Poems for Wanderers: Part 1

Poet and Pelican Bomb regular, Benjamin Morris, compiles a selection of poems around our pilgrimage theme.

Cristina Molina, Mother Mist, 2015. Pigment Print. Courtesy the artist and MASS Gallery, Austin.

In one sense, the history of poetry begins with them. Some of Western literature’s earliest major works—the Iliad, the Odyssey, the Aeneid—are accounts of voyages, pilgrimages from one place to another. Troy. Athens. Rome. Later poets such as Chaucer and Dante give us similarly epic journeys, and whether the destination is Canterbury, heaven, or hell, two features of the poetry of pilgrimage stand out. First—old wisdom here—the destination is rarely so interesting as the journey itself: the landscapes crossed, the individuals met, the discoveries made, the marvels encountered. Second, in traveling from point A to point B, the traveler rarely, if ever, remains the same. There is always a process of transformation at work, always a shedding of the old skin for the new.

The act of reading a single poem mirrors the essential act of undertaking a journey, even if the trip is simply from the first word to the last. To celebrate this fact, Pelican Bomb asked me to offer a selection of poets who have all written on the theme in different ways. In what follows, you will find a range of explorations of the idea of pilgrimage, ranging from more traditional interpretations (indeed, a classic hymn to kick things off) to looser, freer approaches that incorporate pilgrimages not as events but as ideas, as stirrings within the soul—including, as later in the selection, the idea of an anti-pilgrimage, or the importance of a good solid wander with no particular direction in mind.

Counter to what your high-school English class might have shown, there is no monopoly on poetic pilgrimages by dead white males who spoke Latin or Greek. Represented here are poets from a range of ethnic and racial backgrounds—African-American, Indian-American, Japanese-American, and Arab-American. Some are from Louisiana, some from the wider South, and others from all across the country. Likewise, these poets are women, men, gay, straight, married, single, agnostic, seeking, and devout, and many of them are very much alive. For the love of poetry, my hope is that this brief summer reading excursion will not only deepen your thoughts on the topic, but that it will furthermore encourage you to make a trip to your local bookstore, and seek out new names and titles that you might not have previously encountered.

Enjoy. And while you’re out there on the road, don’t forget to send a postcard.

“I Am a Pilgrim”

Traditional hymn

I am a pilgrim and a stranger

Traveling through this wearisome land

I’ve got a home in that yonder city, good Lord

And it’s not, not made by hand

I got a mother, got a sister and a brother

Who have gone this way before

I am determined to go and see them, good Lord

Over on that other shore

I am a pilgrim and a stranger

Traveling through this wearisome land

I’ve got a home in that yonder city, good Lord

And it’s not, not made by hand

Now I’m going down to that river of Jordan

Just to bathe my wearisome soul

If I just touch the hem of His garment, good Lord

Then I know He’ll take me home

I am a pilgrim and a stranger

Traveling through this wearisome land

I’ve got a home in that yonder city, good Lord

And it’s not, not made by hand

arr. Johnny Cash, My Mother’s Hymn Book (2004)

“Pilgrimage”

Natasha Tretheway

Vicksburg, Mississippi

Here, the Mississippi carved

its mud-dark path, a graveyard

for skeletons of sunken riverboats.

Here, the river changed its course,

turning away from the city

as one turns, forgetting, from the past—

the abandoned bluffs, land sloping up

above the river’s bend—where now

the Yazoo fills the Mississippi’s empty bed.

Here, the dead stand up in stone, white

marble, on Confederate Avenue. I stand

on ground once hollowed by a web of caves;

they must have seemed like catacombs,

in 1863, to the woman sitting in her parlor,

candlelit, underground. I can see her

listening to shells explode, writing herself

into history, asking what is to become

of all the living things in this place?

This whole city is a grave. Every spring—

Pilgrimage—the living come to mingle

with the dead, brush against their cold shoulders

in the long hallways, listen all night

to their silence and indifference, relive

their dying on the green battlefield.

At the museum, we marvel at their clothes—

preserved under glass—so much smaller

than our own, as if those who wore them

were only children. We sleep in their beds,

the old mansions hunkered on the bluffs, draped

in flowers—funereal—a blur

of petals against the river’s gray.

The brochure in my room calls this

living history. The brass plate on the door reads

Prissy’s Room. A window frames

the river’s crawl toward the Gulf. In my dream,

the ghost of history lies down beside me,

rolls over, pins me beneath a heavy arm.

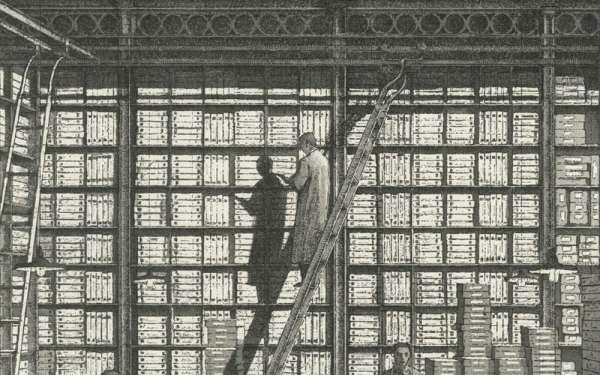

“Self-Portrait with Sylvia Plath’s Braid”

Diane Seuss

Some women make a pilgrimage to visit it

in the Indiana library charged to keep it safe.

I didn’t drive to it; I dreamed it, the thick braid

roped over my hands, heavier than lead.

My own hair was long for years.

