Pratt Photography Lectures: Keith Calhoun and Chandra McCormick (Part 2)

Editor's Note

On December 5, 2012, Pelican Bomb was honored to be present as New Orleans photographers Keith Calhoun and Chandra McCormick shared their work at Pratt Institute in New York. This is Part 2 of the conversation between McCormick and Calhoun, in which they continue to share their work made post-Katrina.

It includes remarks from art historian and Assistant Professor of Contemporary Art at Pratt, Eva Díaz, who delivered a poetic response to Calhoun and McCormick’s work before opening up the floor to questions from the audience.

Keith Calhoun, Treme Community Center, 2010. Archival pigment print. Courtesy the artist.

Chandra McCormick: This is the beginning, I would say, of the restoration project—what we thought was a destruction of our work after Hurricane Katrina.

When we came back from Katrina, we found some of our photographs that we had exhibited. We had left them in a cabinet. They got waterlogged but they were beautiful. I had them wrapped and they were in a box. Many of you may know Mark Bradford. He’s an international artist. Well, he came down to New Orleans during Prospect.1 and he saw what we were doing and gave us a lot of support. He happened to see these images.

He asked, “What are y’all gonna do with these, Chandra?”

I said, “I don’t know what. I hate to throw them away. I really don’t want to throw them away.”

And he said, “Why don’t you hang them.”

Hang ’em? But we didn’t hesitate. We did what he said because I was like, “Mark Bradford said to hang them!” [Audience laughs]

We hung the pictures and it was a beautiful exhibition. The title of the exhibition was “Gone,” and it was all of the photographs that we thought were damaged imagery.

As we documented over the years, our passion was always black and white. We love the drama of black and white, but we would bring people pictures back in black and white and they’d be like, “Black and white? You don’t have any color?” So we started shooting color too. We also found there was a need for color with publications. When we were called by publications, they would almost always ask for color, so we started doubling ourselves. We would have two camera bodies each anyway, so we would have color transparency film in one and black and white in the other.

And this is the result of the Kodachrome color transparencies that were waterlogged. We didn’t know what to do with them but we didn’t want to throw them away either, so we put them all in a freezer. We gathered them and put them in garbage bags and Keith found a fridge on the street after the hurricane and we froze them.

Keith Calhoun: Don’t throw away that Kodachrome! [Audience laughs]

Keith Calhoun, Foots (left), from the Riverfront Faces series, and Ida Mae Strickland (right), from the Sugarcane series, both 2010. Archival pigment prints. Courtesy the artist.

CM: Even the black-and-white imagery on film has a certain mood. It has a lot of veins in it. Some of it looks like reticulation, if you know about film processing and your chemicals are too hot. It’s something you never wanted to see when you were shooting a job or something.

What I found with restoration is that a lot of the film had mold on it. The color shifted. Even in some instances the film cracked, so all of those things show up in these pictures.

This is an image from our Sugarcane series and her name is Ida Mae Strickland. She lived in a little town named Killona on the River Road. She was a retired sugarcane worker. You can’t tell here but she really had a hard time breathing. She had developed emphysema from working in the sugarcane fields. These photographs are part of a series called Pitch White.

Chandra McCormick, Freddy Hicks (left), Ernest 'All Night Shorty ' Evans (center), and Michael Knight (right), from the Heroes of the Storm series, all 2007. Archival pigment prints. Courtesy the artist.

CM: These three guys are three heroes whose names constantly came up when we were interviewing and talking with people after Katrina: Michael Knight, Freddy Hicks, “All Night Shorty” (his name is Ernest Evans). Shorty, the man in the middle, is actually the man who gave us the idea for the title Pitch White.

The men all knew each other. Before the hurricane they saw each other at the gas station or past each other’s houses. They started talking about what they were gonna do. They all had boats so they knew they we’re going to stay. They knew people were gonna need some help. So their conversation was, “Well, you better gas up.” That’s what they related to us.

When I talked to Shorty—the man in the middle, Mr. Evans—he said, “I gassed up my boat. I gassed up my truck. And I had a little bit of extra gas in some gas cans. My family didn’t want to leave me. I was trying to send them away and they said no.”

So he said they got all of the stuff they needed and they parked their truck at the Claiborne Bridge. They stayed there and they were just waiting. He said around four in the morning the rain was really bad. He said it was raining so hard that you couldn’t see anything. He said it was “pitch white.” That’s it! That’s how we developed that title. They saved so many people.

