Mapping Queer History: An Interview with David Jack Browning, Abram Himelstein, and Aesha Rasheed

Ann Hackett talks to the creators of Queer Cartography about their mission to provide educational tools about New Orleans’ history.

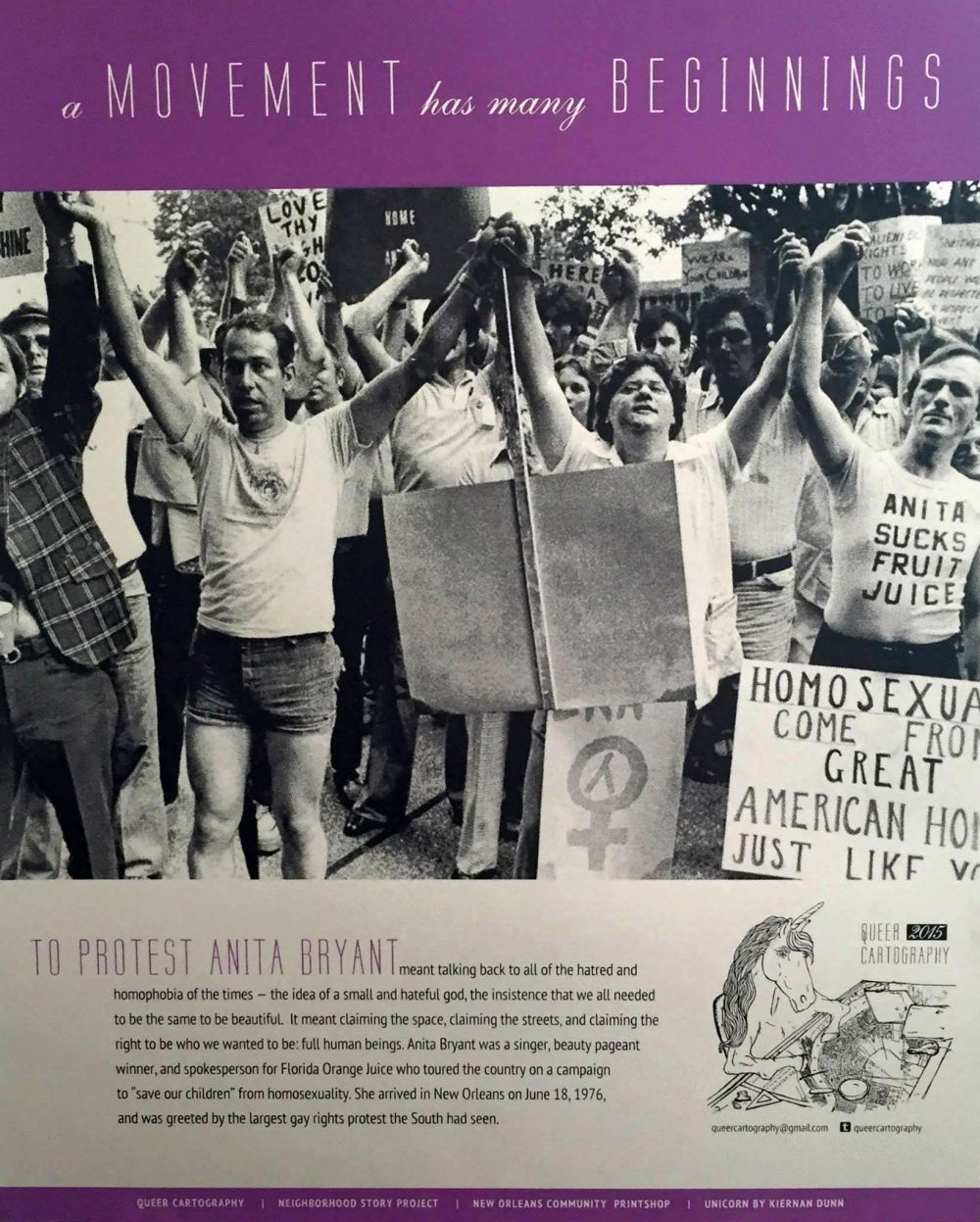

A Queer Cartography poster from 2015.

Editor's Note

Queer Cartography is a project that chronicles the LGBTQ history of New Orleans, focusing especially on stories that are not widely known. Every year since 2015, Queer Cartography has produced a series of posters, each of which illuminates a significant moment, organization, location, or person. Earlier this year, I spoke with Queer Cartography’s three organizers: Aesha Rasheed, David Jack Browning, and Abram Himelstein.

