Pratt Photography Lectures: Keith Calhoun and Chandra McCormick

Editor's Note

On December 5, 2012, Pelican Bomb was honored to be present as New Orleans photographers Keith Calhoun and Chandra McCormick shared their work at Pratt Institute in New York. As part of the Pratt Photography Lectures, Calhoun and McCormick presented over 60 images, recounting the profound personal and communal significance of each of their photographs.

We’re thrilled to bring a selection of these images and their stories to Pelican Bomb readers, along with remarks by the evening’s panelists and questions from the audience. Pratt Photography Department Chair Stephen Hilger, who co-organized the event in conjunction with an exhibition at Lambent Foundation in New York, offers a brief prologue for our readers. Deborah Willis, the distinguished photographer and historian who has written most extensively on Calhoun and McCormick, introduced the duo that December evening.

We then share an abridged selection of McCormick and Calhoun’s photographs and stories drawn from the lecture, reflecting their extreme sensitivity, spontaneity, and humor as photographers and storytellers working together for over three decades.

Stephen Hilger: For more than 30 years Keith Calhoun and Chandra McCormick have chronicled the African-American experience in New Orleans neighborhoods and along Louisiana’s River Road. Their photographs celebrate the unique sense of place and community spirit that define life in the region. “Right to Return, River Road, NOLA Now!,” the exhibition on view at Lambent Foundation through January, frames the photographers’ oeuvre before and after Hurricane Katrina, in which the majority of their photographs were destroyed or dramatically altered. Calhoun and McCormick’s dedication to documenting vanishing traditions in Louisiana intensifies the loss of their pre-flood archive. The reclamation of their water-damaged pictures through a series of new images entitled Pitch White simultaneously represents their original subjects and the traumatic impact of the storm.

I first encountered Calhoun and McCormick at the L9 Center for the Arts, the community center that they run in the Lower Ninth Ward neighborhood of New Orleans, where they live and work. The walls of L9 were covered almost floor to ceiling with a collection of their photographs spanning decades of celebrations such as weddings, religious rituals, musical jam sessions, and second line brass band parades. I was struck then by the collective power of their images and by the photographers’ commitment to documenting, all the while participating in, the African-American experience in New Orleans. What also struck me was the condition of the photographs that had been muddied and damaged by the devastating floodwaters of Hurricane Katrina. Still Calhoun and McCormick proudly displayed the memories of what had been and they surge forward today.

Deborah Willis: It’s great to be here to celebrate, look, and re-look at the work of Chandra and Keith and think about their collaboration, which has taken many forms, all based in love and respect for family and community. Together they have photographed dockworkers, sugarcane workers and their families, and men incarcerated in prisons such as Louisiana’s Angola Prison. They’ve photographed Mardi Gras and second line dance, music, and foodways. Their work is about ritual and ritual is central to their work and also to making photographs. One of the aspects that we see is that their photographs look at the city of New Orleans as it’s preserved—the history through architecture, but also through love and through music, as well as cultural traditions. They’ve photographed businesses and churches and the activities of men, women, and children over the past 30 years. New Orleans is a place that is based in a unique setting. It is deeply involved with preservation and that’s something that Keith and Chandra have focused on for a number of years—preserving culture, memory, and considering the ideas of family.

Their photographs mediate between beauty and reflection. Beauty is a shifting narrative in their work and it’s not gendered. It’s found in the pose and the frame of their subjects—from brass bands to women enjoying music. Music is respected in the residents of the city of New Orleans. Their photographs are not passive. They are active and they animate. They record. They enlarge and make visible a likeness in the city. They attest to notions of a public consciousness. Their photographs transform us and transfix us as we consider ideas of death and also the celebration of life. Their photographs explore a cross section of New Orleans from Treme to the Lower Ninth Ward but also the museum district. They consider the aspects of narrative and symbolism and collective memory in their photographs. They’ve photographed in Armstrong Park, which is a fantastic place to think about and reflect on music. And they’ve also photographed the Treme district, which is a historical center.

They have focused on ways to reconsider the vibrant community, as well as the loss of the city after Katrina. They had to leave the city in 2005 and move to Houston. The media coverage of the storm had begun days earlier and the photographers decided to pack up their two sons, a niece, a brother, and a friend, and head west toward Texas believing that they would return home in a few days. Before leaving they placed their negatives, printed photographs, photographic equipment, and notebooks in several Rubbermaid bins and they stacked them high on tabletops and shelves thinking they would be preserved. They made the 19-hour journey to Houston where hundreds of families displaced by the hurricane had ended up at the George R. Brown Convention Center. There Calhoun and McCormick were stunned by the sight of rows and rows of cots of people sleeping and sharing moments. They met a few, talked about their experiences, and interviewed some of them. As a result they created a project documenting with one camera; asking questions, they felt they needed to make a difference and they needed to record the tragedy. They also noticed that the media and FEMA ignored many of the families at the Brown Center. They wanted a way to change and tell the story of this tragedy.

