All That is Solid Melts into Fantasy: Cao Fei at MoMA PS1

Ryan Lee Wong visits Cao Fei’s current retrospective at MoMA PS1 and thinks about how her photography and video works transcend the limitations of bodies and the built environment.

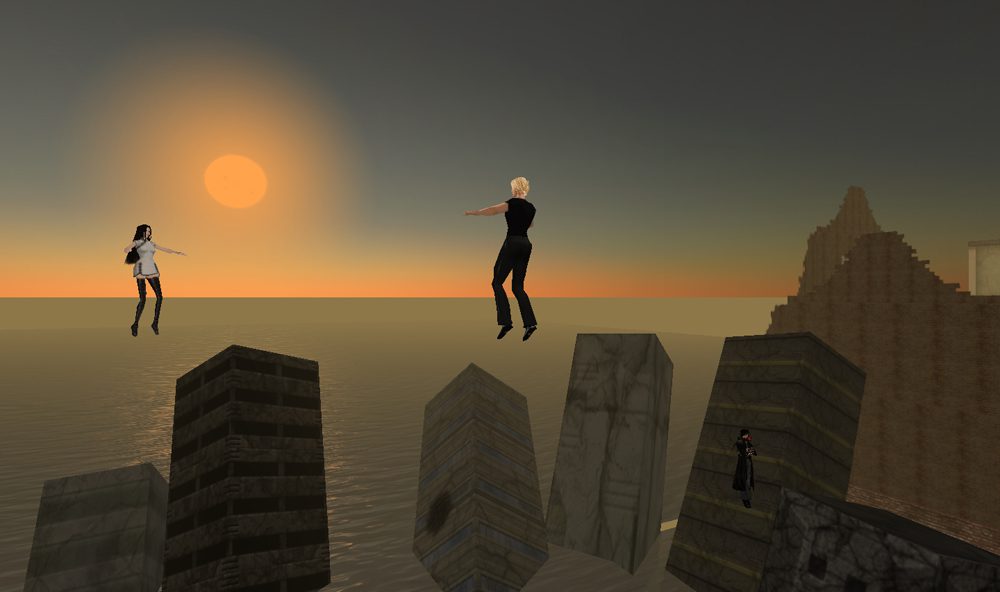

Still from Cao Fei’s i.Mirror, 2007. Machinima video. Courtesy the artist and Vitamin Creative Space, Guangzhou.

In Cao Fei’s work, our physical bodies are deeply limiting. In her film Haze and Fog, 2013, we watch a man struggle to move—the metal legs of his walker stuck between two stones of a cement footpath. Or is it the other way around? Are bodies liberating, like those of the workers Cao films dancing through factory aisles in Whose Utopia, 2006, or the avatar that soars through a cartoonish microcosm of modern China in her RMB City, 2007-11?

Cao was born in Guangzhou, China, in 1978, coming of age as the city entered the great Special Economic Zone experiment, becoming a laboratory for special business and trade laws designed to attract foreign investment and boost industrialization. Guangzhou transformed into a new center of our world economy where the dislocations and transformations of global capital manifested through urban infrastructure, factories, and population boom. (The city’s population has increased nearly tenfold since the ’70s, making it now the third largest city in China.)

Cao builds her worlds inside the shifting spaces of this political and economic landscape—moving between Guangzhou, Foshan, and Beijing; the factory, the housing complex, and the highway; the physical world and digital space. If our current era is characterized by mass migration and diaspora on one hand, and surveillance, policed borders, and privatized space on the other, Cao reminds us that fantasy and memory complicate both geographic and physical boundaries, even as they render them more visible, palpable.

Cao’s first U.S. retrospective at MoMA PS1 in New York (she hasn’t had a museum retrospective in China) begins with her work as a student. Her early films—of art students, BDSM erotics, and humans dressed as dogs—open up inquiries that her later work follows. They show people influenced and constrained by their built environments, finding ways to subvert or overcome them through fantastic and surreal imaginings. In The Little Spark, 1995, a group of performers draws from Cultural Revolution theater to tell the story of two people caught in a robbery, a play on the agitprop of that violent chapter in history, which aggrandized Maoist revolution. The charming Hip Hop: Guangzhou, 2003, looks like a contemporary viral video: A multi-generational cast of people on the street—vendors, parking lot attendants, construction workers—dance to a hip-hop song, traversing American cultural hegemony with smiles and naïveté.

