Civil Rights, Subtly: Grey Villet’s Photographs of the Loving Family

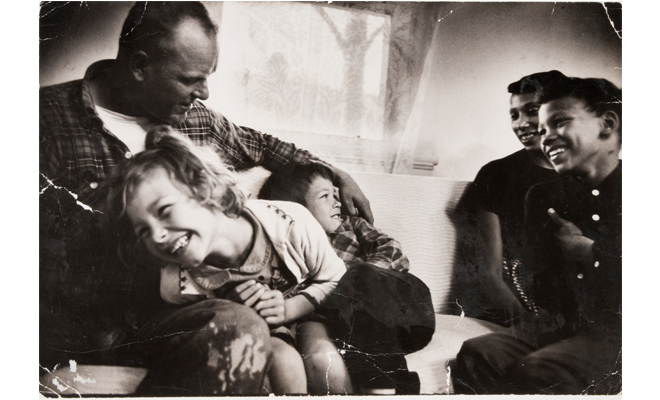

Photograph by Grey Villet of the Loving Family (Richard, Peggy, Donald, Sidney, and Mildred) in their living room, King and Queen County, Virginia, April 1965. Courtesy the Estate of Grey Villet and Stella Jones Gallery, New Orleans.

The popular documents of the Civil Rights Era are filled with virtuosic orators giving rousing speeches and protestors executing bold acts of public disobedience. The images show us wild confrontations between police and demonstrators and the bloody faces of black men and women in their aftermath. The lasting narrative that has rightfully subsumed the heroic acts and iconic incidents of the Civil Rights Movement permits little space for quiet lives like that of the Lovings. This is why you have likely never heard of them.

In 1958, after a county sheriff arrested the couple from their bed for violating Virginia’s law against interracial marriage, a judge sentenced Richard Loving, a white man, and his wife Mildred, a black and Native-American woman, to one year in prison. The judge offered to suspend their sentence on the condition that the couple remove themselves from the commonwealth for 25 years. Although the Lovings never considered themselves activists—they moved to D.C. after their conviction, but stayed home while Dr. King described his dream and watched him instead on TV—their actions involved them in one of the most important Supreme Court cases of the era. Loving v. Virginia resulted in the overturning of anti-miscegenation laws in 16 states and ended the prohibition of interracial marriage throughout the country. The Lovings declined to attend court on the day the justices were to read their decision. By that time, they were already clandestinely living back in Virginia. It was a longing for home, more than indignation, that prompted Mildred in the first place to write a letter about her plight to then-Attorney General Bobby Kennedy. He suggested she contact the American Civil Liberties Union, who took their case and won it. When Bernard Cohen, one of the Lovings' attorneys, asked Richard if he had a message he’d like conveyed to the court, Richard replied: “Mr. Cohen, tell the Court I love my wife, and it is just unfair that I can’t live with her in Virginia.”

Photograph by Grey Villet of Richard, Peggy, and Mildred Loving in their living room, King and Queen County, Virginia, April 1965. Courtesy the Estate of Grey Villet and Stella Jones Gallery, New Orleans.

An exhibition of photographs by Grey Villet is on display this month at Stella Jones Gallery as part of the New Orleans Loving Festival—named in honor of Richard and Mildred but with a fortuitous double entendre. They show the Lovings engaged in acts of historic sociopolitical consequence that look a whole lot like a couple of married folks just hanging around the house with their kids, kissing each other when the spirit moves them, being worried sometimes about this or that, and generally living a normal life. Taken out of context, the images depict a rough-skinned white man with a blonde crew cut obviously smitten over a relentlessly pretty woman of color who returns his affections. The pictures are tender and touching, and if a viewer was ignorant of the political clout and soft fortitude of the couple’s love-against-all-odds, one could appreciate them purely as exquisite snapshots of American life. They might seem—as many black-and-white images can tend to seem—like dispatches from a simpler time.

