Set in the Form of an “S”: Dances for Solidarity in New Orleans

Anna Mecugni writes about choreographer Sarah Dahnke’s ongoing project to draw attention to the injustices of the American prison system through dance.

A performance as part of Dances for Solidarity at the corner of Press and Royal Streets in New Orleans. Courtesy the artist and A Studio in the Woods, New Orleans. Photo by Sabree Hill.

In 2015, New York-based choreographer and cultural activist Sarah Dahnke initiated a collaborative project aiming to reaffirm the humanity of incarcerated individuals in solitary confinement and to reconnect them with the world outside through dance and letter-writing. Supported by Culture Push’s Fellowship for Utopian Practice, Dahnke, alongside a group of dancers, choreographers, and artists, began by devising a ten-part body-mind movement sequence they later shared with people in prison through mail correspondence, inviting them to reinterpret and perform it on their own. Many responded by adding their own movements, at times creating entirely new dance phrases that Dahnke and her team have incorporated into performances outside of prison—thus transgressing the prison system’s complete segregation from society.

The first step of the dance asks each performer to fancy a pleasant space, around and within oneself: “Close your eyes. Imagine the room is filled with light mist, and as you move, the mist collects onto your body, filling it with new, fresh energy. Open your eyes.” The sequence continues with simple body movements, muscle contractions and releases, and mindful breathing exercises. The closing calls for a moment of psychological liberation from the confines of the prison’s cell: “Feel your body grow lighter and lighter, as if you are a cloud. Inhale. Exhale.”

Over the past two and a half years, Dahnke and her team have corresponded with nearly 250 people in prisons across the country, mostly in Louisiana and Texas. (Louisiana is infamously known as the “incarceration capital of the world,” and New Orleans puts people behind bars at nearly double the national average.) Last year, the New Orleans-based residency program for artists and writers A Studio in the Woods invited Dahnke for a six-week stay. She arrived this past April, coincidentally the same week that the Ogden Museum of Southern Art opened the traveling exhibition “States of Incarceration: A National Dialogue of Local Histories,” which aims to foster a national dialogue about the prison-industrial complex. Dahnke’s residency concluded with two public performances on May 9 and 10, presented at the Newcomb Art Museum of Tulane University and at the intersection of Press and Royal Streets. The latter site is a landmark of great historical significance for the early Civil Rights Movement, as it is the place where Homer Plessy, a Creole shoemaker and member of the anti-segregation Citizens’ Committee of New Orleans, was arrested in 1892 for purposefully violating a racial-segregation law dictating use of separate train cars by white and non-white people.