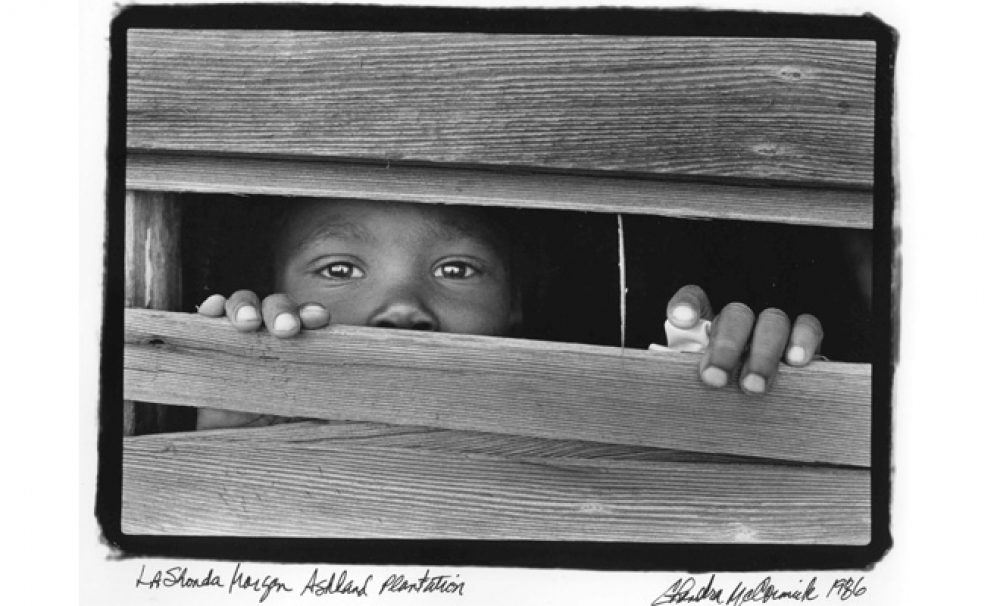

Chandra McCormick, LaShonda Morgan, Ashland Plantation, 1986. Silver gelatin print. Courtesy the artist.

Chandra McCormick: This is a photograph that was taken along the River Road. It’s from a particular essay on sugarcane workers. Soybean and sugarcane were among the largest crops in these communities for work.

This is a little girl in Port Allen on Ashland Plantation and her name is LaShonda Morgan. I took this photograph because we were photographing the quarters where the workers and their families lived. This is actually this little girl’s house. It’s not a fence. It’s her house and the wood was missing. It was wintertime and she was peeking out through the weatherboard. I wanted to show that. It’s artful, but it’s also sad because we know that house was cold.

Keith Calhoun: In the early 1980s, me and Chandra decided to document the last working class people along the River Road that was left behind. Families have been living on the same plantation for more than 100 years. We wanted to record the demise of labor because now technology is changing and machinery has taken over the labor force, so we wanted to capture some of the workers who still live on the River Road.

