Lost Rites: An Interview with Stephen Collier

Stephen Collier, Helter Skelter Artifact, 2011. Acrylic and ink on fiberglass and resin. Courtesy the artist and Jonathan Ferrara Gallery, New Orleans.

Editor's Note

Stephen Collier and I met twice to get all this on tape. The first attempt was a late night at the AllWays Lounge on St. Claude but a rockabilly band in the next room made the recording mostly useless. At a certain point we stopped worrying about it and just talked music.

It was for the best because I found myself a little disarmed at how straightforwardly Collier talked about behavioral psychology, David Cronenberg, violence and its manifestation in pop culture, childhood memories, carnival masking, and amateur archeology—all in the service of his art. Psychology is a catalyst for Collier’s work: interior states and their violent, repressed, weird, or unrecognizable exteriorizations have surfaced since he began showing art in the early 2000s. They’re also the impulse behind a new series of painting/sculpture hybrids based on Mardi Gras masks and the images law enforcement officials use for target practice that he’ll show for the first time at the Acadiana Center for the Arts in Lafayette.

Collier is a founding member of Good Children in New Orleans. In 2011, I curated an exhibition at the gallery that included work by each member of the collective. Collier made a new piece, Amalgamation, a scattering of mystical, cultish-seeming objects set against a battered hunk of cardboard drowning in patchouli oil. Its centerpiece: a big, glossy bubblegum-pink plank of fiberglass whose surface was scarred with hermetic doodles and scribbling. The plank, Helter Skelter Artifact, is a faithful replica of the famous door found at Manson’s Spahn Ranch, the one with the peace sign, “NOTHINGNESS,” “HELTER SCELTER,” and, eerily, “ALL GOOD CHILDREN” scrawled nastily across it.

Collier created the installation Club Helter Skelter for Manifest Exhibitions in Chicago in 2011, and the press release quoted Manson. The beautiful and disturbing passage pertains to most of his work:

Have you ever seen the coyote in the desert? Watching, tuned in, completely aware. Christ on the cross, the coyote in the desert — it’s the same thing, man. The coyote is beautiful. He moves through the desert delicately, aware of everything, looking around. He hears every sound, smells every smell, sees everything that moves. He’s in a state of total paranoia, and total paranoia is total awareness.

— Nick Stillman

Nick Stillman: Where’d you grow up?

Stephen Collier: I was a Navy brat, born in Biloxi on a base. Moved to D.C., started kindergarten, and then to Hawaii until I was 12. Then my father retired from the Navy, so back to Biloxi briefly, then his hometown in Natchitoches, Louisiana.

NS: Being a military kid would have seriously stressed me out. My mom wanted to move from the tiny town I grew up in when I was maybe 10 and I freaked. We stayed.

SC: As a kid, you get used to it. There’s a new set of kids you become friends with, then you move, so you learn how to socialize. And when you move to a small town in the Deep South, you have to learn how to fight. I looked a little different. I’m half Vietnamese.

NS: Didn’t kids think Hawaiians were cool?

SC: I was just a new kid in a new place; I think it happens to everyone. The first person I got into a light brawl with ended up being one of my best friends. That’s how it is.

NS: How did you end up in New Orleans?

SC: I transferred to UNO for my senior year from LSU and before that Northwestern State University. I was a psychology major. I took a photo class with Tom Whitworth and it just changed the way I saw things. I really fell in love with the idea of art. The process of making art was much different from psychology.

NS: And of course, you were almost done with college.

SC: So I had to pretty much start over. Three years later, I graduated. Here I am, still in New Orleans.

NS: What was the art situation in New Orleans like at that time? This is when?

SC: I graduated in 2000 and even after that, it was just a small group of artists making like-minded work. Most of the galleries weren’t really interested, so one way to show was to find spaces for one night and throw a party.

NS: In the Bywater?

SC: It was wherever you could get space: uptown, downtown, the Bywater. There was a place called the Pickery, a warehouse really close to the Convention Center. These guys I was in art school with bought the building and when they graduated, they started having shows there. A lot of people came to those one-night shows. Then the city ended up annexing the building because they wanted to build a parking lot for the Convention Center. It’s still just a field there now.

NS: Did New Orleans feel like a city artists were trying to stay in or trying to leave?

SC: I don’t think anyone was thinking about it. We were just thinking about work and were all here at the same time. Some galleries would give us a space for a month if we talked them into it. Some of those artists at the time were Srdjan Loncar; Dan Tague; Generic Art Solutions, which is Matt Vis and Tony Campbell; Jessica Goldfinch; Jonathan Traviesa; and Christopher Saucedo, to name a few. A lot of us knew each other through UNO and ended up back in New Orleans after Katrina.

