Some Nasty Things: Doreen Garner at Antenna

Charlie Tatum looks at Doreen Garner’s current exhibition at Antenna and contemplates a lineage of abjection in contemporary art.

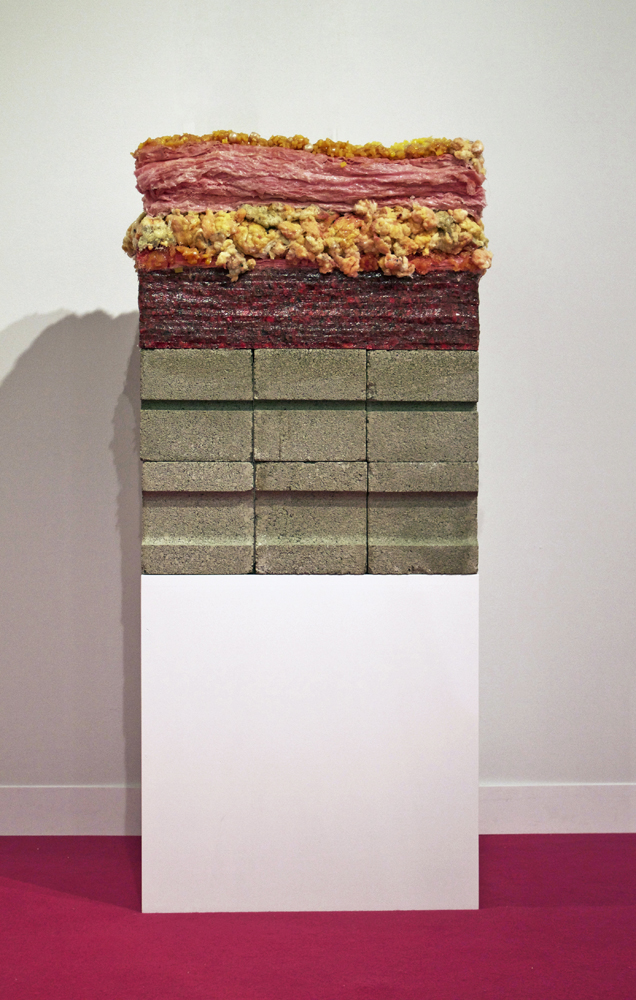

Doreen Garner, Layers, 2016. Mixed media. Courtesy the artist.

I know it’s weird to see a piece of flesh hanging on the wall. I choose the subject matter because it violates my sensibilities, but that’s not the same thing as shock. I work with it to detach myself from it, like a heartbeat.

Paul Thek in a 1966 interview with G.R. Swenson in ARTNews, quoted in Chris Kraus’ Aliens & Anorexia

The first object one sees in “Ether & Agony,” Doreen Garner’s current solo exhibition at Antenna, looks like a meaty slab of flesh. A tower of materials—cinder blocks, pink fiberglass insulation, and something that looks like fruit cocktail—appears as an oversized hunk of skin, muscle, and fat. This work, Layers, 2016, is appealing, yet repulsive; the desire to touch is countered by corporeal nastiness and the fact of human mortality.

Garner’s mixed-media sculptures often reel you in with the glistening of pearls and glitter, only to disgust and disturb with crooked teeth and the violence of needles and staples. A list of materials from a poetic artist statement at the gallery gives a sense of her combination of beauty, pleasure, and revulsion: BANDANAS, STUFFED CONDOMS, PEARLS, CHAINS, HAIR WEAVE, BEADS, DENTURE-REJECTED TEETH, LATEX, MASTERBATORY [sic] GRADE SILICONE, COSTUME JEWELRY, CRYSTALS, GLASS EYES, ZIT-COLORED CABOCHONS, and TAMPONS. These are loaded descriptors, signifiers associating the societal beauty standards for black women’s bodies with the basest byproducts of bodies at large.