Queer Cartography is published by the Neighborhood Story Project, a non-profit that collects and publishes New Orleans stories. I’ve worked for the Neighborhood Story Project on and off since 2016.

—Ann Hackett

Ann Hackett: What is Queer Cartography?

Aesha Rasheed: Queer Cartography is a poster series that honors New Orleans LGBTQ elders and ancestors, centering on black and brown people, femme people, trans people, and folks whose histories are untold.

Ann Hackett: How did you start collaborating?

David Jack Browning: After the 40th anniversary of the Upstairs Lounge fire, Aesha and I, both transplants [to New Orleans], were sitting on the porch with a glass of wine. During the 30th anniversary, there was seemingly no mention of it, but when the 40th anniversary came [in 2013], there were plays, every news outlet had a take, and there was a ton of coverage. It was this moment of realizing it took 40 years for us to talk publicly about something so horrific that people knew about in the city’s history. So, if it took 40 years for us to talk about something people remembered, what are the other stories that have had no coverage?

Aesha Rasheed: I organize with Southerners on New Ground. Much of our work is lifting up and building on the legacy of Southern liberation work. We spend a lot of time thinking about who came before. We know the stories of the folks on the margins don’t get told, and much of our work is unearthing stories and telling them to each other, reminding each other that we exist and that these fights for liberation have been ongoing. People have been pushing back against heteropatriarchy and against white supremacy and against forces of oppression for a long, long time. Knowing that informed my desire to learn for myself and to have representations out there for those who come behind us.

I didn’t see representations of who I am growing up. I didn’t see black lesbians in media, on walls, in books, anywhere in the world. I didn’t see queer Muslims. I didn’t see myself. I had to imagine myself into existence. There’s a lot of loss for me in those years. We can offer the generation behind us their own stories and reflections of themselves: Posters, because I want the stories to be accessible, not locked away in books, archives, or in the heads of those people who get curious enough to poke around—so a young queer kid or someone parenting a trans child sees these posters and has an example of who they are.

Abram Himelstein: For me it happened when I was walking with Aesha at the Endless Gaycation parade [in 2013]. It was beautiful but very ahistorical, and there was a lot of conversation about queering the city which felt untrue. I grew up in South Mississippi. New Orleans was where you went once you figured out that you might be gay. I was like, “Wait. What are you talking about? Making the city gay or making the city queer?” This city has been gay since I’ve known about it. I wanted to personally know about the gay history in the city.

Aesha Rasheed: A lot of [the history] out there was about white, gay men. There have been all kinds of gendered people, queer people, races of people, and lots of black and brown queer people surviving, working, transforming the city, and being integral in the movement work of our communities.

A Queer Cartography poster from 2015.

Ann Hackett: What goes into making a poster?

David Jack Browning: Some of the sets of posters we’ve done have had a common thread or a common timeframe. But we have to ask: Are we giving voice to the voiceless?

