30 Americans in New Orleans: Gia Hamilton with Apsu, Isael, and Kush Amen

Nick Cave, Soundsuits, both 2008. Synthetic hair, fiberglass, and metal (left). Fabric, sequins, fiberglass, and metal (right). Courtesy the artist and the Rubell Family Collection, Miami.

Editor's Note

The next set of responses in our series "30 Americans in New Orleans" features Gia Hamilton and sons Apsu, Isael, and Kush Amen. Offering an intergenerational take, the Hamiltons used the "30 Americans" exhibition as an opportunity to reflect on family, traditions, and creativity.

Gia Hamilton: True to form, I arrived at the Contemporary Arts Center with my four little boys to see "30 Americans" on a Sunday afternoon. I was almost embarrassed that I had talked the show up to them as much as I did, all the while knowing that a twelve, nine, six, and one year-old would not share the same enthusiasm. But they humored me and agreed to share their thoughts, feelings, and gut reactions to the work.

As toddlers, my two oldest sons, Kush Amen and Apsu, sat in their baby carriers alongside silent spectators for Jean-Michel Basquiat's show at the Brooklyn Museum in 2005. And this past winter, Gordon Parks' "The Making of an Argument" exhibition at the New Orleans Museum of Art sparked Kush's passion for photography. My four boys are no strangers to the museum. While I regularly drag them to see art or invite them to participate in the art making process, "30 Americans" was particularly significant to me. That day it served as a touchstone for so many stories about their own family history and the invention of their future. In the galleries, I recalled my father making a connection between Nick Cave’s Soundsuits and local Mardi Gras Indian and second line traditions. He often talked about the African diaspora and the links between performance and visual culture. I remembered following the second line when I was young and learning the proper place for onlookers. As I reenacted the scene of me as a little girl clapping and dancing on St. Joseph's night, I asked the boys if they could imagine wearing Cave's works of art and, if so, what kind of "character" they would become. This conjured up many images for Isael, my six year-old self-proclaimed artist. He immediately reminded me of the superhero family we had invented called the Power Rock Family.

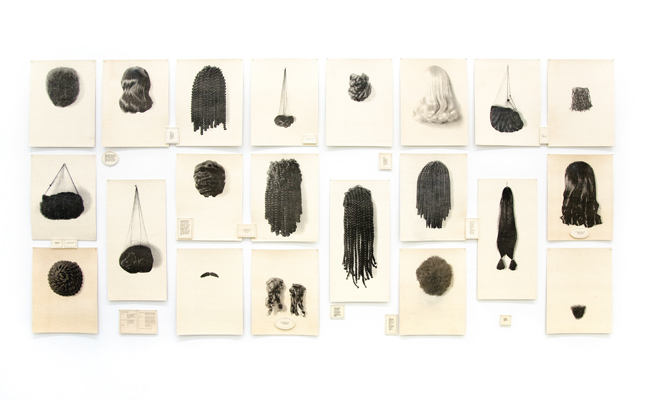

The Rubell Family Collection represented a chronology of black history and experiences that I shared, as a native New Orleanian and late '90s bohemian transplant in Brooklyn, and that I felt were essential to share with my young black boys growing up in America today. Lorna Simpson's Wigs (Portfolio), 1994, created dialogue about hair and female beauty, prominent themes of good and bad hair in New Orleans, and allowed me to further explain why I choose to wear my hair in its natural state. In this city, where "post-Katrina" is still as relevant a term as its newer counterpart "post-racial," "30 Americans" prompted me to think about the truth in the latter. Could my sons in fact sustain and thrive outside of the constructs of race, class, or gender and go on to create a new identity, one that would be self-imposed? Perhaps sharing this experience in the galleries would prompt them to ask more questions about identity and their role in shaping their own. At the very least, I knew that the visual stimuli would make a lasting imprint. Sharing this show with my family reminded me that there is no box, no ceiling, only the ones that we create.

Lorna Simpson, Wigs (Portfolio), 1994. Portfolio of 21 lithographs on felt with 17 lithographed felt text panels. Courtesy the artist and the Rubell Family Collection, Miami.

Instantly drawn to Kara Walker's Camptown Ladies, 1998, Isael, age six, proceeded to sit down on the floor and begin drawing, unprompted.

Isael: I make books and draw pictures, sometimes I make abstract work, you don’t know what it is…but I do. I want to draw on the walls and tell a story.

At nine, Kush Amen, a budding photographer, agreed to take the family photos for the day and capture the experience. Kush had a visceral response and attraction to Kehinde Wiley's Equestrian Portrait of the Count Duke Olivares, 2005.

Kush Amen: In my mind it says that African-American people are important. He has a sword, a horse. When people look at him, he is respected and he deserves what he has.

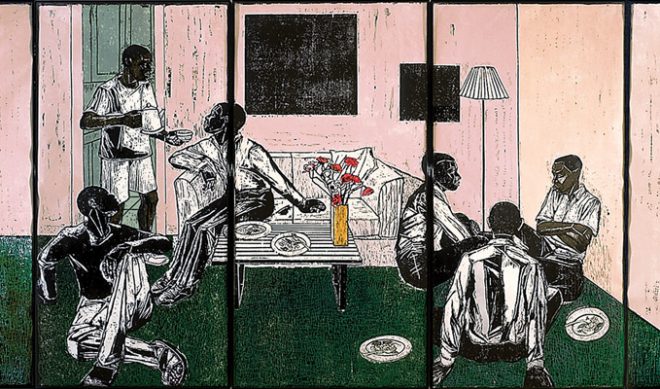

And at almost 13, Apsu surprisingly picked Kerry James Marshall's 12-panel woodcut as his favorite work.

Apsu: The design tells a story. Everyone is making conversation, having a good time. It reminds me of living in Brooklyn in our apartment and having people over.

Kerry James Marshall, Untitled, 1998-1999 (detail). Twelve panels, eight-color unique woodcut. Courtesy the artist and the Rubell Family Collection, Miami.

Editor's Note

Born and raised in New Orleans, Gia Hamilton is the Director of the Joan Mitchell Center. She is the mother of four boys—Kush Amen, Isael, Apsu, and Rhythm Amir.

"30 Americans" on view through June 15 at the Contemporary Arts Center (900 Camp Street) in New Orleans.