GPOY: On Museums, Selfies, and the Self

Charlie Tatum reflects on the use of camera phones to make sense of art and museum spaces.

What does it mean to take a photograph in a museum? I find myself constantly and habitually pulling out my phone. My Camera Roll doubles as a notebook, a shoddily (albeit chronologically) organized collection of snapshots of installation views, details, and slightly blurry wall text. I always try to be sneaky, not wanting to be that person—you know the one—who shuffles from painting to painting, seemingly never breaking eye contact with the viewfinder. That’s what museum-shop postcards are for, right?

But photographs are more than mechanical reproductions. They situate us (the photographer, the viewer) in a place and time: a white-walled gallery, the graffitied bathroom of a dive bar, in front of the Eiffel Tower. Do these relations play out the same whether the lenses of our cameras—or phones, really—are facing outward or flipped back on ourselves? Museums are increasingly allowing photography in their galleries, hoping that the right snap can send historic and contemporary works in their collections viral. The Los Angeles County Museum of Art encourages the use of selfie sticks in its outdoor installations. Art in Island—a recently opened museum in Manila, Philippines—is a simulacral playground designed specifically for visitors to pose with interactive reproductions of artworks.

For those of us who have visited museums often, we’ve been trained from a young age never to touch, that the experience of art should be solely with our eyes. While selfies can indeed pose logistical problems (that nightmare in which you’ve backed into a priceless sculpture), they do allow us to interface with artworks in a new way, to insert ourselves—to touch, so to speak, with our cameras. A selfie serves as a new way of encountering objects, places, and ourselves. My personal records of a few of these encounters follow.

Installation view of Yayoi Kusama’s Love is Calling, 2013, at David Zwirner, New York.

Some artworks seem to be made specifically for selfies and the art market knows this (people stood in line for hours in the winter snow to see themselves for less than two minutes in Kusama’s “infinity rooms”). How can you look at a mirror and not be fixated on your likeness? Am I just vain?

Installation view of “Isa Genzken: Retrospective” at the Museum of Modern Art, New York.

Mirrors manipulate the body, slice it into pieces and put it back together rearranged.

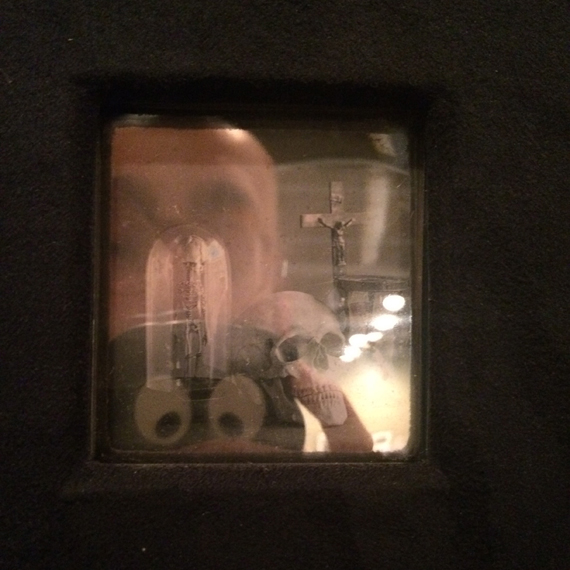

Installation view of Louis Jules Duboscq’s Still life with skull, c. 1850, at the George Eastman Museum, Rochester, NY.

The face and the camera case exist as remnants of a body, reflected and flashed on museum glass.

Installation view of Robert Rauschenberg’s Melic Meeting (Spread), 1979, at the New Orleans Museum of Art.

Is it possible to live inside an artwork?

Installation view of Zarouhie Abdalian’s Chanson du ricochet, 2014, at the New Orleans African American Museum of Art, Culture and History for “Prospect.3: Notes for Now.”

To get the dirt and grime and grease all over your body?

Installation view of Lee Kit’s 3, 2014, at Lombard Freid Gallery, New York.

Other people stumble into selfies all the time, leaving a photographic imprint, a record of human (non)contact. Who is this man?

Installation view of Robert Longo’s After DeKooning (Woman and Bicycle, 1952-53), 2013-14, at Metro Pictures, New York.

Selfies can record moments of interaction, shared experiences filtered through technology.

Installation view of Jeff Koons’ Play-Doh, 1994-2014, at the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York.

I asked Jeff Koons how often people ask for selfies with him, and he said, “all the time,” which makes sense. He didn’t seem real, like he was an illusion of himself.

View from within architect Charles Moore’s Piazza d’Italia, completed 1978, in New Orleans.