KC: Michael Knight and Freddy Hicks saved over 500 hundred people alone. Michael Knight salvages cars, so he took a bunch of boats that were abandoned by the St. Claude Bridge and tied them together. He made what we call a “Sea Train” like ya’ll’s subway here in New York. [Audience laughs] He hauled people out to the bridge for seven days. He and Freddy Hicks and “All Night Shorty” worked, so that’s why we titled it Heroes of the Storm.

CM: We also photographed Miss Josephine Butler. She’s 90 now but she was 82 going on 83 at that time. Deborah Sontag from the New York Times did a story on the Lower Ninth Ward families, specifically on Delery Street, which is one of the last streets in the Lower Ninth Ward of Orleans Parish. She interviewed Miss Butler—we call her Miss Phennie. Where she lived the water was so forceful that houses were knocked off of their foundations. The residents had a hard time coming back. The officials really didn’t want people coming back to the Lower Ninth Ward. Miss Phennie was a woman who was quoted in the New York Times as saying, “Before I let them take my property, I’ll chain myself to it.” I feel like she’s a hero. She’s the first person back on the block at 82 years old.

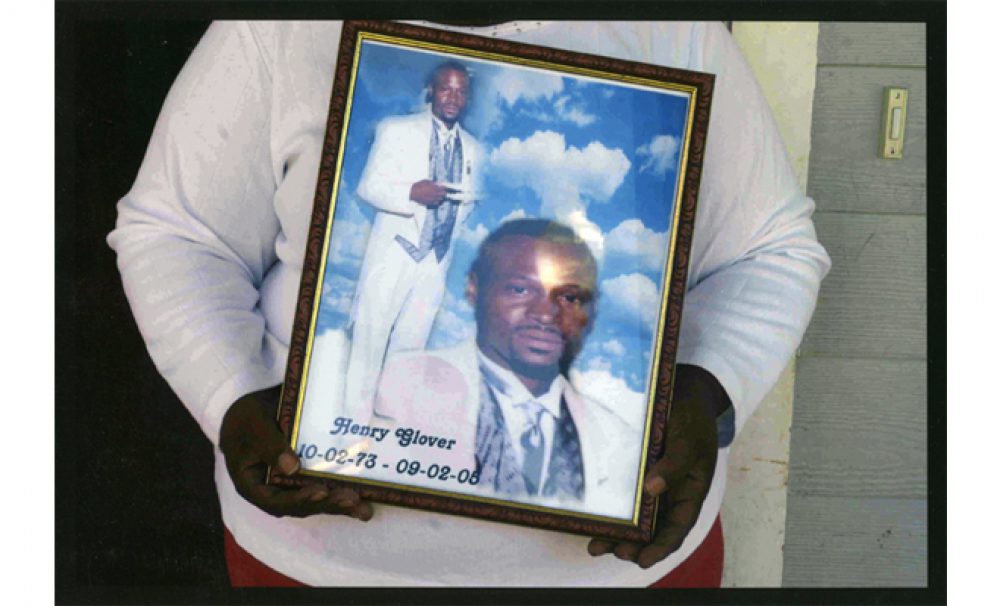

Chandra McCormick, In Memory of Henry Glover, from the Heroes of the Storm series, 2008. Archival pigment print. Courtesy the artist.

CM: William Tanner is the person who broke the story about a young man in New Orleans who had been victimized during Hurricane Katrina by police officers. Henry Glover was his name. Henry Glover was murdered by police. Henry had been shot. William Tanner, an innocent citizen passing by, saw this man on the ground, picked him up, and tried to get him some help. William Tanner had been bringing people to safety for the last couple of days, so when he stumbled upon Mr. Glover he put him in his car and he brought him to a facility. It was a sub-station that the police department had set up and they also had some type of medical staffing, so he was bringing Henry there when he was confronted by the police. When he went there he was trying to tell them what had happened. Tanner’s story is that they took him and another man—Henry Glover’s brother—and handcuffed them together. He kept saying, “There’s a man in the car and he’s shot. He’s shot.” Not only did the police let him die but they drove the car over the levee and torched it. They were just so negligent. They did not care.

KC: He was carjacked by the New Orleans Police Department. The police took the car with Henry Glover in it. They shot him and left the car behind the river. We were working on the story with A.C. Thompson who was the investigative reporter uncovering the story behind Henry Glover’s death. Just recently because of the story in the Nation magazine, the policeman was convicted of the murder.

