—a large family from Mali—moved into our neighborhood and I had another black child as a playmate. All this to say that there was not a single salon in Triel-sur-Seine that knew what to do with my hair.

My mother caved only once and took me to Paris, to a hair salon run by West Africans. I don’t remember this well, but all you need to know is that there was a particularly widespread case of lice at my school. An embarrassment for all involved, it would be a long time until my next visit to a salon. From then on, it was just the two of us when it came time to do my hair. As I got older, the pain and the sitting became increasingly tolerable, and I came to appreciate our private hair moments. This was when my mother would tell me about her childhood in Zimbabwe, my birth country. She would try to teach me Ndebele, her native tongue, which I regrettably never bothered learning. She would tell me about her mother and her grandmothers, the strong and highly respected women who raised her in the absence of a father. They too, like me and like my mother, had their hair done at home by their mothers or aunts. She’d tell me that her dead grandmother sometimes visited her in her sleep to check on her or to help her through rough patches. She’d tell me that ancestor worship is common in Zimbabwe. The way Zimbabwean ancestors behave is not too dissimilar from Greek gods. They’re to be feared, as they are powerful and sometimes volatile. And like Greek gods, they sometimes step into the world of the living in disguise and without warning.

When I spoke to my mother about writing this piece, we’d never before unpacked our shared hair trauma. I asked her a number of questions in an attempt to learn more about the hair customs of the women who raised her, who now occupy seats at our ancestral table, in a land I haven’t seen in 24 years. I uncovered fascinating vignettes about my family’s history. I found out that my Gogo (Grandma) Joyce ran a popular speakeasy out of her house until 2001, just four years before her death, to supplement the income she earned as the head seamstress at the University of Zimbabwe. I realized that these moments of grooming I once thought of as an act of torture were, in fact, a point of connection to my heritage. I discovered that in those private moments with my mother, we were not alone. We were surrounded by the ancestors.