Depths of Field: The Portraiture of Jonathan Traviesa

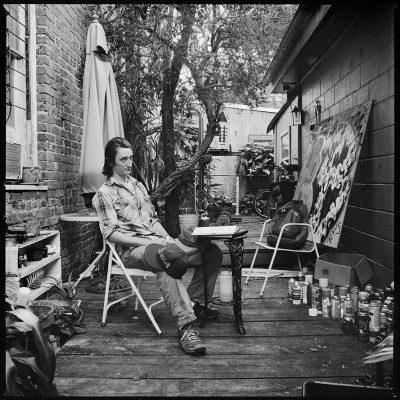

Jonathan Traviesa, Felix, 2010. Pigment print. Courtesy the artist.

"...I planned it, I sawed it, / I nailed it, and I / will live in it until it kills me." – Alan Dugan, “Love Song: I and Thou”

Most of his subjects are smiling, though only slightly. They seem bemused more than anything else, wondering why he makes so much of their presence. Sometimes they pose with their pets, other times with their cars, but most often they pose with their front doors: closed, open, or ajar. Their gazes—square into the lens, or askance, at the barest of angles—seem to say Yes. I live here. And?

This defiant attitude characterizes an ongoing portraiture project by Jonathan Traviesa, a photographer based in the Bywater neighborhood of New Orleans. Traviesa moved to Louisiana in the 1990s, having first studied photography in his native Florida. Knowing no one before his arrival, he enrolled in classes at the New Orleans Academy of Fine Arts, where the seeds for his project were first planted. The work began slowly: he started photographing his friends and acquaintances first, then their friends and their acquaintances, then the occasional stranger; and, as years passed, he saw he had built a coherent body of work.

Traviesa’s work was first collected in the book Portraits: Photographs in New Orleans, 1998-2009, a volume of 100 photographs published by UNO Press. A 2009 grant from the New Orleans Photo Alliance enabled him to undertake 70 more over the past year, 15 of which appear in a recent issue of the online publication One, One Thousand. In many ways, these new images build on the strengths of the overall project. Investigating the central relationship between an individual and his or her home, Traviesa’s work raises compelling visual questions about identity, rootedness, and sense of place.

Jonathan Traviesa, Allison, 2010. Pigment print. Courtesy the artist.

Traviesa has claimed that his interest in New Orleans comes primarily from “the effect that it has on people’s personalities”—the way, he argues, that the city directly affects its residents. “It doesn’t take long for you to be here to feel something,” he says. Even though the entirety of his portraiture is based in New Orleans, he avoids reading too deeply into its idiosyncrasies: in particular, the relationship between houses and people. Many of the houses he shoots bear no defining local markers, removing the potential obstructions of iconography or caricature, and rendering the argument of his work even more cogent: that New Orleans, particularly post-Katrina New Orleans, enjoys a right to existence as much as any other city whose balconies may not be garlanded with beads.

Those images that do depict beads, however, render them in exquisite detail, evidence of Traviesa’s skill in arranging complex textures and forms. In one image of a woman and her dog in a garden, the pattern on her dress threatens to fade into the foliage, leaving only the solid tones of skin behind. This playful juxtaposition converses freely with a second image of another woman in a garden, this one wearing a snow-white ball gown, radiant among the surrounding leaves; the two together beckon a third, of a woman in a dark turtleneck standing before a lightly scoured brick wall. Each image invites the eye to graze across its rich surfaces rewarding the viewer with a deeper understanding of contrasts—internally, within a single image, and externally, across his body of work.

On this basis, Traviesa is more than a documentarian, a label he does not, on asking, refuse. It is more accurate to label him an interpreter, one who understands the central interplay between individual and home as one of continual negotiation. He engages this interplay by relating elements in space, rendering the middle distance between his subjects into an active zone for the fertilization of narratives: buckets uncapped and hoses uncoiled, as though he had interrupted a Saturday afternoon outside, or books and binders on a wicker couch, evidence of a different kind of work. In many of his images, signs of some aspect of construction or improvement are evident: furniture and appliances await collection, or a clutch of exposed wiring suggests a renovation project underway.

Jonathan Traviesa, Bud, 2010. Pigment print. Courtesy the artist.

If his individual images address the role a human plays within the drama of a house, his portraiture overall addresses the role a house plays within the drama of a city, namely, a city that is still battling back from its recent near-death. Traviesa claims that his work only tangentially addresses Hurricane Katrina, arguing only that “Katrina will always have some index to the totality of the project, some inherent relationship to it.” Yet the shadow of the storm looms larger within the work than he suggests, as these photographs impel viewers to reconsider their own fragile relationship to their homes. At the same time, they explore the narratives of homes in different neighborhoods across the city, including homes rebuilt by communities of immigrant laborers from Central and South America—communities which Elizabeth Fussell, a researcher at Washington State University, notes nearly doubled in size during the year after the storm. Recognizing the underappreciated role that they have played—the aspect of that Katrina "index" that lends his work its subtle political edge—Traviesa has included a number of these men and women in the project. “The story of these newer residents has been fundamental to rebuilding the city,” he argues. “What is important from my perspective is to put their stories on the same platform as any other: not just at the job site, but at their own homes.”

The technical use of his instrument keeps this edge sharp. Traviesa’s use of depth of field in particular is astonishingly varied, and becomes the location of his greatest opportunities. As noted, the majority of the photographs situate a number of elements in relation to one another: the house within the street, the street within the neighborhood, the resident within his or her profession (in one, a graffiti artist poses before his cans of spray paint, his backpack, and a canvas on which the design echoes the tree limb facing it, a compositional pas de deux). At their finest, his photographs propose a recession of space that invites the viewer to reimagine depth of field as a set of layered depths of field, depths through which one comes to understand the nature of these homes depicted precisely by traveling imaginatively through them. To arrive back at home, having traveled the curvature of the earth; to arrive, as T. S. Eliot wrote in Four Quartets, “where we started / And know the place for the first time.”

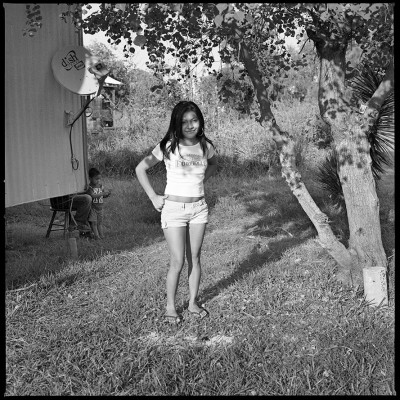

To know that place is, first and foremost, an opportunity: to call a place home is to make a place home. Home, as depicted by Traviesa, becomes a place not just of living but of dwelling, of communing and of welcoming, of ensuring that front door, iconic for a different reason, is always open. What a home asks of us in return for the gifts it offers is more than just its upkeep and repair. It requires a continual renewal of affection and of care, a glad population of friends and family and community. Amid all the lyric gestures buried within Traviesa's work, one subtle moment stands out: in the photograph of a woman standing in her backyard, the grasses receding behind her, another structure barely visible at their edge, the corner of the house casting a deep shadow over two more people. One is a man, the other a child of no more than four or five. The house obscures them both, but only just, revealing the depth of the familial bond: this is their home, they have made it and will keep it, and no one, not even a storm, can take it away.

Jonathan Traviesa, Sarita, 2010. Pigment print. Courtesy the artist.