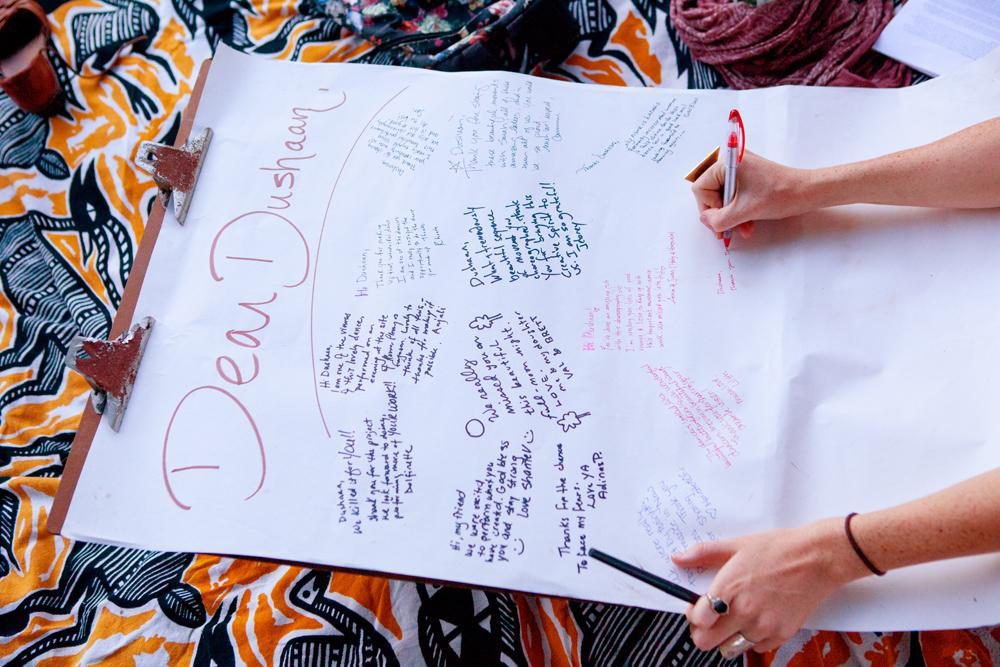

A collective letter to Dushaan Gillum as part of Dances for Solidarity. Courtesy the artist and A Studio in the Woods, New Orleans. Photo by Sabree Hill.

While in New Orleans, Dahnke reached out for the first time to formerly incarcerated people to participate in public performances with Dances for Solidarity. With the help of Dolfinette Martin, who works with Voice of the Experienced, a grassroots organization founded and run by formerly incarcerated people that seeks to promote criminal-justice reform and end mass incarceration, Dahnke gathered a group of five women: Martin, Rhonda Oliver, Adinas Perkins, Shantell Turner, and Latasha Williams. Interestingly, formerly incarcerated women were easier to enlist in the performance than men, whereas women in prison have been difficult to get involved in the project, probably because of fears of receiving disciplinary reports that would make them lose the privilege of seeing their children, as several of the performers in Dahnke’s group noted. Each of the dancers is active in prison-reform advocacy in different ways and all of them are African American, a stark reminder that people of color are incarcerated at disproportionately higher rates than white people.

Dancing to the beat of drummer Boyanna Trayanova, the group presented a performance based on a new sequence created by Dushaan Gillum. Incarcerated since 2002 in Texas and now held in the John M. Wynne Unit in Huntsville, Gillum has been corresponding with Dahnke since the start of the project and conceived this choreography in response to five verbs that Dahnke shared with him: twist, pivot, dart, push, melt. The first step of Gillum’s instructions pays homage to the project and its initiator by striking an “S”:

I begin standing with my left foot planted flat, my right leg is crossed behind my left, and my right foot is at a 90-degree angle with only the tips of my toes touching the floor. My right arm is flat against my side and my left arm is curved over my head as if I’m forming a C. My entire body is set in the form of an S for Sarah, Solidarity and Story.

The five dancers worked with Dahnke to develop choreography incorporating their own responses to the five verbs and bringing together moments of both Gillum’s new sequence and the initial iteration of the dance. After both New Orleans presentations, Dahnke facilitated a participatory exercise, asking the audience to form a circle and guiding them through an enactment of the initial ten steps, which she still uses to invite new collaborators to participate in the project. Following the first performance, the dancers engaged in a remarkably touching question-and-answer session, during which they shared their personal experiences of the tragic injustices plaguing the U.S. prison system. After the second, audience members had the opportunity to write a message to Gillum, who only has access to paper mail.

Dahnke is planning to continue her work in New Orleans. She intends to build on the performances just presented and promote collaborative, educational workshops at juvenile detention centers, high schools and universities, extending the reach of her initiative. Last year, Patrycja Humienik, a graduate student in the Department of Communication at the University of Colorado Denver, started an independent chapter of the project. Dahnke’s vision for Dances for Solidarity is to help create sustainability for any parts of the project that can be useful to its varied participants and to see independent letter-writing and performance-making groups emerge in New Orleans and across the country.

Editor's Note

Dances for Solidarity organized performances May 9–10, 2017, at the Newcomb Art Museum of Tulane University and at the intersection of Press and Royal Streets in New Orleans. An encore performance took place on June 14, after the writing of this piece, at Café Reconcile (1631 Oretha Castle Haley Boulevard) in New Orleans.