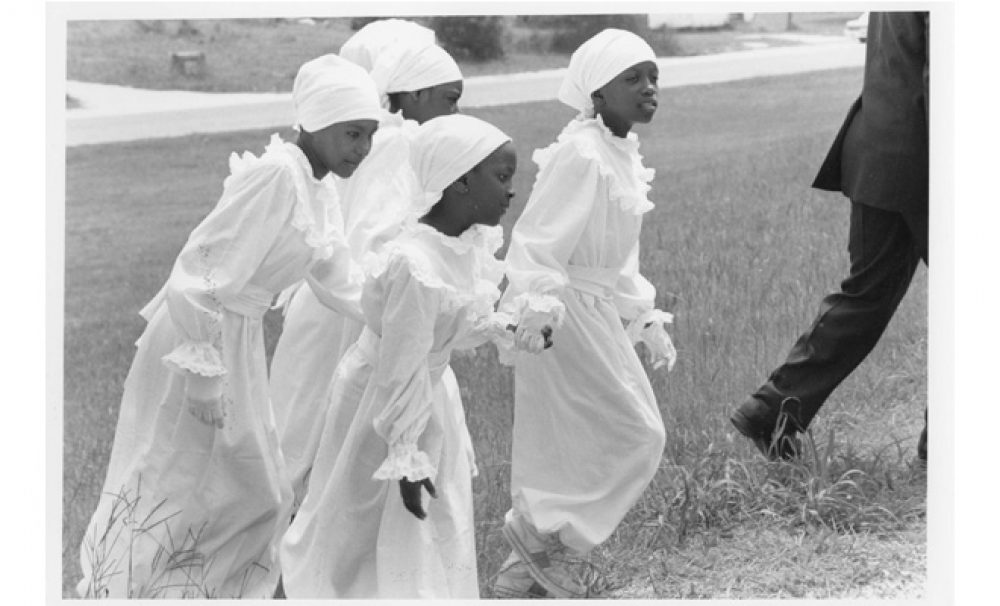

Keith Calhoun, Going to the River, from the River Road series, 1986. Gelatin silver print. Courtesy the artist.

KC: Me and Chandra document a lot of the river parishes and we wanted to capture some of the old churches along the river because so much history is buried in those churches where people have been worshipping for a long time. These kids are going to the river.

CM: The girls are baptismal candidates.

KC: We just started re-documenting the community where this picture was taken. It’s called Phoenix, Louisiana. I think they had 30 feet of water so we’re honored that we were able to document that community before Hurricane Katrina. Members of the community are now asking us for some of the pictures that we had taken during that time.

CM: This community is also one of the communities where they had African-American fishermen who were very much impacted by the BP oil spill.

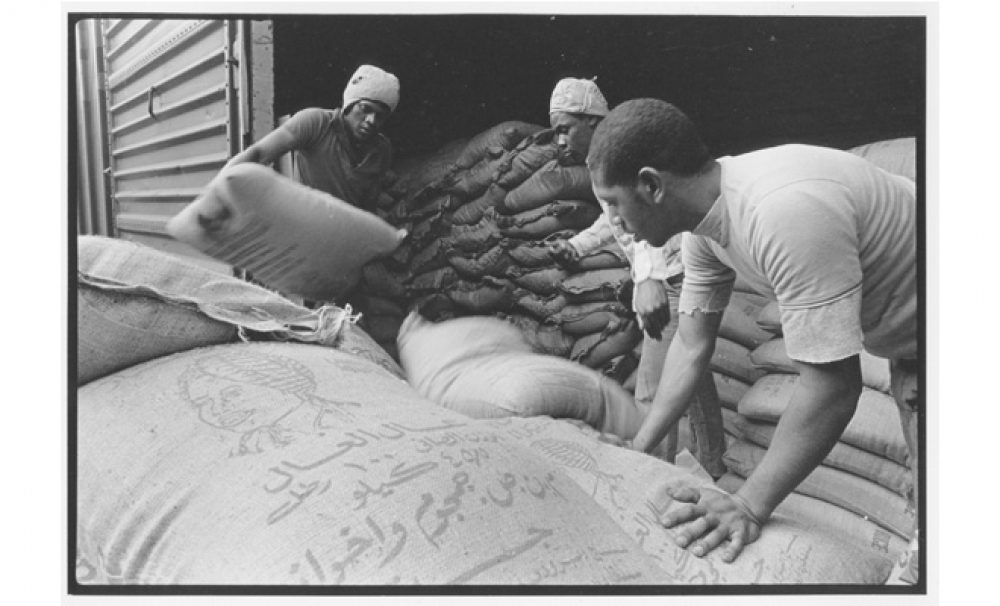

Keith Calhoun, Freight Handlers, from the Riverfront Faces series, 1980. Gelatin silver print. Courtesy the artist.

CM: The dockworkers is a photo essay by Keith, so he can probably tell you more about it.

KC: Again so much has changed with the labor force, the containerization of cargo versus actual men doing physical labor. I wanted to document the last men of the docks because my father was a dockworker. As a boy, I always remember him coming home with dust and smut all over him. As I got older, I went out there on the river with a camera and I was fascinated seeing the work that the men were doing, so we couldn’t help but want to capture that moment.

CM: Those are 100-pound coffee sacks.

KC: When I met Chandra she was working on the docks. [Audience laughs]

CM: That’s true! Keith is a jokester, but that is true. I was a clerk on the river and I used to count out the cargo that the men unloaded or loaded to be shipped.