Then I became obsessed with chopping it off,

and I did, clear up to my ears. If hair is beauty

then I am no longer beautiful.

Sylvia was beautiful, wasn’t she?

And like all of us, didn’t she wield her beauty

like a weapon? And then she married,

and laid it down, and when she was betrayed

and took it up again it was a word-weapon,

a poem-sword. In the dream I fasten

her braid to my own hair, at my nape.

I walk outside with it, through the world

of men, swinging it behind me like a tail.

“Different Ways to Pray”

Naomi Shihab Nye

There was the method of kneeling,

a fine method, if you lived in a country

where stones were smooth.

The women dreamed wistfully of bleached courtyards,

hidden corners where knee fit rock.

Their prayers were weathered rib bones,

small calcium words uttered in sequence,

as if this shedding of syllables could somehow

fuse them to the sky.

There were the men who had been shepherds so long<br/k> they walked like sheep.

Under the olive trees, they raised their arms—

Hear us! We have pain on earth!

We have so much pain there is no place to store it!

But the olives bobbed peacefully

in fragrant buckets of vinegar and thyme.

At night the men ate heartily, flat bread and white cheese,

and were happy in spite of the pain,

because there was also happiness.

Some prized the pilgrimage,

wrapping themselves in new white linen

to ride buses across miles of vacant sand.

When they arrived at Mecca

they would circle the holy places,<br/k>

on foot, many times,

they would bend to kiss the earth

and return, their lean faces housing mystery.

While for certain cousins and grandmothers

the pilgrimage occurred daily,

lugging water from the spring

or balancing the baskets of grapes.

These were the ones present at births,

humming quietly to perspiring mothers.

The ones stitching intricate needlework into children’s dresses,

forgetting how easily children soil clothes.

There were those who didn’t care about praying.

The young ones. The ones who had been to America.

They told the old ones, you are wasting your time.

Time?—The old ones prayed for the young ones.

They prayed for Allah to mend their brains,

for the twig, the round moon,

to speak suddenly in a commanding tone.

And occasionally there would be one

who did none of this,

the old man Fowzi, for example, Fowzi the fool,

who beat everyone at dominoes,

insisted he spoke with God as he spoke with goats,

and was famous for his laugh.

“Train to Agra”

Vandana Khanna

I want to reach you—

in that city where the snow

only shimmers silver

for a few hours. It has taken

seventeen years. This trip,

these characters patterned

in black ink, curves catching

on the page like hinges,

this weave of letters fraying

like the lines on my palm,

all broken paths. Outside,

no snow. Just the slow pull

of brown on the hills, umber

dulling to a bruise until the city

is just a memory of stained teeth,

the burn of white marble

to dusk, cows standing

on the edges like a dust

cloud gaining weight

after days of no rain. Asleep

in the hot berth, my parents

sway in a dance, the silence

broken by scrape of tin, hiss

of tea, and underneath,

the constant clatter of wheels

beating steel tracks over and over:

to the city of white marble,

to the city of goats, tobacco

fields, city of dead hands,

a mantra of my grandmother’s—

her teeth eaten away

by betel leaves—the story

of how Shah Jahan had cut off

all the workers’ hands

after they built the Taj, so they

could never build again. I dreamt

of those hands for weeks before

the trip, weeks even before I

stepped off the plane, thousands

of useless dead flowers drying

to sienna, silent in their fall.

Every night, days before, I dreamt

those hands climbing over the iron

gate of my grandparents’ house, over

grate and spikes, some caught

in the groove between its sharpened

teeth, others biting where

they pinched my skin.

“Coral Road”

Garrett Hongo

I keep wanting to go back, across an ocean, blue-gray and uncaring,

White cowlicks of waves at the continental shore, then the midsea combers

Like white centipedes far below the jetliner that takes me there.

And across time too, to 1920 and my ancestors fleeing Waialua Plantation,

Trekking across the northern coast of O’ahu, that whole family

of first Shigemitsu

Walking in geta and sandals along railroad ties and old roads at night,

Sleeping in the bushes by day, ha’alelehana—runaways

From the labor contract with Baldwin or American Factors.

My grandmother, ten at the time, hauling an infant brother on her back,

Said there was a white coral road in those days, pieces of crushed reef

Poured like gravel over the brown dirt, and, at night, with the moon up,

As it was those nights during their flight, silver shadows on the sea,

It lit their path like a roadway made of dust from the Ocean of Clouds.

Michiyuki is what they called it, the Moon Road from Waialua to Kahuku.

There is little to tell and few enough to tell it to—

A small circle of relatives gathered for reunion

At some beach barbecue or Elks Club veranda in Waikiki,

All of us having survived that plantation sullenness

And two generations of labor in the sugar fields,

Having shed most all memory of travail and the shame of upbringing

In the clapboard shotguns of ancestral poverty.

Who else would even listen?

Where is the Virgil who might lead me through the shallow underworld of this history

And what demiurge can I say called to them, loveless ones,

through twelve-score stands of cane

Chittering like small birds, nocturnal harpies in the feral constancies of wind?

All is diffuse, like knowledge at dusk, a veiled shimmer in the sea

As schools of baitfish boil and revolve in their iridescent globes,

Turning to the olive dark and the drop-off back to depth below,

Where they shiver like silver penitents—a cloud of thin, summer moths—

While rains chill the air and pockmark the surface of the sands at Sans Souci,

And we scatter back inside to a humble Chinese buffet and cool sushi

Spread on Melamine platters on a starched white ribbon of shining cloth.

Editor's Note

For the second half of the poems selected by Benjamin Morris, visit Part 2.