Strange Abominations: “Something in the Way” at the New Orleans Museum of Art

Joseph Bradshaw visits an exhibition at the New Orleans Museum of Art that explores obstruction in photography since the medium’s earliest days.

André Kertész, Paris 1929 (Broken Plate), 1929. Gelatin silver print. Collection of the New Orleans Museum of Art.

Charles Baudelaire’s “The Salon of 1859” contains one of the poet’s most vehement and infamous rants. After complaining about what he considered the blithe acceptance of photography as a legitimate artistic medium, he writes that “our loathsome society rushed, like Narcissus, to contemplate its trivial image on the metallic plate. A madness, an extraordinary fanaticism took possession of these new sun-worshippers. Strange abominations manifested themselves.” Baudelaire’s attitude toward photography borders on philistinism: an odd stance for a pioneer of modernism. But his identification of Narcissus with the photographic image rings true, and it brings to mind a question about what the art public saw in the new medium of photography: What new representational limits and possibilities—or “strange abominations,” to use Baudelaire’s lyrical formulation—were being reflected back at the viewer by this burgeoning art form?

“Something in the Way: A Brief History of Photography and Obstruction” at the New Orleans Museum of Art looks obliquely at these “strange abominations.” The show includes works by photographers from a range of disciplines—including photojournalists, street photographers, studio-based artists, and amateurs alike—who have dealt with the obstruction of their subjects, and the obfuscation of the picture plane. Some photos capture an uninvited shadow, chance reflections, or a photographer’s thumb; others meticulously investigate the optical effects of the camera. Taken as a whole, the works of the exhibition offer a novel view on the limits and possibilities of the medium.

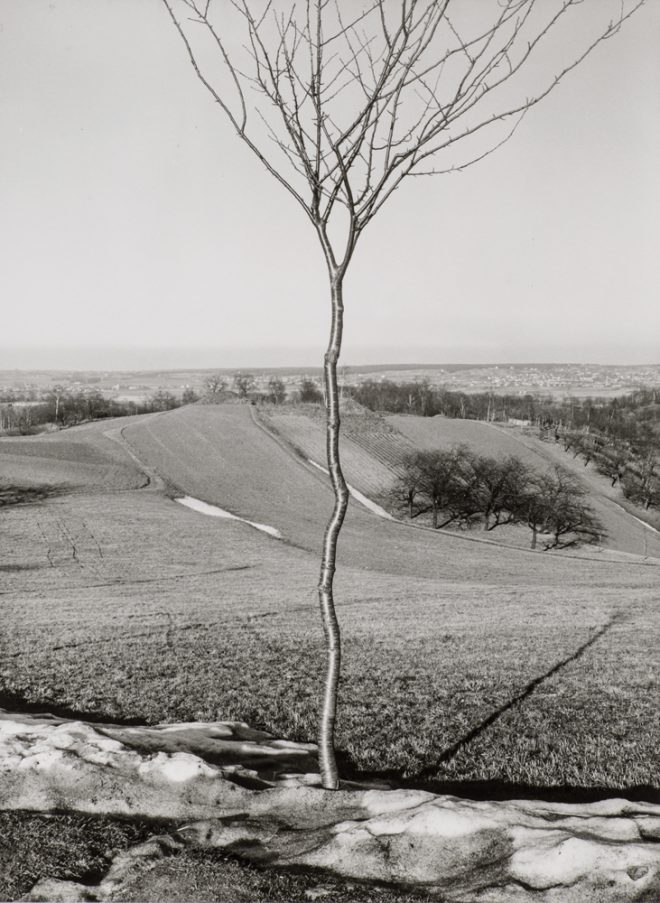

Albert Renger-Patzsch, Das Bäumchen, 1929. Gelatin silver print. Collection of the New Orleans Museum of Art.

Culled from NOMA’s permanent collection, the works on view extend from the earliest days of photography to the present. There are many gems throughout, such as Wendell MacRae’s strange Liner Leaving, 1930, in which one spies the undocking of a giant ship through the windows of a ferry terminal. Between the camera and the liner is a mass of well-wishers gazing toward the ship, their backs to the viewer. The window frames dominating the picture plane look larger than the crowd, which in turn seems bigger than the largest object of all: the almost toy-like liner. Cunningly playing with perspective, the image reads as an homage to the happenstantial cubism of urban life.

