Literary Belle: An Interview with Janey Hogan

Dillon Raborn interviews Janey Hogan, the creator of a literary journal dedicated to presenting work by Southern women.

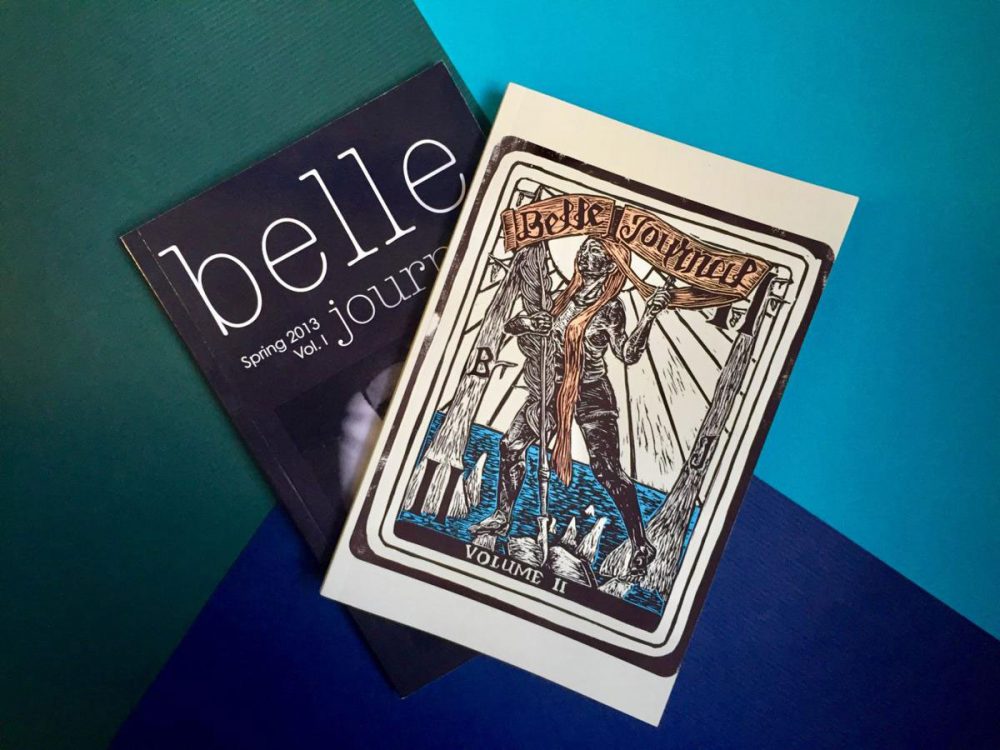

Belle Journal Volumes I and II. Photo by Lauren Heffker.

Editor's Note

Janey Hogan is the editor-in-chief of Belle Journal, a literary journal published in Hammond, Louisiana, featuring poetry, prose, and visual artwork by Southern women. Its premier volume was released in spring 2013, and the second volume—delayed a few years while Hogan worked in Lafayette as a public defender—was released in 2017. Presenting works by young and emerging writers and artists primarily from South Louisiana, Volume II offers a unique perspective on important and timely issues, including abuse, trauma, alcoholism, and other subjects. The journal is co-edited with Amelia Tritico, and contributors to last year’s edition include Heather Cox, editor-in-chief of Ghost Ocean magazine; Amy Susan Wilson, founder of the Red Truck Review; and Katrina Andry (who currently works as Project Manager at Pelican Bomb). Hogan currently teaches law at Louisiana State University and also runs her own firm in Hammond.

—Dillon Raborn

Dillon Raborn: How did the idea for Belle Journal come about?

Janey Hogan: I have a love of Southern women. I was raised by them and I am one. I have all these wonderful girlfriends who are writers, photographers, and other artists, and I really wanted to have a forum or an outlet for their untapped creativity. I also love literary journals. I went to high school at the Louisiana School [for Math, Science, and the Arts] in Natchitoches, and they had this literary journal up there called Folio. I was never the editor but I was on the board for two years and the process of getting submissions, going through them, talking about them, and then arriving at a printed volume was just so much fun.

I was talking with [my friends] and we thought, “Wouldn’t it be cool to have a journal just for Southern women?” After that, it only took a couple of years until it manifested itself. It came about from a love of women and also wanting to deconstruct the stereotype of Southern women. If you do a Google search of “Southern belle,” you get these really gross images of the antebellum time, but there’s such a powerful spirit of women here of all colors, and from all ages and classes.

DR: And they deserve more than Scarlett O’Hara?

JH: Totally! There was this article I read in Garden and Gun magazine [from 2011] about what it means to be a Southern belle. It was this crazy-ass article about how being a Southern woman means we never leave the house with wet hair because that’s “low-rent,” and how our makeup is always perfectly done. I was like, “Are you kidding me? I don’t wear makeup, I cut my own hair on my porch, and I drink whiskey till 7 am.” There are many other women like me and there needs to be an alternative narrative of what a Southern woman is.

DR: It sounds like you’re framing the Southern woman as actually quite masculine. Would you say that?

JH: I would say it’s just ambiguous. I think there’s a masculine/feminine ambiguousness in the South that I really dig. There’s this notion that Southern belles are dainty and kind of fragile, but the majority of women that I know aren’t concerned with having a man in their life to make them fulfilled. Even if they’re in relationships, they still have these very individualistic characters.