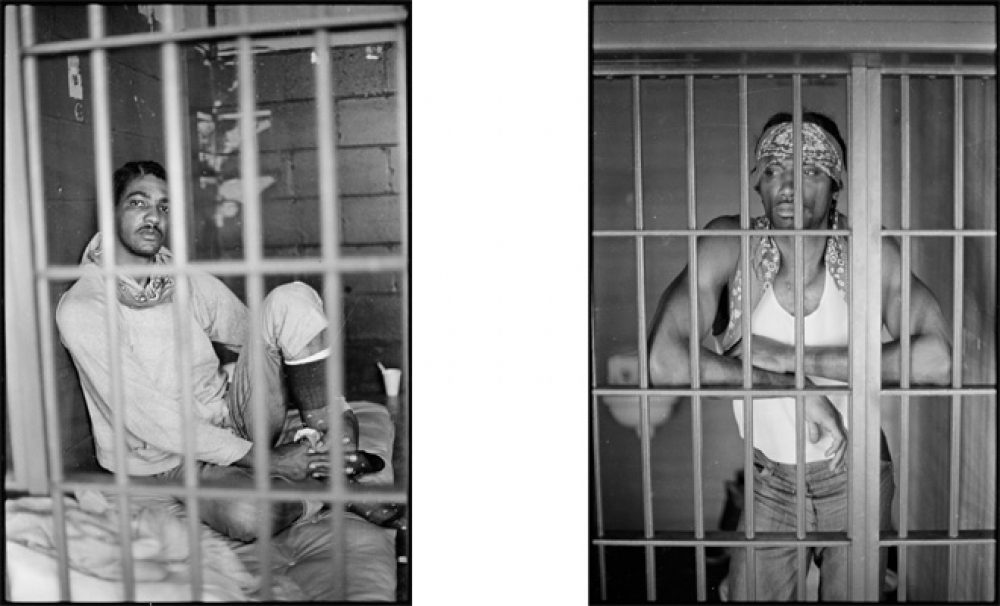

Keith Calhoun, both titled Lockdown, from the Angola series, c. 1980. Gelatin silver prints. Courtesy the artist.

CM: These photographs are from the Angola Prison series. We have a lot of photographs just of the incarcerated men, but this project became something more. As we documented people who were incarcerated and knew some people who were incarcerated, we saw the effects that had on their family members. When a loved one is behind bars, the family outside is dealing with the pressures that loved one is facing. It’s a feeling of being incarcerated too in so many ways. The series was about the literal incarceration of the men but it was also about the effects that incarceration has on families and how children deal mentally with members of their family that are incarcerated.

KC: This is Glen Demorell. [Man pictured left]

CM: This is a man—I’m sorry, Keith, but I don’t know if you would have said—this is a man that Keith documented through the process in the Angola series. Glen’s mother died while he was incarcerated and Keith documented him at his mom’s funeral. Glen is now out. He’s an upstanding citizen. He’s a foreman on his job. So Keith followed him from prison back home.

KC: Angola today is really hard to get in with a camera–harder than when I went. Even at that time, it was hard to get in lockdown—what they call CCR [Closed Cell Restricted] lockdown. The inmates are in lockdown 23 hours a day and get 1 hour out the cell. The free people didn’t want me to go, meaning the people running the prison. They were saying it was too detrimental for me to go inside. I told them, “Let me take my chances.”

I didn’t use a flash. I was shooting natural light, and it was nice to capture those moments.