Much of Garner’s work looks to this historic relationship between blackness and abjection, emphasizing the horrors of modern medical science inflicted on bodies of color. Vesicovaginal Fistula, 2016, directly references doctor J. Marion Sims’ medical experiments on enslaved women in the 1840s and ’50s at his surgical practice in Montgomery, Alabama, to solve the titular affliction. These attempts to prevent the involuntary leakage of urine through the vagina, a complication of childbirth at the time, labeled Sims the “father of modern gynecology,” but they were only made by possible by widespread views of black women as subhuman, as objects for testing. (Sims later corrected fistulas in white women, only after he felt he had perfected his technique.) In Garner’s sculpture, staples and sutures barely hold together bits of shiny red and brown silicone skin. The sculpture’s mirrored case—which cleverly points to Sims’ invention of a vaginal speculum—gives the viewer a peek at a puckered pink sphincter on the reverse side.

Doreen Garner, Vesicovaginal Fistula, 2016. Mixed media. Courtesy the artist.

More personally, Garner remembers her sister, who had a massive stroke at a young age that caused paralysis and disfeaturing of her face. In a talk at the New Orleans Pharmacy Museum before the exhibition’s opening, Garner noted how the gaze of others can create a sense of dispossession and further abjection, as many people weaponized their stares to reinforce their distance and difference from her sister’s changed face. Saartjie Triangle, 2016, links this intimate family experience to the historical exploitation of Saartjie Baartman, a Khoi woman who was paraded around 19th-century Europe as a freak-show attraction (the “Hottentot Venus”) and whose body was used to scientifically validate racist ideologies rooted in black difference.

During that same talk at the Pharmacy Museum, Garner noted that she sees her work in opposition to the privilege and the whiteness of now canonical abject works by Paul Thek and others. But this dichotomy oversimplifies and ignores the context of Thek’s own production and the ways in which the arc of art history informs our understanding of artistic recognition. Thek not only spent the second half of his career in obscurity, creating unsaleable, ephemeral performances in kunsthalles across Europe while the art market grew disinterested; he also battled AIDS-related complications in his final years, succumbing to the disease in 1988 at age 54.

Though the conditions are different, Garner draws heavily on the simultaneous repulsion and attraction that forms the basis of Thek’s Technological Reliquaries, which display bloody body parts (some recognizable, others not) made out of wax and resin, sometimes with human hair and molded teeth. These disembodied chunks stand in stark contrast to the shiny Minimalist acrylic boxes that house them. (In 1965, Thek even used one of Andy Warhol’s Brillo boxes to enshrine a chunk of meat.) In her 2000 book Aliens & Anorexia, Chris Kraus looks back at Thek’s attempts at transcendence through detachment: “Thek, who was ambivalently homosexual, was arguing for a state of decreation, a plateau at which a person might, with all their will and consciousness, become a thing.” For Thek, thingness became an escape from the overblown subjectivity of the Modern artist, from the horrors of simply being alive in the latter part of the 20th century. Thek’s work has often been read both in the context of the tragedies of the Vietnam War and as eerily prescient markers of the height of the AIDS crisis, during which queer bodies were left to rot en masse.

Garner also highlights the difficulty of thingness, while reminding us that objectification for people of color is not a purely ontological condition. Slavery and colonialism relied on the systematic dehumanization of people—turning people into objects, into things. But Garner doesn’t offer humanization as a response. Instead, she imagines things—bodies traumatized by subjugation and the physician’s knife—as subjects themselves who can confront the viewer with the presence of their own abjection.

When I visited the gallery, a group of high-school students migrated from work to work, and their stampede of steps made the bowels and bling spewing out of Untitled: Bondage, 2016, jiggle with the weight of their feet. The sculpture, an overstuffed lace and hair body bag constrained by ropes to a silver table, seemed to come alive, a haunting reminder of the physical and psychic damage done by white dominance—destruction that can’t be undone but must be reckoned with.

Editor's Note

Doreen Garner’s “Ether & Agony” is on view through November 6, 2016, at Antenna (3718 St. Claude Avenue) in New Orleans.