A Haunting Mythology: “Atlanta Ladies Memorial Association” at the Zimmerli Art Museum

Following the removal of four Confederate monuments in New Orleans, Dillon Raborn looks at a collaborative project by Rutgers University faculty, staff, and MFA students, which explores memory and mythology in the American South.

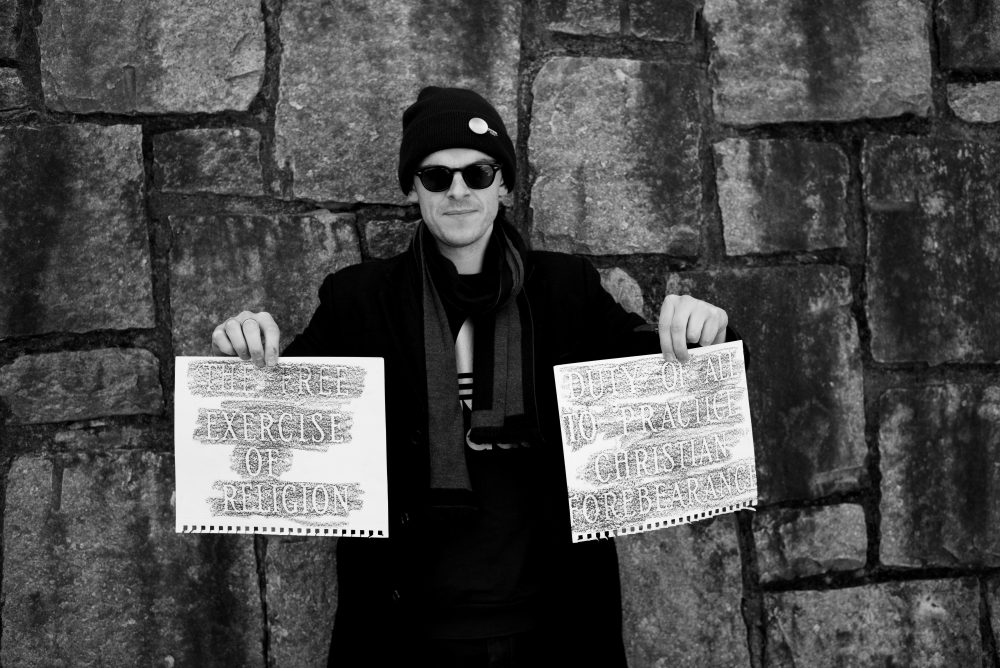

Mason Gross School of the Arts MFA student Jack Hogan, holding frottages from a research trip to Atlanta, Georgia. Photo by Ari Marcopoulos.

The boundary between memory and history can be a blurry one. The difference, we might say, lies in the subjective experience of each. Memory affects us at a direct, phenomenal level, while history does so indirectly and from a distance. Monuments and historic objects can help mediate a healthy relationship between past and present: something we might compare to the mourning process. The archives become catacombs; the historians, wailers. But what happens when the process stagnates? What happens when this distance never emerges, when caskets become reliquaries and memory is transubstantiated into a mythology which haunts rather than enriches the present? The mythology of the Antebellum South reaches deeply into contemporary Southern life, and the still lingering effects of the Confederacy, slavery, and Jim Crow make its past impossible to forget.

“Atlanta Ladies Memorial Association,” on view at the Zimmerli Art Museum at Rutgers University in New Brunswick, New Jersey, is a collaborative art exhibition exploring this tension between history and mythology in the American South. The intimate, archival-based show is the result of a graduate-student expedition to Atlanta led by the artist Kara Walker, the school’s Tepper Chair in Visual Arts. The Rutgers troop—which included students, faculty, and staff who participated in a year-long project and course titled Memory, Memorials and Monuments (MMM)—visited, among other locations: Ebenezer Baptist Church, formerly under the pastoral care of Martin Luther King Jr.; Stone Mountain; Oakland Cemetery; and small-town Franklin, Georgia. The primary subjects of their travels are in the project’s name, and the exhibition serves as an effective index of the group’s experiences in and around Atlanta.

The grandness of a memorial correlates to the will exerted toward an intended narrative. Of monuments to Confederate glory, surely the most bombastic is Georgia’s own Stone Mountain: an unseemly granite deposit emblazoned with a tri-figural equestrian relief of Jefferson Davis, Stonewall Jackson, and Robert E. Lee. Granite has long been imbued with the semiotics of memory in the form of headstones, tombs, and sculptures, but the material’s effect is different—and historically backhanded—for the few occasions it has been granted to slave subjects. As evidenced in a cellphone video installed in the gallery, showing miscellaneous moments of the group’s travels, MMM’s Oakland Cemetery tour led them to one grave marked with the name of Georgia Harris (born 1845; died Feb 5, 1920), the back of whose gravestone reads, “In loving memory of our colored mammy.”

Installation view of “Atlanta Ladies Memorial Association” at the Zimmerli Art Museum at Rutgers University in New Brunswick, New Jersey. Photo by Peter Jacobs.

This phrase, along with various small-relief recordings of the mountain itself and many other granite headstones and memorials are hung as indexical crayon rubbings, littering the walls of the multi-media exhibition at the Zimmerli Art Museum. Most of these dedications wax romantic on the heroism of the Confederacy and visually recall grade-school-level tracings. What would be for children a simple history project becomes a form of resistance and commentary in the hands of artists. One frottage records the words “valor” and “sacrifice,” while omitting the central icon originally christened as such. The result is a neutered glory. Most of the artists have approached their subject matter like archivists, presenting each work neutrally and with little explicit commentary. Postcards of small-town Southern scenery with quaint, red-bricked Protestant churches are hung salon-style in the gallery’s west corner. In the adjacent corner, one piece ushers in a more critical take: A dismounted television screen leads the viewer through Jett Strauss’ CGI rendering of various sacred spaces of Confederate valor, including a digital distortion of the aftermath of the Battle of Gettysburg from director Victor Fleming’s 1939 blockbuster Gone with the Wind.

“Atlanta Ladies Memorial Association” also includes an installation of objects transformed by their found location: a former slave graveyard. The cohort laid these items, which otherwise might be perceived as discarded trash, beneath a glass display in Ziploc bags as collected specimens. Since enslaved Africans were rarely buried with their masters, slave graves, if marked, were, and continue to be, identified by supplies of continuously replenished wood, flowers real and faux, or rock piles, all of which deteriorate as easily as unprotected flesh into soil. When discussing this work, graduate-program administrator Daonne Huff notes, “Ephemera is something to consider in thinking about the fact that within the South we’ve created monuments to losers. How often does that happen? In this context, you’re redefining and rewriting history to the story you want to represent. It is interesting to think about the absence of those who aren’t represented. Why aren’t they? And if they were, how does that change the narrative?” In this context, reparative ephemera are an intervening solution to the often toxic permanence of Confederate memorials.

For four of New Orleans’ most prominent Confederate and Reconstruction-era monuments, ontological deterioration is no longer an issue, with last month marking their removal from public view. As with the loaded sites of MMM’s found ephemera, location is everything. With their permanence eroded, there’s a chance to refine a new identity for New Orleans and, as this trend spreads, a new understanding of Southern history.

Editor's Note

“Atlanta Ladies Memorial Association” is on view through July 2, 2017, at the Zimmerli Art Museum at Rutgers University (71 Hamilton Street) in New Brunswick, New Jersey.