Villet took these photos while working on assignment for LIFE magazine in 1965, two years before the Loving v. Virginia decision. They have been exhibited only once before, last year at the International Center of Photography in New York. Barbara Villet, Grey’s widow since his death in 2000, wrote upon occasion of that exhibition that her husband eschewed any notion of capturing the political aspects of the Lovings’ situation and instead focused on what was most present: their love. “Quiet as a cat, he seemed almost to disappear as he worked,” Barbara wrote. “He avoided posing his subjects, refused to manipulate the action and simply waited patiently for telling moments to emerge.”

What we know about the Lovings makes it easy to imagine them allowing an outsider to disappear in their midst—they were people very much of their own world and intent to stay in it. Though they knew they needed to go to D.C. in order to wed, the Lovings maintained their unawareness that simply being married in Virginia was a crime. They had grown up in the same rural county, where the necessity for neighborliness often transcended race lines among the poor. Richard built their house, and with Mildred, their children, and some family and friends, they built a life. A recent documentary—The Loving Story, produced by HBO—shows Richard and Mildred just as immersed in each other as Villet’s photographs do, and shows the couple even more affixed to the intimate community of which they were a part. Had it not been for their arrest, Richard and Mildred Loving seem likely to have ridden out the Civil Rights Era without a fuss in King and Queen County, Virginia. Of course, history is riddled with these “had it not been for their arrest” stories, but such accounts almost always include a transformation of the characters involved—think of Malcolm X’s arrest, for instance. What’s remarkable about the Lovings is the degree to which they did not transform in the tumult. The immense, subtle strength that their resilience suggests is perhaps the most powerful element that Villet’s photographs, in their own understated ways, communicate.

My favorite photo in the exhibition was taken on a day at the track—Richard and two of his friends co-owned a 1963 Ford Galaxie 500 that they drag raced nearly every weekend. Richard is framed precisely in the center of the image, leaning on his trunk in a crisp white shirt rolled up at the sleeves, with a beer in his left hand and his right arm draped around Mildred. She’s wearing a smart checkered dress with its front unbuttoned to reveal a black blouse, and she’s smoking a cigarette. Friends flank them on both sides—though, from the resemblance, one of them must be Mildred’s sister—and from their vantage on the side of the road everyone is looking excitedly at something out of the frame, presumably, a pair of cars barreling toward them at great speeds. Rubber streaks run down the asphalt strip, which is lined with dense trees. The Lovings’ domestic life is left at home—the setting of most of Villet’s photos—and, unburdened by the court-related and other ordinary troubles that might afflict them there, Richard and Mildred look hip and at ease. While most of Villet’s images explicitly relay the fact that these two love each other, only this and other photos from the drag races hint at how they might have gotten together. Richard, a simple and often tired-looking construction worker at home, becomes the cool, confident guy who would attract the lovely, stylish, and (as is made clear in the documentary) intelligent Mildred, and his many black friends at the track show he disregards race in his social life and, thus, of course would be interested in such a girl.

But what I really love about the image is the way it elicits the strong nostalgia for the Golden Age of America that so-called classic pictures and films like American Graffiti (1973) are meant to instill in us—and often do, as long as we ignore inconvenient social facts of the era. The Lovings and their friends, here, have created a world we can fondly recall without ignorance—even if it was relegated to their isolated bubble in a small Virginia county. The great heavyweight champion Jack Johnson once said, “I have found no better way of avoiding race prejudice than to act with people of other races as if prejudice did not exist.” In this image, we see what Johnson’s prescription looks like, and it’s beautiful.

Photograph by Grey Villet of Mildred, Richard, and friends watching the races at Summerduck Dragway, Summerduck, Virginia, 1965. Courtesy the Estate of Grey Villet and Stella Jones Gallery, New Orleans.

Editor's Note

"Grey Villet: Loving Family Portraits" on view through June 30 at Stella Jones Gallery (201 St. Charles Avenue, Suite 132) in New Orleans. The exhibition is hosted by Stella Jones Gallery, the American Civil Liberties Union of Louisiana, and the Charitable Film Network in conjunction with the 3rd Annual New Orleans Loving Festival, a multiracial community celebration and film festival that challenges racial discrimination through outreach and education.