Cao Fei, Cosplayers Series: A Mirage, 2004. C-print. Courtesy the artist and Vitamin Creative Space, Guangzhou.

Fantasy totally envelops the city in her film Cosplayers, 2004. People in anime-style costumes, complete with blue hair and fake swords, run around the streets and buildings of Guangzhou play-fighting for the camera. The quick cinematic cuts and fast-paced electronic music add an energy that allows us to suspend our disbelief as we would with a narrative movie—it almost feels real. That suspension is undercut by quotidian scenes: The cosplayers trudge down crowded highways, and, in an extended montage, lie seemingly dead in abandoned urban areas.

Second Life, the massive online CGI platform that allows users to mold avatars and scenery, was a natural place for Cao to explore built environments and alternate realities. For i.Mirror, 2007, she created a character, China Tracy, who develops a romance with another avatar, Hug Yue. Their conversations are spliced into a pathos-filled 30-minute movie, which takes place entirely in Second Life. “There is a crossover between RL [real life] and SL [second life] as you know. It is hard to separate feelings,” types Hug Yue. Towards the end of the video, the young, blonde Hug Yue asks to update bodies to one “nearer to [his] reality,” and instantly ages 30 years. He is revealed to be a middle-aged white man with graying hair. We wince at the terrible pun of his name, and it’s uncomfortable thinking that Cao/Tracy was manipulating his emotions for the project. But the directness of Tracy’s responses and the unblinking emotions of the film suggest that she is, in fact, making space for his fantasies rather than exploiting them, and taking the opportunity to reflect upon her own. “Is my avatar my mirror?” asks China Tracy, alone in a bathroom.

Whose Utopia brings us back into the physical realm. The film opens with shots of a light bulb factory—the kind that have attracted the camera since film’s first days—with machines pouring glass and bulbs sliding gently from one process to the next. Then, the factory’s workers perform their hidden fantasies for the camera: A ballerina glides past aisles of machines; a rock guitarist shreds while assembly-line workers around him keep their heads down. The film closes with the workers at their stations, confronting the camera, an invitation to imagine them as more than their jobs.

Cao Fei, Whose Utopia, 2006. C-print. Courtesy the artist and Vitamin Creative Space, Guangzhou.

In the live-action Haze and Fog, set amidst the growing housing developments around Beijing, a dominatrix whips a customer, then pauses to answer a text on her phone. A delivery man drops a melon that explodes all over a clean hallway; he halfheartedly tries to clean it up, then continues on with his remaining boxes. In one funny extended shot, a bored real estate solicitor twirls a pointing-finger sign. In the background, a car hits a cyclist. A crowd gathers. The motorist bludgeons the cyclist further with a bat, then drives away. The cyclist reemerges as a zombie and walks right past the disgruntled real estate employee, still indifferent. The film is a grand montage of discontent: Each scene offers characters trapped in stifling social roles and spaces, deciding whether or not to acknowledge the strangeness of their lives.

And Cao’s most recent work in the exhibition, La Town, 2014, surprisingly returns to the analogue. Using plastic toy figurines and a tilt-shift lens, Cao creates miniature, dream-like apocalyptic worlds. A giant octopus is on display, behind rope, in a museum; an airplane crashes near train tracks, where a reindeer pulls a sled. There are scenes of political rallies, of burned and gutted buildings lit by fire at night. A dialogue from the film Hiroshima Mon Amour, reenacted for this work, adds a poetic depth: “I didn’t make any of it up,” says a female voice, recounting her visions. “You made all of it up,” insists a man.

Nothing is more intimate than sharing a fantasy, because nothing is more personal, belongs more to us. Sharing dreams, we open ourselves to ridicule, to that dream’s impossibility. Because of Cao’s ability to elicit that intimacy, even in imagined spaces, her work renders abstract categories of people—“factory worker,” “internet troll,” “fantasy nerd”—visibly human.

Editor's Note

“Cao Fei” is on view through August 31, 2016, at MoMA PS1 (22-25 Jackson Avenue) in Long Island City, New York.