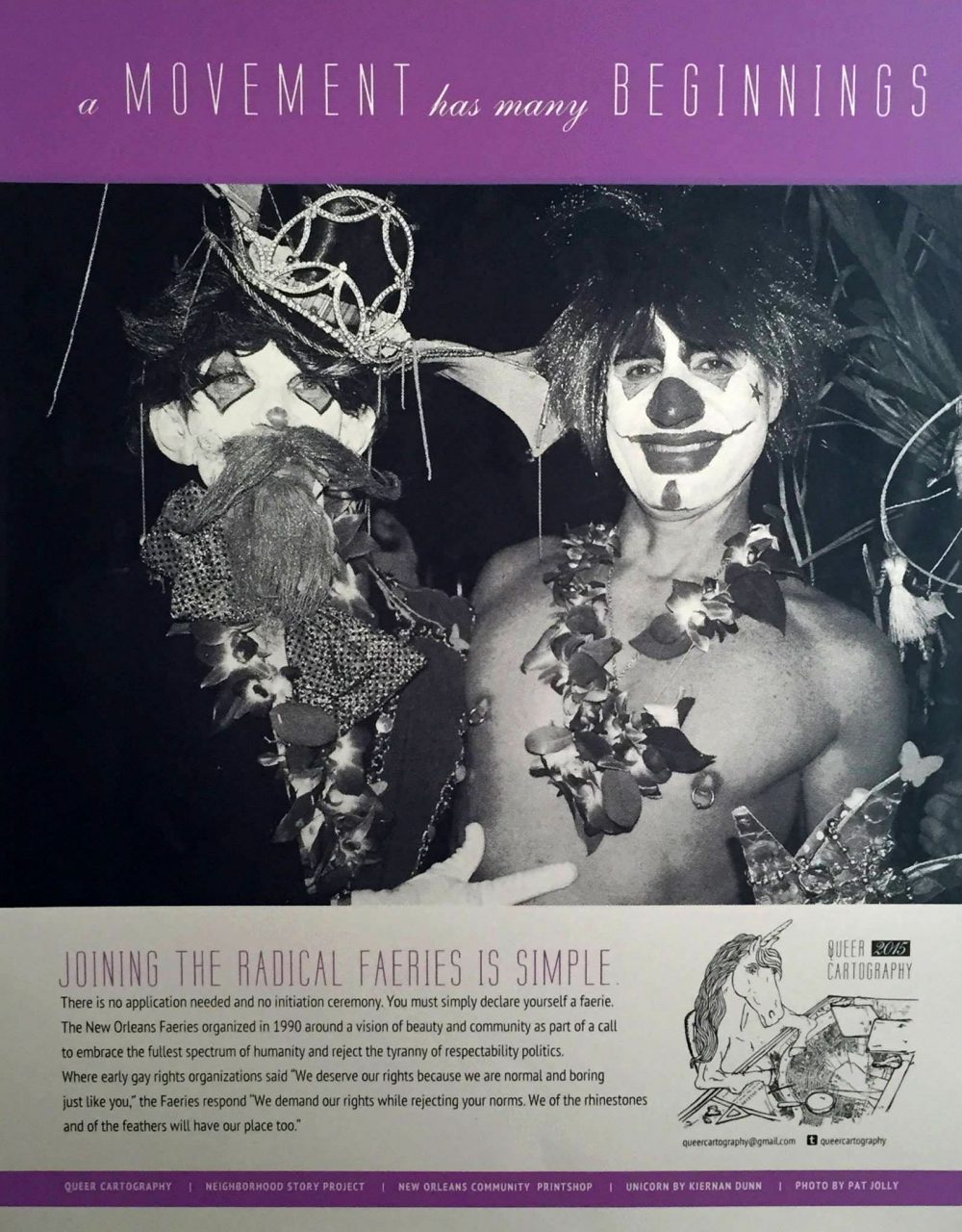

Aesha Rasheed: We do research and sometimes interviews. For the Radical Faeries poster, Jack [Browning] and I talked to folks in those communities, spent time, went to potlucks. No interviews, just talking to people. For the Fernando Rios poster, there was a lot of in-person research. Jack dug some information out of the Times-Picayune archives. The original news story was horrifically offensive. They blamed the victim [Rios] and denied that a crime occured. We got to reframe that story to honor the person whose life was taken.

David Jack Browning: Giving Rios some justice. That was the point of that one. These privileged, white Tulane students beat this guy to death and put their entire defense on his character.

Abram Himelstein: And the shape of his head.

David Jack Browning: And the shape of his head! It also speaks to the bullshit forensics in that case. It’s depressing, but in the end, I love that poster because we have a connection to Fernando Rios that the city brushed aside.

Aesha Rasheed: Jack does the design. We all do a lot of writing. I love that Abram calls it a love letter. We don’t try to be cold and calculated. We try to tell a story that’s full of humanity.

Ann Hackett: Do you have any examples that surprised you?

David Jack Browning: The poster about how clothing laws were changed. Eloy [Hinojosa, a popular drag performer on Bourbon Street in the 1970s,] was the plaintiff against the state who got those laws changed.

Abram Himelstein: Eloy[’s case] tells this amazing story of being in the paddy wagon, and the police are doing a perp walk, trying to humiliate all the drag queens. The cops have brought their families for a giggle. They pull up a block from the station to make them walk extra. They hold them in the paddy wagon so that a crowd can assemble. And Eloy really gives them a show, walking out of the paddy wagon like, Here I am. I am alive. I am beautiful. You’re trying to laugh at me, but I have no shame.

Aesha Rasheed: The poster [for singer and performer Patsy Vidalia, who performed at the Dew Drop Inn in the 1940s] talks about black spaces navigating gender in a complex way. There’s been a lot of work [by society] over the years to teach me and everyone I know that black people are homophobic. To have this representation of a black space that was embracing, which affirms what I know to be true in my own lived experience, and also that what I, my mother, what a lot of people were told, wasn’t true, that’s a surprise and an affirmation.