CM: I took this photograph. This is Henry Glover. This is his mother, Miss Edna Glover, holding his picture. When we talked with A.C. Thompson, he was like, “She won’t take a picture.”

KC: She was scared.

CM: I understood that, but we talked to her and tried to convince her of the importance of actually taking the picture and putting Henry’s image out there; how impactful it would be in the case and everything they’re trying to do, so she allowed us to do this picture.

Eva Díaz: I’d like to think in a more global sense about photography and where we can situate Keith and Chandra’s work within the history of photography and within synchronous practices going on today. Photography has often been defined as a record of absence and the work we’ve seen today goes beyond what the important theorist of photography Roland Barthes claimed in his Camera Lucida was the ontological condition of the medium of photography, which is the fundamental pastness of each photograph, that the subject of any photograph is the passing of time, the imprint of a body on paper that will likely outlive its subject.

In Keith and Chandra’s work a multitude of absences are recorded: the gradual elimination by automation of farm labor on the plantations of upper Louisiana, the replacement of that agricultural economy with prisons, and the removal of mostly black men from urban spaces that such a relocation entails; the subtraction of emulsion on the surfaces of their works by the floodwaters of Katrina; the displacement and exclusion of certain populations from New Orleans today; and perhaps the greatest absence is the one that much social documentary photography aspires to record—justice or equality or retribution. Into these absences steps a vivid presence: those fighting individually, struggling for the right to return to New Orleans. Another presence: those who emerged as heroes of the storm; the presence of artists like Keith and Chandra who founded a space like L9 that represents a stakeholding in now vulnerable communities. It’s this paradox of presence and invisibility, of the eminent and immediate physical reality of the photograph particularly when we can see the water damage to the photographs that foregrounds this material reality and the paradox of that with the fugitive nature of social struggle. They are things that are always exceeding concrete representation, but for Keith and Chandra an “excess of documentary,” one could say as curator Okwui Enwezor once called a kind of practice of documentary today; it becomes its own kind of reality, its own kind of material reality, this excess of documentary.

Keith and Chandra have mentioned the importance of print publications to their work. Their work has been reproduced in the Nation and Harper's, and I also want us to think about L9 as an artist-run space that is a form of distribution that can link these often tendentious arguments about social justice with image making. The cultural theorist Edward Saïd once said that “culture works very effectively to make invisible and even impossible the actual affiliations that exist between the world of ideas and the world of scholarship” and art. We can think of Keith and Chandra’s documentary photography as a kind of research scholarship. One could say too that the linked distribution forms like the Nation, Harper's, and online publications have always been ideal venues for documentary photography for its multiplicity, much more than we can even think of the singular print circulating in the art gallery. I thought we could talk a little bit about the reach of photography today and think about these distribution forms and about Keith and Chandra’s L9.

Audience Member 1: I want to thank you guys for coming. I actually spent some time in New Orleans. It’s such a special city to me. I think what most people saw in the pictures is the sense of community that you guys really have. Listening to you tonight talk about the stories of these individuals that you are recalling, I’m just curious about your process. Are you guys just having one conversation or are you spending days within these communities? How do you guys work? How do you guys shoot?

KC: We shoot a lot of stuff. Now we’re working in Northeast Louisiana. We’re documenting for a whole year the demise of labor because a lot of these people are stuck out on back roads and these days with the fall of print journalism there’s not going to be much documentation, so we feel the need to go out and document it.

Everyday we can find unique pictures. We go out to second lines every Sunday they have a parade, but one thing about New Orleans every day there’s something going on with the culture. So it’s ongoing to document different things.

CM: We really do photograph something every day even neighborhood meetings. We go in and document those things—anything and everything . It’s like the American Express commercial, “Don’t leave home without it.” Well, that’s how we are with our cameras. [Audience laughs]

Audience Member 2: You don’t just take photographs, you also do interviews a lot when you’re working. In the 1930s the federal government supported people to do these kinds of projects. Do you think the government should be supporting this kind of work now?

KC: Definitely. I feel it is more needed now because at that time you did have labor. Now there’s no need for the labor. To show these people stuck out on back roads is real critical right now. They don’t have the means to come to the big city. Getting to the big city is not so easy now because in New Orleans they tore down all the projects. They really didn’t want the poor folk back and the same thing on River Road. A lot of these planters, they don’t have the need to have these workers living on their places any more. On most of these plantations they are tearing down the quarters and they’re planting more sugarcane and cotton.