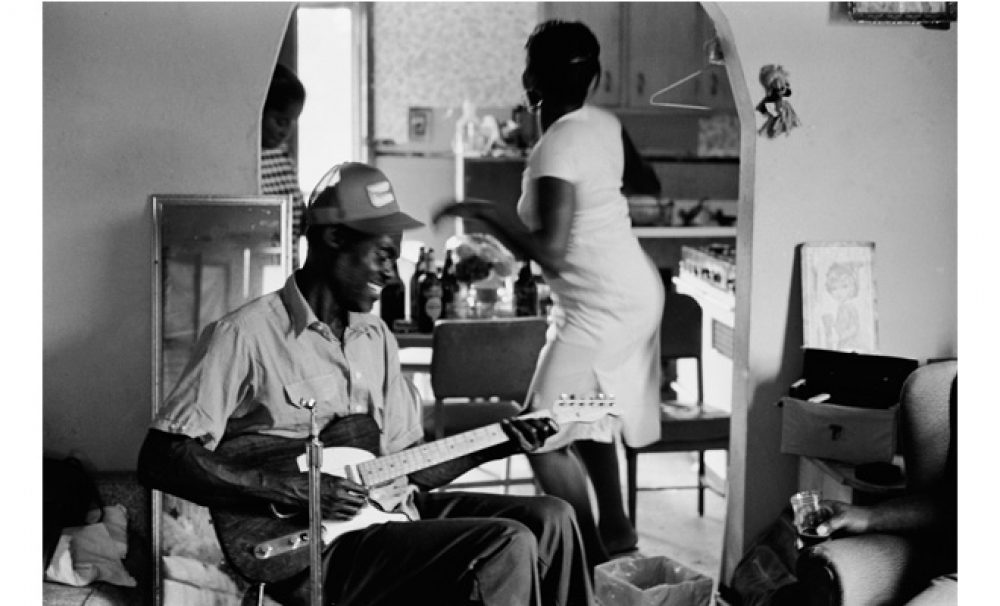

Keith Calhoun, Saturday Night Fish Fry, c. 1980. Silver gelatin print. Courtesy the artist.

KC: At one time in the Lower Ninth Ward just about any Friday or Saturday you could go to someone’s house for what we call fish frys. People had suppers, cooked food, got together, played music.

CM: We had a local musician in the Lower Ninth Ward who became pretty well known—a blues singer. His name was Bill Webb. Boogie was his nickname. This is a picture in his house. They would get together and jam, you know. The man playing the guitar, his name is Ozzo. He’s a friend of Boogie Bill’s. The lady in the white dress is Grace, Boogie Bill’s wife. Then you see in the back a woman who is kind of peering through—she and Grace were dancing. She’s got a striped shirt on, that’s Ozzo’s wife. And then all the way over here, this hand coming out, that’s Boogie Bill with his drink in his hand. [Audience laughs]

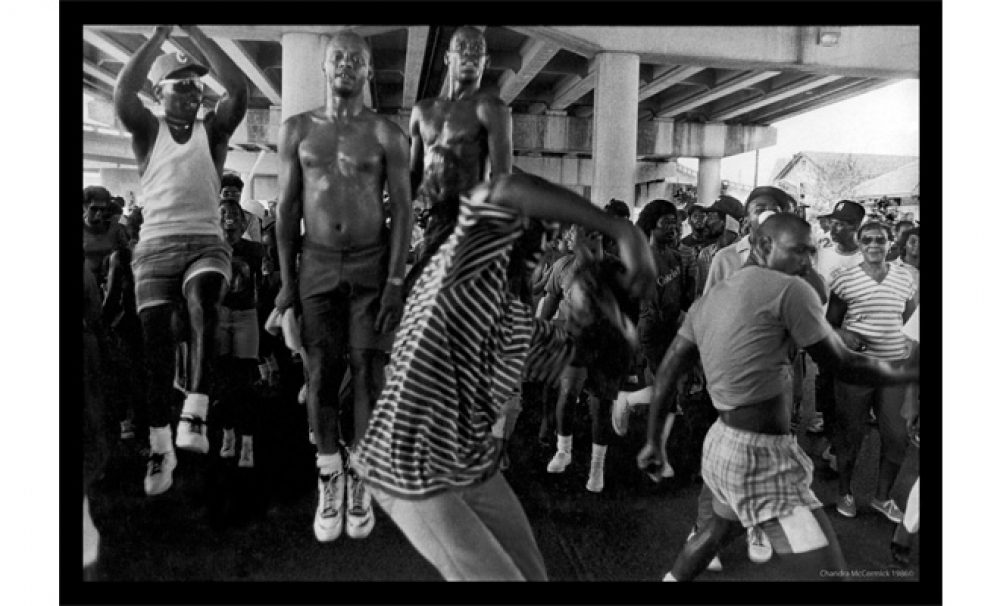

Chandra McCormick, Ascension, 1988. Gelatin silver print. Courtesy the artist.

CM: This is at one of the second lines in New Orleans. There are many social aid and pleasure clubs in New Orleans and just about any and every Sunday there’s usually a parade because there are so many clubs. We photograph the parades and we like taking pictures of the musicians. We photograph what we call sidelines—people on the side watching as we go by. It’s a great way to see the neighborhood.

This is a photograph that I took. The five guys that you see belong to a club called the Furious Five. I used to love to watch them dance because they all danced together. They did this spring up thing. There’s a tempo in the music and sometimes all five of them would be up in the air like that so I always said, “We gotta get that shot,” and I really love this one. It also reminds me of the Maasai warriors in Africa that do the same thing.

Editor's Note

Part 2 continues with McCormick and Calhoun’s photographs post-Katrina.