Ann Hackett: It seems like there are fewer queer spaces in the city than there used to be.

Aesha Rasheed: The hopeful version is that queerness has expanded outside of designated queer spaces. We can be anywhere. We always have been everywhere, but people can say, “I’m fully present everywhere.” But I worry that we have assimilated. It’s not that we don’t need queer spaces, but that we’re told that they’re unnecessary. The belief that queer spaces were just about the sex is part of the myth. A lot of what happened, is happening, is organizing around multiplicities of oppressions and how people live at the intersection of those. When you convince people that they can assimilate out, you are leaving people behind. It’s my dark worry that certain LGBTQ people, mostly around class and race privileges, have access to more spaces. People with those privileges can go to any bar. That’s great. Meanwhile black trans women can go nowhere. Or nowhere safe from harassment or harm.

Ann Hackett: What response have you gotten from New Orleans?

Aesha Rasheed: People generally love it.

Abram Himelstein: Or don’t tell us.

David Jack Browning: The nine posters we’ve made have a lived narrative. There’s a play that’s based on a lot of the posters called The BreakOUT. If nothing else happens, it was worthwhile.

Aesha Rasheed: Loud, which is a queer youth theater project, did a production using the posters as information, as text to lift up the stories they wanted to tell in their production. They wrote acts about some of the events in the posters. Queer people, young queer people, and trans people are looking at these posters, remembering that history, talking to each other about how that history sets up the reality of their lives and what they have to continue to push against. My brother went to that show, and it shifted our conversations about gender, who makes gender, and how we define ourselves.

A Queer Cartography poster from 2015.

Ann Hackett: Your project is also about cartography.

David Jack Browning: It’s mapping through storytelling.

