A Man Apart: Reading Lil Wayne’s Prison Journal

Winston Cook-Wilson examines the New Orleans rapper’s seemingly distant and often unemotional account of his time on Rikers Island.

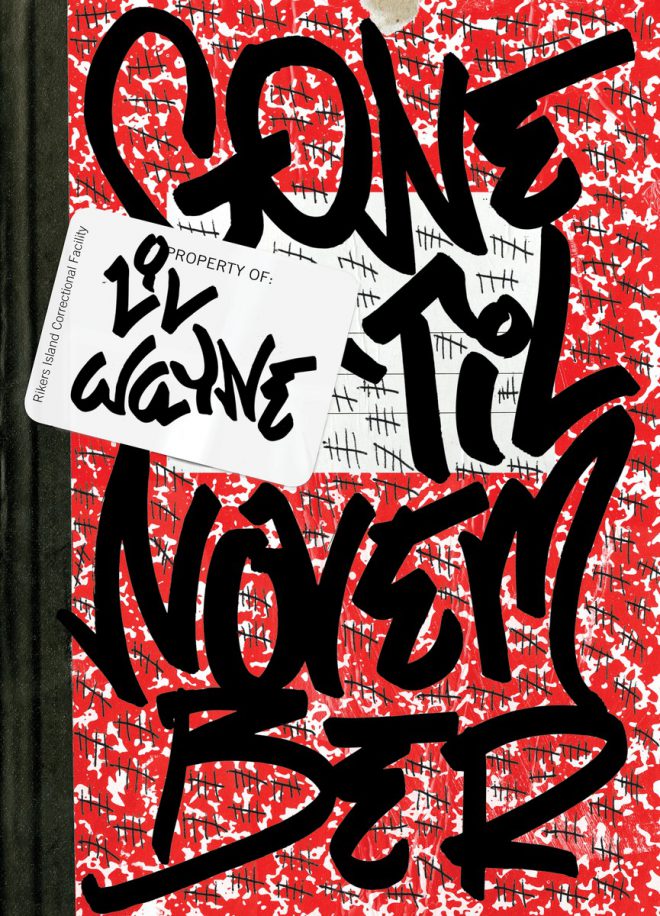

Lil Wayne’s Gone ’Til November was published in October 2016 by Plume, a division of Penguin Random House.

Gone ’Til November, the recently published version of the journal Lil Wayne kept during his eight-month sentence in New York City’s Rikers Island prison in 2010 reads a bit like an annotated day planner. Each page-or-two-long chapter describes the events of a single day during the New Orleans rapper’s time in Rikers, and has the same basic form. They feature precise timestamps, beginning with what Wayne had or didn’t have for breakfast, and ending, usually, with “prayer, Bible, ESPN, bed.” The footnote for each is “Another one gone”—or when Wayne is feeling particularly despondent, just “Another one.”

One might expect a private prison journal to be deeply, even uncomfortably personal, an outlet for expressing frustrations and honest reflection. But in Gone ’Til November, Wayne seems to be aiming for the exact opposite: to remain focused on the day-to-day, and keep negative, demoralizing thoughts at bay, along with overly hopeful ones. He frequently neglects to record some of the bigger developments in his life, and avoids expressing extreme emotions. He gets “news that pisses [him] the fuck off,” but doesn’t provide further detail. He only describes what he does to combat it: pull-ups, watch Martin DVDs, make Ruffles or Doritos burritos. (Chips are the base ingredient for almost any Weezy delicacy.) We get more information about the latest episode of American Idol than his visits from lawyers, “special someone”s, and famous friends—Nicki Minaj, Drake, Kanye, Birdman, and so on.

We hear almost nothing, notably, about his in-house job as a suicide-prevention associate within the prison. Wayne patrolled the hallway of his block until 6 am some nights, listening and watching for cries of despair or torn clothing being tied to a door or stray bar. We hardly hear about the rapper’s feelings about the experience—what he thinks about during his long, lonely shifts. His reticence, however, illustrates how difficult it is for him to maintain his strategy of avoidance; he can only willfully stave off feelings of despair for so long. Eventually, the prison experience pushes Wayne into wanting to disappear entirely for a while, even from himself; at those moments, journaling has no place.

The emotional power of his most noticeable withdrawal—and interruption to the book’s rigid format—is in danger of being overshadowed by its raw newsworthy value for rap bloggers. It comes after Wayne finds out that his girlfriend at the time (unnamed in the book) slept with Drake, his labelmate and protégé. “No writing, prayer, Bible, sleep. Another one” is his entire, unusually brief entry that day. The instigating revelation feels inconsequential to the reader (the Drake affair happened years before Wayne started dating the woman, not while he was locked up), which makes his intense reaction to it—surpassing the despair he expresses anywhere else in the book—more revelatory. Things can mean much more, or something very different, to a prisoner—with so much more time to reflect, caught in an extreme situation—than they might to a person on the outside.

It’s important to note that Wayne’s experience in Rikers was clearly very privileged, especially in terms of the commissary items he would receive and his treatment from guards. The disparity between his situation and that of fellow inmates causes conflict sporadically throughout the book. The tension comes to a head during a recreation break in the yard, when Wayne “gets in the face” of another inmate; a friend steps in to talk him down, and Wayne experiences a humbling moment: “That’s when this dude was like, ‘You go home to something nobody else in here goes home to...He’ll be back in this bitch next month…You’re a millionaire…so act like one!’”

Weezy’s status eventually enhances his feelings of isolation. C.O.s, he claims, transfer to his block just to spy on him. Others divulge the details of his financial solvency (his value appreciating while he sat in jail) to breed animosity against him in his block. Fellow inmates pressure him for access to better lawyers. In a situation where survival is dependent on establishing one’s place in the community and pecking order, Wayne feels like a man apart. He’s increasingly unable to trust or confide in anyone, since to stay alive everyone in Rikers is trying to play the role of “a king, a boss, or a killer.” A piece of his privileged contraband—a watch MP3 player mostly full of Anita Baker and Prince—lands him in “the box” for the final month of his stay after it was discovered during a routine cell search.

Despite its moments of sincerity, Gone ’Til November is designed like a chintzy souvenir, as much suited to a stadium merch table as a Barnes & Noble display: faux-handwritten on lined journal pages, with rows of tallies inscribed within the loops of the graffiti font on the cover. The book will likely disappoint the Lil Wayne fans who might be most disposed to buy it, since it ultimately gives little insight into his inner life during a dark period that interrupted Wayne’s career during a moment of creative, commercial, and critical success. (He has yet to recapture the three at once.) It is interesting, however, as an almost scientifically rendered document of an individual’s experience of prison life in America. Its narrow focus makes it arguably a better book—at least, a more singular one. In Wayne’s clear attempt to hold himself apart from the prison experience, he highlights the penal system’s true essence in a powerful way: its tedious and dehumanizing rituals; its insidious, internal logic.