After Katrina I went to New York and did a residency for a year at the LMCC. After that, I felt like I wanted to come home and do something to help rebuild the city. I started looking for a space with a friend and realized that Tony and some other people were looking for a space as well and we all just pitched in and formed Good Children in 2008. Now we’re in our fifth year.

NS: New Orleans is on the world’s radar for a lot of reasons, but I don’t think it was on the world’s radar for contemporary art until really recently.

SC: Not at all.

NS: Talk about how New Orleans has changed as an art city.

SC: It’s nice that young people are moving here; for a while people were getting educated and leaving. Now people are graduating and staying. There are a lot of artists and art professionals coming here straight from art school. It’s nice to have this new energy. It seems like every month you hear of a new art space or organization opening. It’s refreshing. Before the storm, there wasn’t a huge young population here like there is now.

NS: It seems like it would be easy to harken back to the good old days when New Orleans had no pretense of having an “art scene.”

SC: It’s for the better now. One, you have a bigger audience. We were pretty much just showing to ourselves before. A bigger audience is always good for your work.

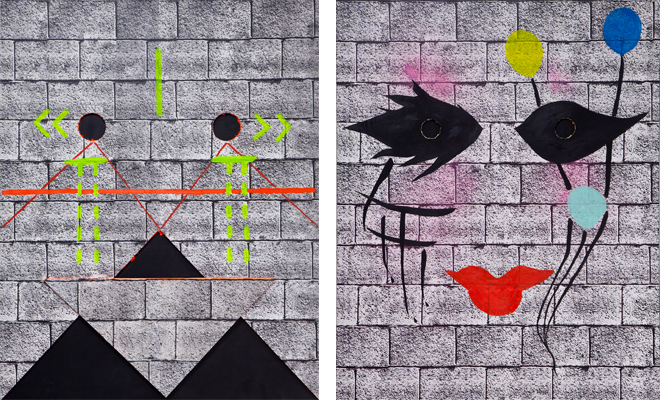

Stephen Collier, Man With Crystals, 2011 (left) and Puppy Love, 2010 (right). Both inkjet on archival paper. Courtesy the artist.

NS: Let’s talk about your work. I want to begin with Amalgamation, a piece you showed in the "Hit/Refresh, Volume 1" group show at Good Children in late 2011 that I curated. We had talked through a few ideas for what you might do, but I was unprepared for a piece that manifested such an intensely dark energy.

SC: I was born towards the end of the Vietnam War, a time of intense conflict. The hippie movement was winding down. I was just starting to see these things in the media. Manson’s story was being turned into made-for-TV movies; he was becoming pop culture. Later in the ’70s there was also the Jonestown Massacre. As a kid, you don’t really understand it, but it’s there and it’s frightening. There’s a mysterious aspect. I’m sure if I were older when that stuff came out, I’d have a different attitude toward it.

NS: Or younger. I didn’t know who Manson was until I was maybe a teenager. There were older guys at my school who wore denim jackets with studs in the back, kind of a ragtag gang, and they were more interested in scaring younger kids on the bus with stories about playing Ozzy records backward to find satanic orders. Manson would have been right up their alley, but this was before my town had cable TV, so maybe they just didn’t have that information yet.

SC: These would have been the same people I hung out with, the people who listened to good music. I hung out with everybody though. It was a small town. Anyway, Amalgamation consisted of a wall that was patchworked with cardboard, and I slung patchouli oil on top of the cardboard, almost in a Jackson Pollock sort of way, which got me in trouble with some of the other artists showing in the space… smell can evoke memories and responses almost instantaneously. On top of the cardboard were objects I had made, assemblages and things like a replica of the famous graffiti door at Spahn Ranch. There were dreamcatchers splattered with paint that were also burnt with a torch. I wanted to give them a feeling like they had gone through the ringer of bad energy. There was a ceramic club on the ground. I wanted to make this environment that had mystery lingering in it, almost like it was sacred and personal. And a feeling that it is this last resort for happiness… a means to something else.

NS: It seems like splattering and scattering were both of interest at the time.

SC: The use of cardboard as a wall and the splatters were references to the temporariness of a psychological state. After time, the oil stains on the cardboard, and the smell, will dry up and diminish. The way the patchouli oil was applied was somewhat violent. Normally, patchouli is associated with peace, love, and drug use. The other objects were meant to be rearranged periodically throughout the exhibition. I wanted the environment to seem haphazard and have a sense of something in transition.

