Back to Basics: Daniel Alley and Jane Cassidy

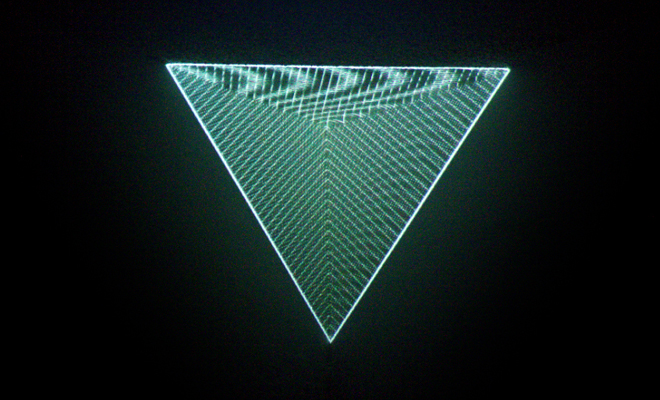

Jane Cassidy, They Upped Their Game After the Oranges, 2012. Projection mapping and stereo sound. Courtesy the artist and Parse Gallery, New Orleans.

How easy it is to take everything for granted: to go about our days letting the eye fall where it may, the ear collect only background noise, our thoughts bob aimlessly along like a cork upon the sea. And yet, everywhere we travel, each new step we take, the basic properties of the universe are at work: time, space, matter, light. Most of us learn what we need to know in school and then forget it, but how often do we pause to examine their continued effects on our lives?

Less often, surely, than is warranted. In their respective practices, artists Daniel Alley and Jane Cassidy each take these basic building blocks and measurements of the universe and retool them for a heightened awareness of the strangeness and the beauty of the world in which we live. These properties—seemingly arbitrary, infinitely complex, and yet elegantly woven together—serve not just as the subject but the medium for their individual explorations. By taking these known materials and building entirely new structures and objects out of them, Alley's and Cassidy’s works have the power to change the way we look not just at art but at the everyday world around us.

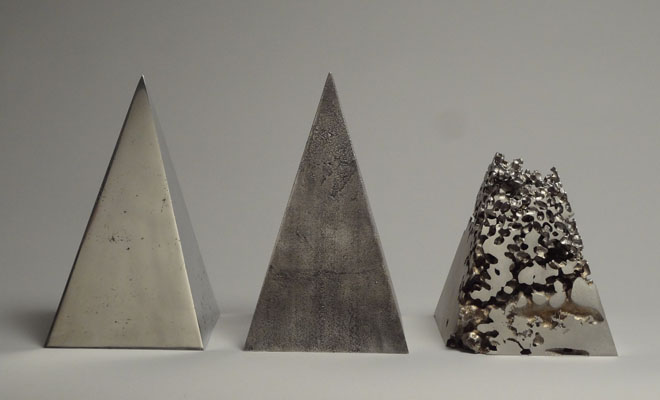

Alley, a sculptor and ceramicist originally from Alaska, has sought to redefine the notion of universal constants: measurements that exist independently of our observation of them (such as the distance light travels in one second) yet which, following their discovery and calculation, have set standards for quantification and sharpened our understanding of how the universe literally hangs together. Taking as his departure point the meter, a measurement which only in the last 200 years was precisely fixed—and even then, not without contention—Alley sees distance and space as essentially arbitrary. In order to establish our modern system of measurement, he suggests, we could just as easily have based the meter, or any other unit of common concordance, on another fundamental observation.

And so he has. In creating a series of like pieces, Alley has invented a new unit of measurement that he calls the moti, a Latin-inspired term invoking the distance light travels in one oscillation of a cesium atom: .032m. Crafting rulers that are ten moti long, which on the English system is a little more than a foot, he suggests that an entirely different scale for engineering and design is possible. Realizing this new measurement primarily in rulers of wood and glass, the decamoti, or 1 DAM Ruler, 2013, serves as the basis for other pieces as well: a trundle wheel, for instance, which Alley has hijacked and rebuilt to measure his unit instead of the foot, the numbers happily tripping up the gauge as it rolls across the floor.

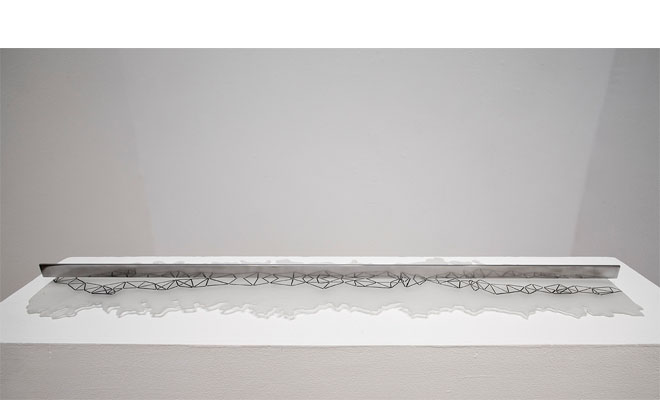

Daniel Alley, Metre des Archives, 2013. Glass and steel. Courtesy the artist.

While at first glance this enterprise may seem merely mischievous, it’s worth remembering that the history of measurement (and the history of science generally) is not without cost: the expense, difficulty, and danger of obtaining fundamental measurements and relations such as longitude, and the lengths to which researchers in centuries past have gone in search of common standards. Taking as his inspiration the seven-year journey by the French scientists Jean Baptiste Joseph Delambre and Pierre Méchain from Barcelona to Dunkirk, calculating the meridian arc of the earth, Alley has recreated their path on a large-scale glass work called Metre des Archives, 2013, recreating their triangulations onto its surface. The result, an irregular pale-blue plate with bubbles rippling through the glass, surrounding the precise geometrics of their path, memorializes their efforts and retells their story in a silent cartography.