DR: In the preface to both volumes you include your title as “Belle/Editor/Tom Sawyer.” Please elaborate on that last title.

JH: Nobody’s ever asked me that question! Have you read The Adventures of Tom Sawyer?

DR: Only Huck Finn.

JH: Tom Sawyer, I think, is kind of my spirit animal because he’s this mischievous little child that tells stories and gets everybody excited about ideas. Tom and Huck are the quintessential Southern children that we all were, essentially, in some way or another, but I started calling myself Tom Sawyer as the journal was taking off. There’s this part of The Adventures of Tom Sawyer in which Aunt Polly is asking him to whitewash the fence before he goes to play. So he convinces everyone in the neighborhood—all his little friends—that painting this fence is the coolest thing ever. All these kids in the neighborhood start paying Tom to whitewash his fence with apple cores and strings and prized marbles. Tom’s just collecting and letting them do this chore for him. When Belle Journal was just starting out, I felt like Tom Sawyer.

DR: Like you were unjustifiably getting marbles from people so they could build this journal?

JH: Not that the journal is a chore, but I was just hyping everybody up, like Ellen [Ogden] who did the cover [of Volume II], or Georgia [Frederick] who looked at photographs all day, and my friend Amanda [Harb] who submitted extra photos. Everybody just believes in this idea because I got them to believe in this idea. They’re the ones painting the fence, and I didn’t do shit except convince them it was a really cool idea. So that’s why I feel like the Tom Sawyer of the journal.

DR: Could you speak a bit about the selection process for entries?

JH: For the first volume we had one selection committee for literary work and another committee for visual work. The committee for literary was completely overwhelmed, so for Volume II we had a poetry committee and a prose committee for about 150 or so submissions. As the editor, I get final veto and I listen to what everyone has to say because I don’t know as much as, say, the MFAs in poetry. And what’s interesting is there’s never been a discrepancy in votes—it’s always been very consensual. I’ve never had to be a tiebreaker. For Volume II we had something like 350 submissions of just written work, so the vote took two days plus some cocktails.

DR: Have you found that submissions come from any particular demographic?

JH: The majority of submissions come from southern Louisiana. Most of the people in Volume I are actually from Baton Rouge, and the majority of Volume II are from southeastern Louisiana and New Orleans. We get some really good jewels from Cajun country.

DR: I couldn’t help but notice a Canadian—Cindy Matthews, from Ontario—included in Volume II. How does the journal define “Southern”?

JH: I think that we’re evolving our definition of Southern. When I was born my family had been here, going back like 200 years, in Louisiana, and I used to have this conception that nobody can say they’re from Louisiana unless they had the same experience as me. And that was very narrow-minded, you know? When I lived in New Orleans I would get bristly at the fact that there were non-locals living here.

DR: You took a great sense of pride in your place?

JH: Yeah, but I think that it was a sort of childish pride, like “this place is mine.” Thousands of people move here every year because they feel something about this place. There is an attraction to the Deep South and southern Louisiana that now makes me proud for a different reason. If you feel the vibe, and if we read your work and we can’t tell where you’re from but it still vibes with the spirit of the journal—displaying a horrific, tragic, ecstatic vision of life as a woman, which is what we’re going for—then to us you’re Southern; you’re one of us. I’m not as interested in biography as content.

DR: Why is it important that we have women-only collections of writing and art today?

JH: I think that everything in our culture is very male-dominated, and I think it’s important to celebrate women. In the past, the Brontë sisters couldn’t get published without male pseudonyms. We’ve come a long way. There was this asshole on my Facebook who messaged me saying, “You’re discriminating against men!” And I don’t really see it that way. Men can totally still submit, and as long as it speaks to us and is in line with what we want to publish, then what’s the problem? We have maybe three or four men in Volume II writing under female pseudonyms, and they can reveal their identities—which some of them do—in the bio section if they really want to. We’re not stealing men’s work and passing it off as some crazy fictional female. But the guys get really into their pseudonyms and craft this wacky bio and roll with it, which is totally fine.

DR: Addressing the antebellum connotations of the Southern belle as a type, the journal’s website explicitly states, “This is not a literary journal which glorifies a Southern myth about demure Southern women.” Is the journal’s existence reactionary towards this?

JH: Since we started in 2013, we’ve seen this [issue] come up more and more. I think that Volume I might have been reactionary to me and my friends’ googling “belles” and getting outraged, but I think Volume II took so long to print because of things like Ferguson and Black Lives Matter, and other subjects that are very dear to me, and here I am, about to publish a journal with the word “Belle” [as the title]...? So, I put the question to Internet forums and asked if it offended people. And people were honest that they were a little offended at first, but understood the message behind the journal which is basically a reclamation of the term.

I want as many people—people of color, [of all] age[s], and class[es]—to feel like this journal is theirs and can belong to them. I want it to speak to them, and I want them to feel comfortable submitting to the journal. And I don’t want it to just be like, “Look at this quirky place called the South where we all run around with bare feet and drink whiskey in the oak trees.” I really want a diverse collective voice of the Southern experience. If I were African-American growing up, I’d have a very different opinion of the South, and I want those to come through in future volumes. If somebody thinks the title of the journal is fucked up and they write us an essay, we’ll totally publish it.