NS: Manson is probably the most obvious example, but the American people and incidents that stand in for societal disorders or psychoses are everywhere in your work. Let’s talk about that as it relates to some different pieces, starting with the Group Activity video.

SC: With Group Activity I was interested in this idea of a group where at first people have good intentions but the dynamics shift and things go wrong, especially when you have psychotics or sociopaths as the driving forces. I’m not really interested in cult leaders per se; I’m more interested in the group and how people ended up there. Which explains these candles [Collier produces two objects cast in aluminum, one a hooded witch-like figure, the other a vertical cluster with a heart shape as its base]. These are spell candles that you get at the local botanical shop. People buy them to cast spells that might better their lives. I wonder how many of these were used in acts of desperation. The couple on the heart is the love candle; the witch exits bad spirits. All these candles now are mass-produced in China.

When I was younger, I was in a park with a bunch of other kids, throwing and breaking beer bottles. There were so many bottles lying around and we were having so much fun that I didn’t realize we were doing something wrong until the police arrived. I ran away and hid. When I got home, the police were at the house and we had to go back and clean up the glass. Group Activity is almost a reenactment of that memory. I recruited several people, we broke glass bottles on the wall inside of Good Children, and took the shards and did something constructive, making these jagged, sharp objects that are glued together centerpieces—very brittle ones. Group dynamics can be fragile.

NS: What about some of the pieces that have an undercurrent of violence, but also have this pathetic quality, like the Situational Targets where someone is pointing a gun at you, but a bunch of puppies or something similarly absurd replaces the gun?

SC: Shooting ranges and the security and law enforcement industries use those posters for target practice. The posters have images of figures confronting the viewer with guns and other weapons. I wanted to change the meaning of those images. So I collaged different images and objects on top of the weapons—cakes that say “BFF,” roses, more mystical objects like crystals and dreamcatchers—and rephotographed them. The objects are overlaid kind of sloppily on top of the weapons; I wanted to make those gun-pointing figures endearing.

Stephen Collier, Purification Clubs, 2010-11. Glaze on ceramics. Courtesy the artist and Jonathan Ferrara Gallery, New Orleans.

NS: What about the Purification Clubs?

SC: Those are ceramic pieces. I wanted to make objects that resembled archeological finds and also looked like body parts or weapons or tools. I was watching a lot of Cronenberg and was getting interested in the idea of body horror.

NS: They also have a totemic feel, like a trophy. Something heroic.

SC: Almost like Predator. That may have seeped in from there. In Predator II, they show the artifacts that the Predator had been collecting… you get to know more about the Predator’s taste. [laughter] I don’t remember much about that movie, but I do remember the scene when Danny Glover goes into a spaceship and finds all these artifacts, bones, and skulls. Also in eXistenZ, there’s a scene where they’re eating some kind of mutated animal and Jude Law’s character has this natural instinct to eat it, then construct a gun from the bones.

NS: Manson, gun clubs, actual clubs, glass-breaking rituals, ritualized violence is obviously important to you. Are you more interested in violent loners? Groups that end in physical or psychological violence?

SC: I’m not so interested in loners or cult leaders. More the members and/or followers in these groups and how they can be influenced. In a lot of cases these people are educated and come from good families but somehow get lost along their way and end up getting brainwashed. This happens every day in so many ways. Propaganda is a big part of it. And the people you keep company with. Also, living in New Orleans, it’s a violent city. I’m interested in how violence is used as a tool for control.

Stephen Collier (in collaboration with Brett LaBauve), Concealment Wall, 2012. Mixed media installation at the Contemporary Arts Center, New Orleans. Courtesy the artists.

NS: Concealment Wall in the "Spaces" exhibition at the Contemporary Arts Center last year felt like a culmination of all this.

SC: Yeah, it was a transparent wall with objects stuffed into it. I collaborated with Brett LaBauve on that piece. I had been researching how people have been finding all these objects in walls lately, especially in old American buildings. It’s a very old custom to put some type of sacrifice in the foundations of homes; eventually, the objects were meant to symbolize the body. So they’ve been finding a lot of shoes and clothing in the frames of houses. Mummified cats as well. It’s all to ward off evil spirits. So that’s where that piece came from, the idea of what might be in the wall that you can’t see.

NS: What was in your wall?