It’s a sentiment echoed in Percy Loomis Sperr’s The Peaks Toward Sunset, 1934, which captures the Empire State and Chrysler Buildings through the fenced meshes of the Queensboro Bridge. Through the lens of Sperr—a noted documentarian of New York City street life in the early 20th century—“the peaks” appear majestic. Framed by mesh wire suggesting prison bars, the moneyed power those buildings represent is also as distant as the crests of a mountain range, and as insurmountable.

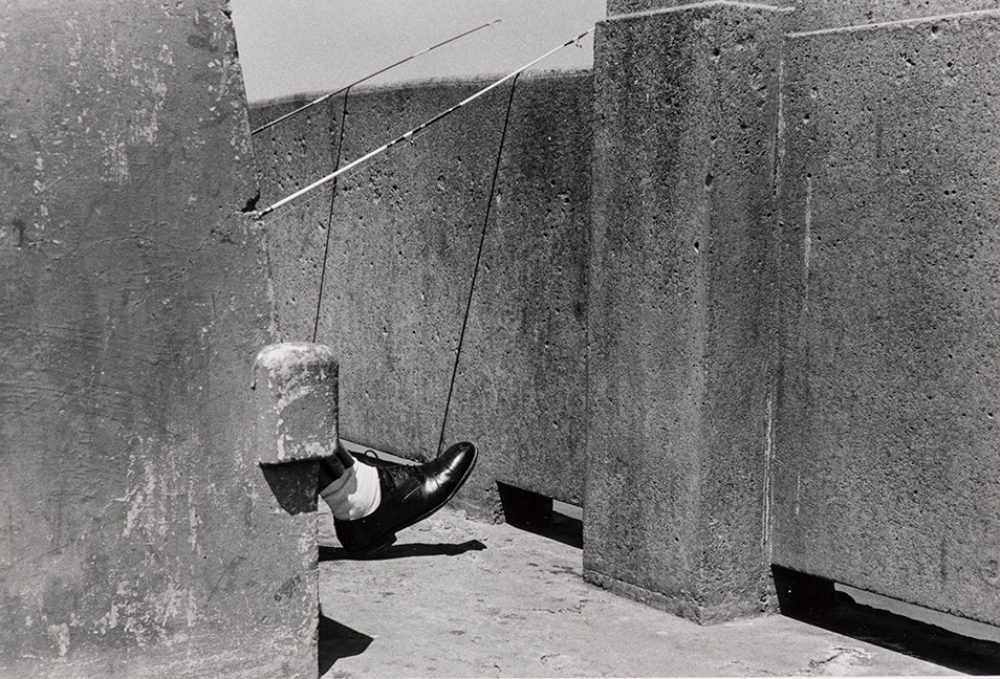

Judith A. Steiner, Untitled (Foot and Concrete), 1981. Gelatin silver print. Collection of the New Orleans Museum of Art.

One of the more sinister works is an untitled series of photos that depicts something closer to the ground, namely the backsides of Lake Michigan beachgoers in 1949 Chicago. Taken at waist level, Yasuhiro Ishimoto caught people standing at the counter of a hot-dog stand, all facing away from the camera. Nearly every butt is wet, caked in fecal-looking sludge. There’s a scatological satisfaction in imagining what is obstructed by the photos’ frames: filthy Americans scarfing down hot dogs. The suggestion of ordure dribbling along the legs of the eaters imbues their unseen (and highly ordinary) actions with repulsiveness.

Another highlight of “Something in the Way” is a group of vitrines of anonymous snapshots taken in the mid-20th century. Each vitrine is arranged thematically: One is dedicated to pictures of people standing behind bushes, another to snaps blocked by the photographers’ thumbs. My favorite vitrine contains about a dozen snapshot portraits; each portrait is obscured by the shadows of their photographers, which hang over their subjects like threats and omens. I gained a lot of pleasure hovering at this vitrine, taking pictures of pictures, capturing in each my own hazy reflection. Though my fragmented image was only a byproduct of the glass protecting the photos, for a moment I glimpsed an apotheosis of Baudelaire’s “strange abominations”: As I walked through the gallery I was suddenly aware of how I, or rather my unintended reflection, added another layer of obstruction to the works in the exhibition. I was in the way.

Editor's Note

“Something in the Way: A Brief History of Photography and Obstruction” is on view through February 19, 2017, at the New Orleans Museum of Art (1 Collins C. Diboll Circle).