Olfactive Memory: The Locale of Scent

Laurence Ross visits Hové Parfumeur in the French Quarter and explores the art of perfume-making as it relates to desire and identity.

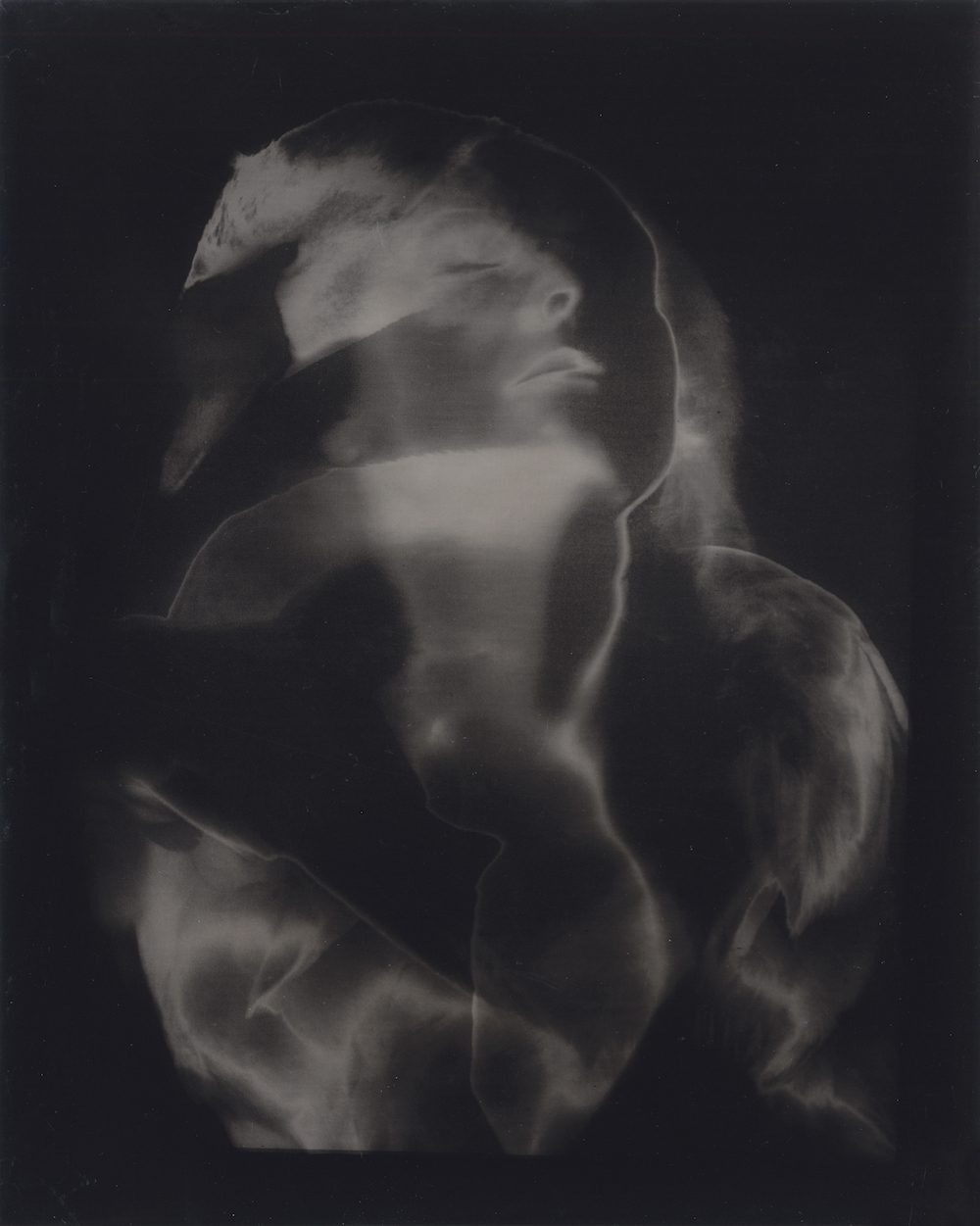

Josephine Sacabo, Leda and the Swan, 2014. wet collodion tintype. Courtesy Josephine Sacabo Photography.

For perfume to be recognized as a form of artistic expression, criticism is essential.

Jean-Claude Ellena, house perfumer at Hermès

The act of walking into a perfume shop feels like an antiquated action. Taking the step in seems to move one backward, toward another time. At Hové, located on Chartres Street in the middle of New Orleans’ French Quarter, the space is not too different from the original perfumery owned and operated by Mrs. Alvin Hovey-King in the early 1930s. The shop is filled with wooden cabinets, glass front doors, neat rows of tiny bottles, large canisters of raw ingredients, and thin strips of white paper on the long countertop, each anointed with a dab of oil identified by its scent for the well-acquainted or its label for the novice. Hové is a family-run business with each owner living in the quarters above the shop. And, though the job of the perfumer may seem outdated, as much a relic as the antique bottles, pumps, and trays that provide a nearly church-like atmosphere, the act of crafting a new scent remains as challenging, vexing, and surprising today as ever.