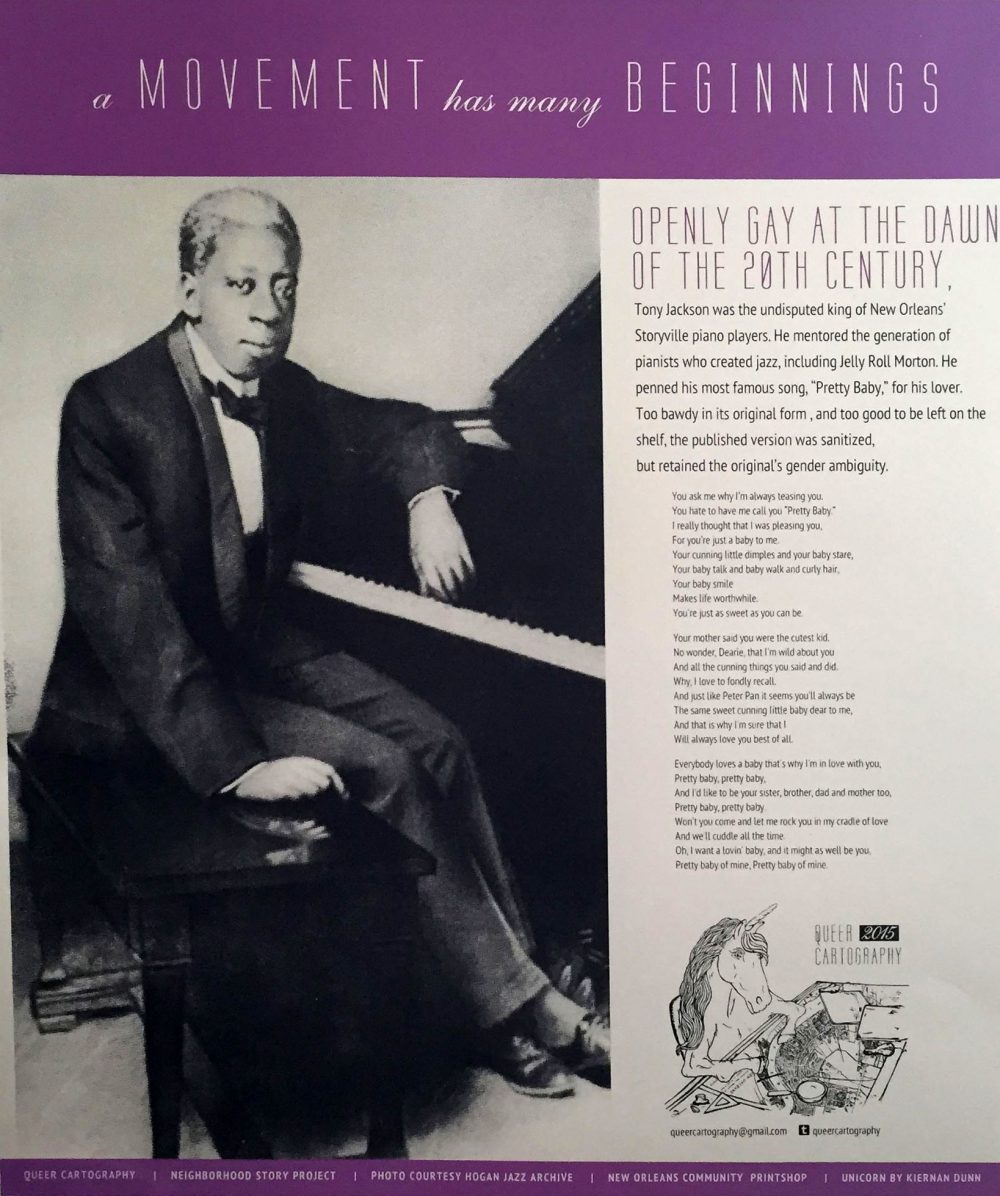

Abram Himelstein: Making a map declares importance. Living here post-Katrina after the massive demographic shift, there’s always the layer of what was here before. But having been part of this project, it’s also, Oh right, Tony Jackson was living as an out gay man 100 years ago.

David Jack Browning: I wonder, what were the gay legends told to [pianist] Tony Jackson? When we first moved here, we heard stories on the bar stool. In this 300th year [New Orleans tricentennial], who is telling and who is listening? Like Abram said, we’ve always been here. We’re always going to be here.

Ann Hackett: What’s next?

Abram Himelstein: The LGBTQ Fund of Greater New Orleans Foundation is funding putting Queer Cartography in 15 schools.

Ann Hackett: What would it have been like to see Queer Cartography in your school?

Aesha Rasheed: I mostly grew up in a small town north of Oklahoma City. I graduated [high school] in 1995. [My friends and I] knew there was such a thing as gay people, but we didn’t know what that meant fully. I knew a little bit more because my parents had open conversations with me about HIV and AIDS. They told me, “It’s not gay plague. This is what it is.” I was taught a certain amount of tolerance, but that was it.

The first time I saw a black lesbian was in The Women of Brewster Place, a miniseries my mom loved. There’s an amazing storyline of a black lesbian couple and how they wrestle with their identity, a tragic story. I remember seeing that for the first time and thinking, Oh, that’s a thing. But still not being able to say, But maybe I am. It was years, more than ten years, before I understood myself as queer. If I had seen these posters in my high school, I would have known that I could exist—people still tell me that I can’t exist—and that people like me have existed, and they were worth celebrating and not pitying, that I can be black and queer, which didn’t seem possible, and I would have examples of people fighting against oppression. For me, a young black girl, I did not get stories of people changing their conditions. I got stories of downtrodden black folks being treated poorly and eventually somebody, usually a white person, saves them.

David Jack Browning: I grew up in eastern Idaho as a Mormon farm kid and noticed at a young age that I was different from my peers but couldn’t put my finger on it. In the religion they say there’s no such thing as a homosexual. You have homosexual tendencies or homosexual desires. It’s an adjective not a noun. It was drilled into your head that there is something wrong with you. I remember talking to Abram about [my] moving to New Orleans and [he thought] that must’ve been a culture shock coming from a Mormon, conservative, milk-toast homogenous, robotic kind of community, to here where every person is given the opportunity to be celebrated for their differences. I said, “No, I grew up in my culture shock.” When I came to New Orleans it was the breath of fresh air. Having seen that poster of that glorious, flamboyant queen on the wall of my high school, thinking, I can be that too and that is okay, it would have made all the difference because I was trying so hard to disappear.

Abram Himelstein: Just knowing that a language was coming that would humanize more of us would’ve been helpful. In the coming-out conversations that I was party to, I didn’t have the celebratory language. There was a layer of homophobia in South Mississippi and AIDS was another layer. Coming-out conversations were often about helping mitigate what we thought of as being a lifetime of trouble.

Aesha Rasheed: I think about my mom’s response to my queerness. She said, “I don’t know what it means—I’m not sure—are you going to be okay?” She was afraid because she could not imagine a life of joy for me.

David Jack Browning: We’re not here to be tolerated. We’re here to be celebrated.