If redefining space were not ambitious enough, Alley’s next project is to redefine time, crafting a pendulum clock (Peruvian Toise, 2013), a solar clock which uses focal lenses to burn the time of day into wooden panels, and a decimal clock based on a different universal constant. “Seconds don’t fit into the metric system,” he observes quietly, a statement that viewers who barely survived calculus would sooner not consider. But his overall pursuit—as he puts it, “to bring to conscious awareness aspects of our reality that are absolutely taken for granted every day”—finds companionship in the work of fellow Tulane MFA student Jane Cassidy.

Cassidy, a composer and multimedia artist originally from the Republic of Ireland, describes her project as “trying to give weight to light,” a project she has undertaken over the past several years with installations in countries around the world, of which four pieces are on display in New Orleans this month. In contrast to Alley’s physicality, however, and the heaps of iron and glass and wood piled in his studio, Cassidy pursues these fundamental materials from the opposite direction: through illusion, projection, suggestion, revelation, and ephemerality. Each of the pieces in her show “Swells for the Night Season” at Parse Gallery explores the nature and properties of light in different ways, marrying digital projections onto the gallery walls with Cassidy’s own musical scores, each composed to accompany its respective work.

Jane Cassidy, Out on a Limb, 2011/2012. Projection, stereo sound, and wire sculpture. Courtesy the artist and Parse Gallery, New Orleans.

Out on a Limb, 2011/2012, mounted in a small darkened space in the gallery, projects a series of concentric white circles through multiple layers of wire mesh—circles which grow and shrink in time with the notes of the composition. Based on a larger installation first staged in a bamboo grove at Art Farm Nebraska, the mesh, suspended in the middle of the room, encourages viewers to rotate and adjust it, smoothing and distorting the light and giving it a textured, almost grainy quality. They Upped Their Game After the Oranges, 2012, projects light onto an upper ceiling corner of the gallery, creating interlocking cubes and triangles that appear as three-dimensional objects, growing and shrinking almost like cancers inside one another in time with an ambient, but ominous, soundtrack. Light only these objects may be, it is difficult not to feel discomforted in their presence.

Following in the vein of Antony Gormley’s Blind Light, 2007, an enclosed room of fog in London’s Hayward Gallery in which viewers wandered blindly through the disorienting light, the possibilities of simple materials such as light, water, and sound to transform and destabilize the body are at the heart of Cassidy’s project. These transformations make Square Ball, 2011, and Purple Tinged Pearl Buttoned Bangled Billy, 2011, the most sustained and challenging of her works. (The two merge together in this exhibition, confined to a single room, their effects mingling.) Viewers enter a sealed-off space in the center of the gallery and face a projector approximately ten feet from its target wall. As the musical composition begins, the projector emits a single beam of light, which slowly develops into geometric forms: squares and hexagons and circles, divided into evenly-sized planes. As these forms begin to change shape and size, and rotate in smooth, calming circles, fog fills the room. The planes of light paradoxically create interior rooms of light within the darkened space, rooms which shift and adjust in accordance with the notes. But when the fog gives their walls weight and texture, the water vapor appearing as spiraling pools of liquid smoke, the effect is so real that one is tempted to run a hand along its surface.

That there is no actual surface—only that which is both created and revealed by the light in the same stroke—is part of the irony and the insight of Cassidy’s work. Viewers explore this box of light as if it were a tangible object, watching its growth and evolution into different forms, and eventually, a prismatic color wheel—in one sense, a kind of musical resolution from a minor to a major key. Stepping back out into the everyday world is a jarring experience, and healthily so: for what Cassidy shows us is that we on earth are all residents of a box of light, but that each day we inadvertently blind ourselves to seeing its richness and beauty. If only we would open our eyes, sharpen our sensibilities, and look more closely and more attentively not just at but with the light around us, we would see not just the objects or persons in our path but opportunities to know them afresh: to understand, as Lisel Mueller writes in the poem “Monet Refuses the Operation,” that “light becomes what it touches, / becomes water, lilies on water, / above and below water, / becomes lilac and mauve and yellow / and white and cerulean lamps…”

What are the universal constants in our lives? Light, weight, temperature, and gravity are but a few, but surely they are not enough to describe the whole of our existence, and even those which we agree on and enjoy are subject to redefinition from time to time. The consequence of Alley's and Cassidy’s work is that it asks us to pause and consider these constants anew: for re-evaluating those which exist in the world around us, all of which sustain our physical world and allow all creatures not just to exist but dwell within it, helps us to re-evaluate those qualities that dwell in the worlds within us: gratitude, compassion, mindfulness, humility, and attentiveness, those qualities that sustain our human world and allow us to live more fully in it. If we learn anything from the work of these two artists, it is that whatever universal constants do indeed exist, physics alone may not be enough to articulate them.

Daniel Alley, For William Frishmuth 'The point is received and is acceptable in every way,' 2013. Aluminum. Courtesy the artist.

Editor's Note

“Swells for the Night Season” by Jane Cassidy is on view until June 14 at Parse Gallery (134 Carondelet Street) in New Orleans.

Current works by Daniel Alley are available to view by appointment by emailing dalley1@tulane.edu.