CM: Machinery has taken over. And it is not just the projects in New Orleans, they tore down a lot of housing while people were displaced.

Deborah Willis: But the question is do you think the government…

CM and KC in unison: Yes!

KC: Government should step in now, should get some more involved photographers to take interest because I don’t see much documentation of the lifestyle of the people. You know, I was doing the same type of thing that the WPA did.

Audience Member 3: Do you think differently about images that maybe you take to share widely with an audience through publications as opposed to images that you maybe take to circulate within the community? Do you ever document just for the purposes of a community itself or does the same image serve both of those purposes? I’m curious whether you sometimes document or take images that you would only share with the community where you took the photograph.

CM: It’s a passion that we have to expose and to show. Even though some of the images we take are hard, it’s still beauty to me. It’s important that when we are allowed in people’s homes and communities to take pictures that we share with them what we do.

KC: Our work really belongs to the people. That’s why we set up in our neighborhood our own art space because there’s a need. A lot of people in our community they don’t go to the big museums and galleries, so we created a space in the neighborhood so we can engage and teach them the beauty. A lot of kids, they don’t see right across the street there’s an old lady been going to the church for 60 years and her life is there in that church. Teaching them to see that. Like out there on the River Road, I was fortunate to document those kids growing up on the river and now when I go back to that community it’s all gone, so the people who are still there they’re glad to see those images because that’s their grandparents, that’s their mama and daddy. So, it wouldn’t be right for us to take. Like now so many photographers come into New Orleans just to take and not giving it back.

CM: We’ve actually had people contact us since the hurricane and ask do we still have that photograph that we took of their mom or their family at a party or something.

KC: Like in the Lower Ninth Ward when I took that picture of a girl standing in the doorway, Carmelita, I just ran into her two weeks ago. She’s got like four kids now but to capture that moment 30 years ago not knowing that area would just be wiped out. We go to our neighborhood now, it’s all tall weeds and grass. You might see New Orleans French Quarter, but where we live at it’s still…

CM: The north side of the Ninth Ward community hasn’t really been rebuilt or developed like it should be at this point so there are a lot of families who are not back.

Audience Member 4: I’d like to know how you guys got started in photography. Who were your early influences or heroes?

CM: Well I actually got started with photography through Keith. A friend of mine introduced me to Keith because I wanted some pictures of myself, so I hired him to take my pictures. [Audience laughs] He printed all of my pictures except one and so he said, “Would you like to see how this is done?” And I said, “Sure!” So he brought me into his darkroom and he developed the last image that he owed me. I was fascinated and I asked him to teach me.

KC: Did you ever pay me?

CM: I really did. I paid you. I think I paid you too much! [Audience laughs] Anyway he taught me darkroom and the art of printing. I really enjoyed doing that because it’s so soothing. You get away from everything and you’re just there by yourself with your music and your pictures. Through printing his work, I developed an eye for composition. I would process his film and he’d be looking at it and I would ask, “Why is this wire going right here?” If you take a picture of a person and there’s a post behind them then it’s a distraction. That’s when he decided I needed to shoot.

KC: That’s the worst thing I ever did. [Audience laughs]

CM: He said, “You should shoot because you’re always critiquing my work.”

KC: A lot of times the person printing the photographs, they see all of the photographer’s mistakes. Most of our pictures, 99% of them, are full frame.

CM: We don’t crop.

KC: A lot of young photographers they don’t know the value of seeing things full frame.

Deborah Willis: Who are your influences?

KC: There’s a man named Clarence Smallwood in Los Angeles. He had a lot of influence. When I was young, I had a sister that sent for me to come to California to stay with her and she was sending me to school. She was very involved with a lot of activism, so she would tell me go to the LA County Museum. She would drop me off and leave me there. You know I didn’t want to be in no museum, so I would walk around the La Brea Tar Pits. She would come back at the end of the day and ask what did I see. I’d think this girl must be crazy, but then she would bring me the next week. And I went in for about two weeks and finally they had a meeting about blacks in film and there was a lady named Sue Booker who was speaking. After the talk I told her I was from New Orleans and asked if she could help me out with a job for the summer. A week later she called and hired me as a production intern at a TV station called KCET. From that point on it was cool because I was meeting a lot of photographers. Then I went back to New Orleans, met Chandra, and got stuck there.

