Seeing Is Believing: ISeeChange’s Vision for Environmentalism

Brooke Sauvage reflects on ISeeChange, an initiative that uses the Internet to connect personal observations with larger investigations into the effects of climate change.

At an event last year on St. Bernard Avenue, Julia Kumari Drapkin and Lindsey Wagner created an outdoor display that used different colored ropes to represent water heights at various flood events. The presentation also included photographs alongside audio recordings of personal reflections on flooding in the area. Photo by Sabree Hill.

We live in a time of dire forecasts.

News headlines avowing imminent environmental catastrophe float around like wayward icebergs. Carbon emissions are on the rise, as are sea levels. We lurch into another hurricane season with last year’s devastation in Texas, Florida, and Puerto Rico still in mind. California continues to grapple with fires, and in New Orleans, the ongoing conversation sparked by failed pumps during last year’s flooding highlights both institutional incompetency and infrastructure failure. And yet, in spite of the urgency of these catastrophes all over the world, we face collective paralysis in determining how to reform our relationship to consumption, to weather, to water.

A group of journalists, researchers, designers, software developers, and artists led by Julia Kumari Drapkin and Lindsey Wagner, created the online portal ISeeChange to engage citizens in observing weather events. Kumari Drapkin, who lives in New Orleans, and Wagner, who lives in Boston, were residents at A Studio in the Woods last year where they explored creative placemaking as it related to flooding in the Gentilly neighborhood.

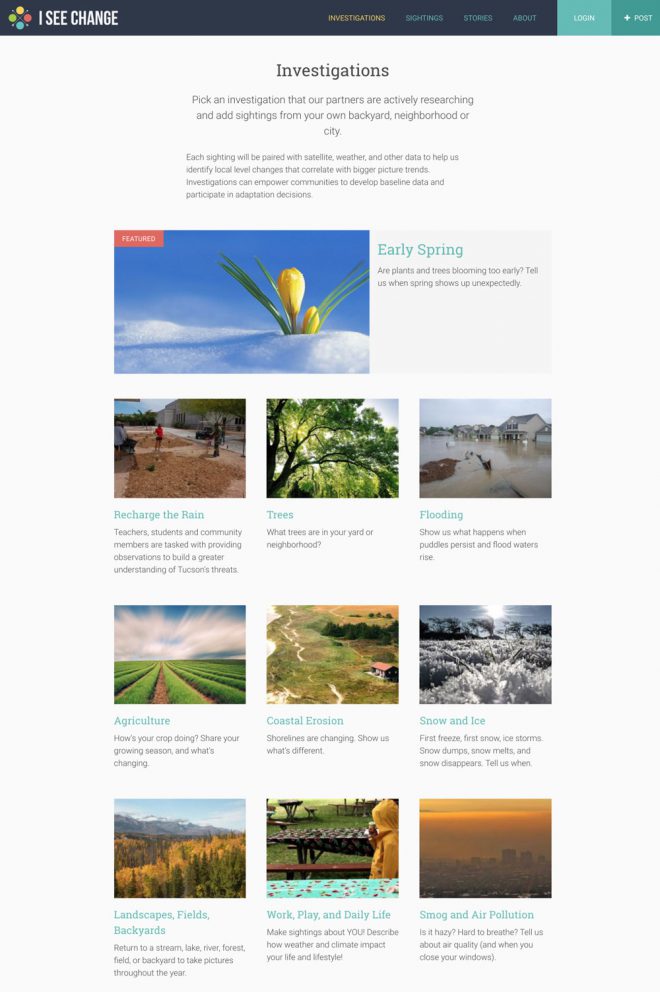

Online, ISeeChange comprises a three-step pathway. The ISeeChange team identifies dozens of topics, named “investigations,” affecting people all over the world, among them high tides and sea-level rise, extreme weather events, and coastal erosion. Users upload written accounts and photos as “sightings” that are then tacked to investigations. Data collected through the investigations are then compiled into stories. ISeeChange hopes that these citizen observations can inform reporting, policy reform, and data collection in a more precise, granular way than traditional methods have.

But what’s distinct in this process from how we traditionally process climate change? ISeeChange asks all users—all citizens, all humans—to be conscious creators. The nature of data collection becomes more narrative and relatable. The earth’s broad ecological shifts, rarely understood within the myopic scope of one human lifetime, are rendered in personal terms. For instance, one user who experienced a heat wave in Harlem posted that her three-month-old grandson enjoyed taking showers and being by the fan.

Ordinarily, scientists record a heat wave by measuring outside temperatures. However, in urban centers, extreme heat can be linked to interior spaces, as buildings and pavement have been found to trap heat. Observations like the one above help distinguish, through storytelling, between indoor and outdoor temperatures in Harlem, and allow users to share their personal strategies for safeguarding against extreme weather.

ISeeChange’s website groups personal, local observations (“sightings”) into topics (“investigations”) of international concern.

New Orleans native Kumari Drapkin experienced last year’s August 5 flood event from her kayak. She received warning of the flood risk from ISeeChange 45 minutes before the National Weather Service, in fact, and noticed on her own property in Gentilly that the rain seemed to be unusually intense. Upon venturing out, she came across an elderly woman on foot, stranded after making a run to get food from the corner store. Kumari Drapkin waited with her until the fire department showed up. The woman, who had recently had surgery, had been stuck in the water for four hours. She didn’t trust anyone who tried to help her. Finally, the fire department asked Kumari Drapkin for her help.

“They actually commandeered my kayak to rescue her,” she said. Kumari Drapkin learned that most of the calls to 911 come from those the fire department cheekily refers to as “frequent flyers,” those who use emergency services with some regularity, often elderly people with mobility issues or health problems, most of whom live alone. “We need to create better networks to check on the people who need us in their neighborhoods,” she said. “We really want ISeeChange to be a service, to be practical to community members.”

Much of what ISeeChange has known about ongoing flooding issues in New Orleans’ St. Bernard corridor came from user Destiney Bell. She noticed that her yard, on the corner on Harrison and St. Bernard Avenues flooded after almost every rainstorm. The water drummed up all manner of debris, and cars driving through the so-called “Lake Harrison” sent wakes ricocheting into the yard.

So Bell got involved. She began by talking to her neighbors. Soon thereafter she was taking timestamped photos and measuring rainfall from her porch with a rain gauge. Her findings were fairly outstanding: That a half-hour of heavy rain was enough to flood her yard with a foot of water. ISeeChange had succeeded in inspiring a nanny by trade to become a citizen scientist. “Data on a graph is not particularly inviting or compelling [to communities],” Kumari Drapkin told me. “It doesn’t necessarily engender the kind of participation that we want.”

During their residency at A Studio in the Woods, Kumari Drapkin and Wagner painted on sidewalks to show the extent of flooding in hotspots around New Orleans. They created elevation lines with string to show sea level. They organized a block party in Gentilly, with food, music, and bounce castles, and talked about the history of the neighborhood. They partnered with Bring Your Own to create a storytelling event centered around the August flooding that brought together members of the Sewerage and Water Board of New Orleans as well as people whose properties flooded.

ISeeChange works with communities. They induce average people to engage with their environments every day: Because it’s not safe for their children to play outside during a rainstorm. Because they worry about whether their elderly neighbors down the street will be okay during the next hurricane. Because they care about their loved ones more than they care about maps, charts, and figures. “When we’re at our best we should be at that level of call and response,” Kumari Drapkin said. “These stories can live in harmony with this data and be much more effective.”