SC: I mummified a stuffed plush cat. There was a pile of shoes, a bottle of piss, cigarette butts, liquor bottles, text, pantyhose, a ski mask, a crumpled poster, markings, oils, and other found objects. I’ve been talking to carpenters lately and they’ve been telling me the things they find inside houses: little notes people leave for the next carpenter. I just remodeled my bathroom and found a hand-painted list of liquors on a piece of wood. I’m not sure if it’s a grocery list, a reminder, or a recipe. It’s very strange. Anyhow, there was some of that playfulness as well in the piece. I like to bring in the viewer with some sensationalism, too. Lindsay Lohan had been in the news a lot lately, so I had a cutout silhouette of her, and also a fingernail. She had “FUCK U” painted on a fingernail for one of her court dates.

NS: You talk about it so mischievously, but the piece had a real aura.

SC: There was definitely a mystical and psychological element to the piece. Most of the objects were pretty common things you see every day, but viewing them in the context of a wall changed their meaning.

NS: I came to your studio about a month ago and you had just scavenged a sign for a lost pet made with vinyl letters stuck pretty haphazardly on a cheap plastic backing with a big tire print on it.

SC: I’m still trying to figure out what I’m doing with it. [Collier shows Stillman a silkscreen made from the original lost pet sign.] Originally I was going to remake it in wood, but I think it would have taken some of the authenticity out of it. So I photographed it and printed it on the same material. The tire track is printed using a found tire and paint. It’s sort of a pathetic artifact I found on the side of the road. It sat out for a while and was run over and I kept thinking about it, so a week and a half later I went back and it was still there. I think it relates to the rest of my work somehow; the idea of the lost pet… it was probably this person’s light, and here’s this final effort. I’m sure the pet doesn’t know it’s lost! If it does, it’s probably not as sad as the owners are. You know what I found yesterday? A lost stroller sign. It was in a plastic bag and I guess some rain got on it and the colors were running. It was like it had been crying.

NS: Like with the Manson piece, you’re remaking something. Is there some attempt to capture some of the energy of the original event?

SC: The goal is for the new object to have energy of the original, but I also want to add a different aspect to it, capture the emotion. Now there is replica for almost everything…. guns, figures, newspapers, clothing, cars. People collect these things to feel closer to the experience. So I’m trying to do that with the things I’m replicating. The Manson door—the one I made—has a pink gradient, so there’s this attraction. It might not attract you mentally, but your eye will be attracted right away because of the color.

NS: So do you use color as a lure?

SC: You want to bring the viewer in, and that’s an easy way. Whether they stay depends on them and how much they want to invest in the work. But I want them to have an attraction first off.

NS: You told me recently that you were thinking about making a whole show around the theme of lost pets. What are some other hypotheticals you’re kicking around?

SC: There’s one piece I’ve been thinking about for a while, but I’d need a large group and a space. It’s a paintball field and I want to have the objects you maneuver around be objects from art history: remakes of Donald Judds, Warhols, Rothkos, Chamberlains, and the list can go on. So you’re maneuvering around art history while firing upon your opponent. They’d probably be very pathetic replicas. That was one of the things I wanted to do at the CAC for "Spaces."

Stephen Collier, both Untitled, 2013. Both oil, acrylic, enamel, xerox, sheetrock, and plywood. Courtesy the artist.

NS: Obviously you’ve got this affinity for the pathetic. We talked before we turned the recorder on about our shared love of Paul Thek and Mike Kelley, for a lot of reasons, but especially their eye for debased American stuff. But you’re dealing with power issues in a completely sincere way. Could you discuss these new pieces and how they relate to the pathetic and also to power?

SC: This is a new series using structures or constructions that play with the idea of walls being a physical as well as psychological divider. They are made of sheetrock wallpapered with a brick wall print and plywood backing. The brick wall image was taken from an inlay from another situational target. It was just a small section of wall I scanned and expanded. Automatically, it reminded me of a firing squad and the relationship between those firing and those being fired at. I thought it would make an interesting surface for portraits.

The sheetrock is cut, exposing a material underneath. On the outer surface—the brick wallpaper—I painted gestures based on facial make-up and masks you see on Mardi Gras Day. Some of it resembles Native American war paint. I am playing with the idea of interiors and exteriors and how people behave differently when they’re in disguise or playing a role. There’s a feeling of empowerment, protection, and freedom. This could be a good thing or a bad thing depending on the situation and the individual. Also, the structures are sort of precise and controlled, almost in a Minimalist tradition, and the paint treatment on the surface is loose and a little garish—not at all Minimalist.

Editor's Note

Nick Stillman interviewed Stephen Collier on the occasion of the artist's exhibition on view April 13 through May 4, 2013 at the Acadiana Center for the Arts (101 West Vermilion Street) in Lafayette.