Just being exposed, like with Chandra, just them days of being in the darkroom, it’s magical when you get in that darkroom sometime.

CM: As far as influences go, others photographers whom I admire: Gordon Parks, Dorothea Lange, Eudora Welty…

KC: Eugene Smith

CM: There are many others. Walker Evans. I like Cartier-Bresson.

Stephen Hilger: Keith, when you were in LA, in addition to the working for KCET, you were also working in some community workshops.

KC: At that time Los Angeles had a strong community. There were the Watts Prophets. There was the Inner City Cultural Theater. My sister got me involved. At the Watts Writers Workshop, I was able to hang with some guys called the Watts Prophets and they sort of took me in. I started taking pictures of them going around to the different performances.

CM: And they’re still friends too.

Eva Díaz: Can you talk a little bit about New Orleans art today? I mean it’s changed a lot after the hurricane. We were talking yesterday about some of the new spaces including your own which in many ways are a direct result of trying to rethink New Orleans as a cultural center around visual art, which was not really the cornerstone of how culture was seen in New Orleans before the hurricane. Food and music, yes, but it didn’t have as much of a rich contemporary art scene. You guys are part of the pre and post bridging…

KC: Now there’s a lot of new young artists coming in and the art scene has changed a lot compared to 20 years ago when they were all uptown. Now along the St. Claude area you got artists opening up their own space, having more control of showing their work. Galleries stay open now until about 12 o’ clock, so it’s a different energy now. There’s a lot of young artists coming and creating spaces, doing their work out of their spaces like we do at L9. We use our studio as an art center.

CM: I think the good thing about it is everyone who considers themselves an artist doesn’t have a gallery that represents them or someone to sell their work or help show their work. What’s being done is in home spaces and just storefront spaces that people are moving into and creating art spaces. So along the St. Claude corridor that Keith was speaking of, there are art openings every second Saturday. All of the galleries are open up along the St. Claude corridor and any galleries in the Lower Ninth Ward and in the Bywater. It’s a new movement of art and artists that are in the city now. I feel that sometimes the art community is not supported like it should be and instead it’s used. Now that there are more people who are expressing themselves through art, hopefully some of the city’s officials will understand how to support and appreciate it.

Stephen Hilger: You’re encouraging that support and appreciation and the activity of making art at L9. Can you tell us about the current show?

CM: We had the opportunity of working with some of the kids in our community in the Lower Ninth Ward this past year. We had an exhibition of their work. They ranged in age from 10 to 19 years old. We had about a dozen kids. They put together this exhibition with our help and all of the photographs were made in the Lower Ninth Ward. The name of the show is “ My Neighborhood Is Changing.” And that was inspired by a 13 year old who wrote a poem that became our text for the show. It’s 35 works from those kids and we recently had it up at the Arts Council of New Orleans and we’re going to hang it at L9 in January.

Audience Member 5: I’m sure you’re well aware that in the wake of Hurricane Sandy in New York and New Jersey artists also lost work in the onrushing water. What sort of advice would you have for them or what words of comfort would you have in light of their experience, which is in some ways similar to yours in New Orleans after Katrina?

CM: I would say don’t throw away anything until you fully look at it and decide what you want to do unless it’s not salvageable at all. All of this that we went through, we actually thought we had nothing and didn’t know what was on those slides. It just looked like dirt and specks and you saw yourself what the imagery was. Although we threw a lot of stuff away, I’m happy that the OSI offered us support and that we were funded by the Ford Foundation to restore our collection. I’m also happy that we decided not to throw it all away and we had the courage to challenge that restoration project because had we not done that we would have never found the beauty of these images.

KC: Artists gotta band together. This is a time when artists gotta stick together, put together shows, try to raise money, keep their spirits up, and work in collaboration. It’s still not easy. We’re still working in the freezer and we’ll be working for a long time.

Before (left): Keith Calhoun, St. Mark Baptist Church, Treme, c. 1993. Gelatin silver print. After (right): St. Mark Baptist Church, Treme, 2010. Archival pigment print. Courtesy the artist.

Editor's Note

Special thanks to Lambent Foundation for their generous support in bringing “Pratt Photography Lectures: Keith Calhoun and Chandra McCormick” to Pelican Bomb readers.