State of Affairs: Anne Gisleson

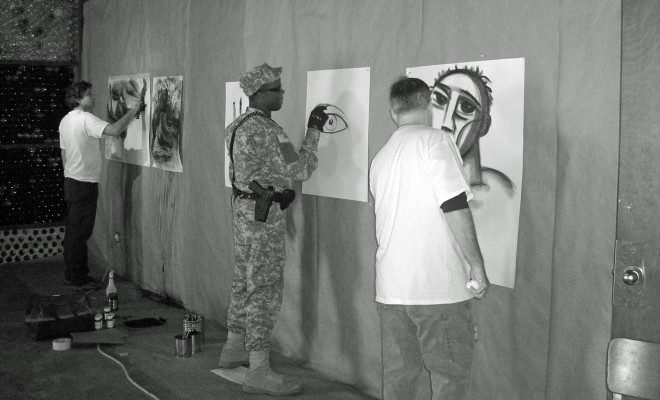

An armed member of the National Guard draws alongside other participants at the first Draw-a-thon event in 2006.

Editor's Note

For the second interview in the series “State of Affairs,” which examines the current role of the visual arts in New Orleans, Pelican Bomb editor Cameron Shaw talks with Anne Gisleson. A writer and educator, Gisleson teaches at the New Orleans Center for Creative Arts. She is the co-founder of Press Street, a local non-profit that focuses on the relationship between text and image. Press Street promotes art and literature in the community through events and publications, as well as through exhibitions at its artist-run gallery space, Antenna.

Cameron Shaw: This year marks the fifth anniversary of Press Street. How did the organization come about?

Anne Gisleson: We actually started Intersection | New Orleans, our first book project, in the summer of 2005. We had the idea to pair 25 artists with 25 writers—who were based in New Orleans or who had recently lived in the city—to do blind collaborations about 25 street intersections in the city. We were just beginning to get submissions when the storm hit. We assumed the project was finished because so many people had left the city and some weren’t coming back. At first, asking people who had been flooded out to think about a book was hard to fathom, but then we began to see we needed the book more than ever. It became greater than just the intersection of art and writing or the idea of street intersections; it was a way of thinking about life before and after Katrina. For some of the planned pairings, the piece of writing came in before the storm and the piece of artwork after—or some other combination—making the idea of intersection more complex.

Since right after the storm, we’d been doing readings at businesses that hadn’t yet reopened—Saturn Bar, Preservation Hall—to draw attention to the fact that there was still vitality in the city. When the book finally came out that next summer, in 2006, we had a show of the art that was included at L’art Noir, a space being renovated by Jeffery Holmes and Andrea Garland. They had been doing installations on the neutral ground for months, but this was considered the first indoor St. Claude art show. The space had been flooded and was completely gutted, so we hung contractor paper on the walls. Hundreds of people showed up from all over town. It was clear how hungry people were for events.

CS: How would you say the organization has changed in its focus over the last five years?

AG: In the beginning the group had no fixed physical location, so we would gather at my house—my husband Brad Benischek, writers Ken Foster and Case Miller, and my sister Susan Gisleson, with others coming and going. Everything happened around a kitchen table, which is one of the reasons we wanted to have a table in Antenna for the anniversary show in March. It always got people talking and generated a dynamic exchange of ideas. After Katrina, there were a lot of brownouts in the neighborhood. The power would go out and we would keep talking. It was a very fertile and open atmosphere at that time. Even though there was a lot of stress, we could still get around a kitchen table and talk about what was going on and throw out ideas and then actually do some of them. There was a real sense of accomplishment.

In 2008, Courtney Egan and Shawn Hall approached us about opening a gallery. By then the St. Claude arts scene was just starting up, and that choice to create Antenna has changed us a lot as an organization—made us more focused on visual arts exhibitions, on maintaining the space. It’s also attracted a whole new crop of visual artists to our collective, some locally established, some newcomers to the city: Natalie McLaurin, Jerald White, James Goedert, Angela Driscoll, Robin Levy, Laura Gipson, Robin Wallis Atkinson, and Bob Snead. Writer Nathan Martin has recently started a literary blog under Press Street called Room 220, and we hope to have more readings and salons at the gallery. And, of course, we continue to work on our collaborative book projects and Draw-a-thon.

