Love Is All We Need: "Of Many Colors" at Antenna Gallery

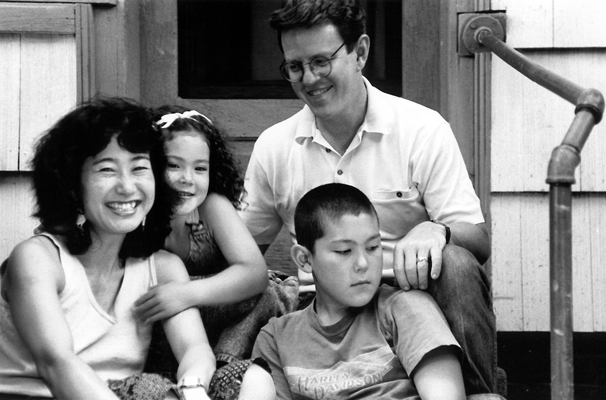

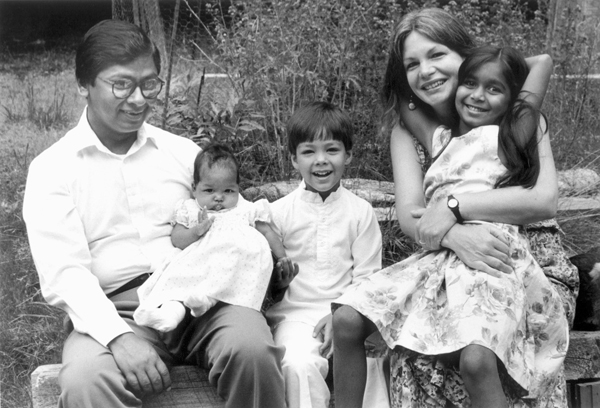

Portraits by Gigi Kaeser hang alongside interview transcriptions collected and edited by Peggy Gillespie in “Of Many Colors: Portraits of Multiracial Families” on view at Antenna Gallery in New Orleans.

Some names just seem to fit like a glove: the New Orleans Loving Festival, now in its fourth year, draws its name from the 1967 Supreme Court case of Loving v. Virginia, a suit brought by an interracial couple that ended race-based legal restrictions on marriage in the United States. Celebrating the many manifestations of love while at the same time exploring the complexity of identity in contemporary America, this year’s festival includes the traveling exhibition “Of Many Colors: Portraits of Multiracial Families” by Gigi Kaeser and Peggy Gillespie at Antenna Gallery. Quiet yet provocative, the installation contains nearly two dozen color and black-and-white prints of Kaeser’s photographs accompanied by interview transcriptions from a 1997 book on the topic, collected and edited by Gillespie. The photographs depict families of varying size, typically clustered together in warm, affectionate poses, shot both in domestic interiors and in public exterior settings.

Though the exhibition claims that it has a “great deal to teach about racial identity and racism,” its images rarely preach. What makes them so powerful, in fact, is their buoyancy: families laughing, talking, reading, playing, and hugging. Some of the portraits are of biological families, others of adoptive families, still more of long-term partnerships both with and without children, but one thing is common across them all: the care, joy, and love the individuals in these portraits all have for one another, irrespective of the color of their skin, the texture of their hair, or their ancestral roots. They are a striking contrast to the photographs of Ku Klux Klan rallies that belong to the exhibition “Mixed Messages.4” in the adjacent hall, evoking midcentury white supremacist fears of race mixing and “mongrelization,” even as the Kaeser photographs show the horrific consequences of such abominable acts: happy, smiling children, some of whom are even standing on their heads.

The portrait has long been a political genre used to codify power: take, for instance, official portraits of monarchs, intended to communicate the trappings of state authority and set a ruler apart from the people. Subtler but as strong are Kaeser’s photographs, which whisper rather than shout, indicating the opposite impulse. As Nathan Martin observed of the portraits of the Lovings themselves in last year’s festival, it’s not difference that is paramount in these images, but normalcy, illustrating a fact that many demagogues still don’t wish to embrace: that these portraits are the face of America today, as the country sees increasing numbers of interracial families and mixed-race children, including its own President.

Portraits by Gigi Kaeser hang alongside interview transcriptions collected and edited by Peggy Gillespie in “Of Many Colors: Portraits of Multiracial Families” on view at Antenna Gallery in New Orleans.

Though it is tempting to gaze into the faces of these families, the exhibition would not be complete without Gillespie’s accompanying text, and here one finds gems of insight—both of ongoing struggle and future promise—scattered throughout. Consider the report of a black mother assumed to be kidnapping her adopted white child by a mall security guard. Or the testimony of the children themselves, such as Patricia, a half-Cuban and half-Puerto Rican 18 year-old, who says that due to her mixed heritage, “I feel like I can’t be racist against any people.” Indeed, while this writer was in attendance, a white grandmother with her young brown grandson entered the gallery. The grandmother eagerly scrutinized the photographs, while the grandson scampered around the halls, unconcerned with portraiture and presumably even less with definitions of marriage. Running up to one observer in the room, with the pure un-self-consciousness of a child, he paused for a moment and said: “Let’s play a game.” What greater legacy could a country hope for in its youth?

These days, though debates about marriage no longer center on notions of race, it is important to remember that only a generation ago, it was possible for a child to be born to an illegal couple, both of whom were Americans. Such was the case with Natasha Tretheway, the nation’s most recent Poet Laureate, who has testified eloquently on her upbringing in the race-torn Deep South. What makes this exhibition so compelling is the expression of its position in the arts, not in argument: while portions of the text do serve to take a position, the vast majority of the persuasion—if it could be called that—is undertaken by the photographs themselves. And as the debate about marriage now blazes on other grounds, with decisions over its definition being rendered in state, circuit, and appellate courts seemingly every week, this exhibition is a reminder of how far in America that debate has come—and how far it still has to go.

Editor's Note

“Of Many Colors: Portraits of Multiracial Families” on view through July 1 at Antenna Gallery (3718 St. Claude Avenue) in New Orleans.