CS: Draw-a-thon was one of those initial kitchen-table ideas. What were your expectations for that event?

AG: We had no idea, absolutely no idea what to expect. We just wanted to get people together and start drawing.

CS: As an outlet?

AG: As a lot of things…there were many philosophical underpinnings to that first Draw-a-thon in 2006, like how drawing helps you connect to the world around you. We thought about the line and connecting and seeing and the physical act of doing it—a way to connect to other people and to help you connect to things happening. That theme of connection is at the heart of everything we do as an organization.

It started off as Brad’s fun idea to have a 24-hour marathon of continuous activity with free drawing workshops. We covered the walls of an old warehouse by the railroad tracks with paper, so people could write on them. We didn’t know if it was going to be 25 or 250 people, and the first people who showed up were the National Guard. It was around 6 am, and I don’t know what they came for initially but within minutes they were drawing.

CS: That’s an important image.

AG: It is, because at the time the city still felt embattled. We still had Humvees driving around our neighborhood downtown. When these guys came in with their guns and started drawing, we knew we were onto something. Then families came and, in the middle of the night, you get all kinds of people coming! One of the reasons we consider it our most important event—the most successful thing that we do in terms of community building—is because it brings people in from all over. I think art has the capacity to facilitate dialogue if it’s done right—if it’s done thoughtfully.

CS: What are the concerns that go into something being done right?

AG: We didn’t go into Draw-a-thon with a set ideology. We weren’t thinking about race or class or gender.

CS: That’s an interesting distinction that you’re making between a philosophical mission and an ideological one. To dictate how an event should exist in terms of race or gender inherently privileges a biased perspective—your own understanding of those terms. When you take that out of the equation, it makes more room for other people’s understandings and their own experiences.

AG: Absolutely. I’ve seen so many events fail because of this top-down ideology. Similarly, you can’t just throw in contrived elements of a specific community’s culture and expect it to produce real and meaningful interactions among people.

CS: I’m reminded of the essay you wrote for Waiting for Godot in New Orleans: A Field Guide, which Paul Chan edited. In response to the “gumbo party” and second line staged for Chan’s play, you talked about the danger of self-parody and provincialism, of always pointing to, what you called, “the same uniquenessess.” What do you think artists can do to call attention to New Orleans’ special attributes without it devolving into parody or empty spectacle, especially now that so many young artists are being drawn to the city?

AG: It’s such a fine line. I’ve felt sometimes that I was too harsh in that essay, but I think there is a penchant to exoticize and aestheticize New Orleans, which can undermine the real complexity and dimension of the place. It’s easy to augment your own work with New Orleans’ cultural elements to suddenly make it seem more interesting, especially to those outside the city. Real second lines are amazing and powerful, so people are understandably drawn to these things, especially if they’re coming from places with less cultural depth. The question of what artists just arriving can do? I can say what not to do: don’t just use New Orleans culture as grant fodder. Try to figure out what real community engagement means or why these aspects of the city’s cultural landscape are important to your work. Examine what your own motives are first. That is the first step.

CS: Can you talk about the genesis of How to Rebuild a City?

AG: It’s a little book, but it took a lot of time! I was at Bacchanal with my husband and my sisters and brother-in-law, and I was complaining about an anthology that was coming out. We were three years beyond Katrina at this point, and an essay had been chosen on the looting of the Robért grocery store, which to this day has not reopened. We still don’t have a real grocery store in this neighborhood! I was so sensitive about how New Orleans was being portrayed because our national image has a profound impact on people’s support of the rebuilding. Having something out there that I thought callously romanticized the immediate aftermath and destruction, when there were actually so many incredible rebuilding stories at that time, was upsetting. We decided the next book project would be about the good work being done down here. Over a hundred people and organizations contributed to this little book alone—rebuilding a city is the ultimate collaborative project.

CS: Beginning as a rebuilding organization, Press Street is a part of that “collaborative project,” as you say. How do you continue to keep it relevant as the needs of the city change?

AG: When we began, it felt like the organization was necessary to get things moving and restarted, but now we’ve taken on more of a support role. I think that’s something Press Street does well—support other artists, other initiatives, and other organizations. There’s no shelf life for that. Artists always need support.