In his book Perfume: The Alchemy of Scent, Jean-Claude Ellena, head perfumer at Hermès, deftly aligns his profession with that of any artist in a single sentence: “Because to create is to choose.” Perfumery involves selection and amplification, manipulating the senses with the same base strategies employed by painters, sculptors, photographers, dancers, musicians, and writers. A perfumer must focus the attention of his audience and risks the selfsame attraction or repulsion, understanding or confusion. As Ellena says, “The strategy is to embody intoxications, fantasies, and passions through signs and symbols, and to create an object of desire.”

If the artist is one who makes a desire concrete, then the perfumer only accomplishes this task fleetingly. Perfume is about making an impression, one that begins to dissipate from the moment the oils are atomized. Perfume can be savored but certainly not held. (Perfume is, after all, invisible.) Art preservationists continually strive to keep paintings shielded from light, to keep color intact, to keep art stable in a way that goes against the nature of any medium. The word medium implies a transition, a transient moment, a fleeting fancy, and in this way, perfume may be the Platonic ideal. While a musical score can be recorded or a stage performance captured on video, the scent of a perfume can linger on the body only for a matter of days, sometimes hours.

My initial attraction toward perfume as an art critic began with my usual interests, my default settings—the experiential and the participatory. I longed for the experience of the perfume shop: to hold the bottles, to read the cryptic labels (SYR.PICIS.L., BOL.ARMEN., POT.CHLORAS.), to feel the scented oil swirled on the underside of my wrist by a glass dropper, to listen to what the other customers would say, to move through the space slowly, museum-like, to take it in, to be a part of it. Scent was not exactly an afterthought, but it was, merely, a thought. Originally, the idea of scent held more potency than scent itself. As an intellectual concept, trying to write concretely about what is invisible is a challenge, solidifying the fact that my impulses were well-rooted in the wrong sense for the job—the visual.

Speaking with Amy van Calsem-Wendel, the current owner of Hové, she readily concedes that the look of the shop itself is integral to the perfumery. The pinks of the ribbons and walls glow at night, set off against the dark woods of the cabinetry and the glint of the bottles.

“Smell is the mute sense, the one without words,” says Diane Ackerman, author of A Natural History of the Senses. While Ackerman’s declaration that smell lacks a vocabulary is debatable, there is definitively a language to the field of perfumery: chypre, fougère, concrete, absolute. Headspace is a technique for identifying and analyzing odors, and though the technique boasts objectivity, the name alone betrays an inherent subjectivity—for who can fully enter the headspace of another?

Van Calsem-Wendel has curated a physical space that offers something close, a storefront that invites the pedestrian to step in off the street, to enter her headspace. Her bottles atomize and spread scent: lavenders, ambers, jasmines, honeysuckles. The windows of Hové trigger nostalgia, even if we are longing for a past that was never ours. The interior of the shop is mannered, the orderly aesthetic of the bottles and blotters contrasts the promise of romance and the prominence of the past. Reframed in an art gallery, we would view the counters and cases of the perfumery as cabinets of curiosities rather than gross commerce. Wunderkammer, a gathering/sorting/arranging of objects that has interested artists from Max Ernst and Joseph Cornell to Peter Blake and Damien Hirst. Upon entering Hové, our daily reality is curtailed, disrupted, agitated in the fashion Wordsworth found integral to the cultivation of ideas through art.

Van Calsem-Wendel says that in the business of fragrance, one must spend time with the person on the other side of the counter. A perfumer must grow to understand an aspect of the client so that she may align that aspect with a scent that would be harmonious, that would compliment. There is an implied intimacy between perfumer and customer—and this intimacy necessitates patience, the same patience required to understand any body, anybody, any body of work. To her, the notion of creating a custom scent in an hour—or even a day—is an impossible task. To create a scent that accurately represents the whole of a person takes years. Rather than create a perfume for each individual customer, Van Calsem-Wendel begins with the image of a person, specifically a New Orleanian, blending and tinkering until the scent and that imagined persona are seamless, whole, complete. (And perhaps here the art critic’s initial impulse toward the visual is not as far off as it first seemed.) Her aim is to have the person suggest the scent and, in the end, the scent suggest the person. This process remains much the same as when Hové began nearly a century ago, when Mrs. Alvin Hovey-King made her first fragrance (Carnaval®) in 1927 for a friend. Learning just how exactly those bottles might mix and coalesce into an individual, a sense/scent of self, demands patience—the patience required of any artist. As Ellena says of the perfumer: “You have to be ready to try and fail over and over again.”

Josephine Sacabo, La Desdichada, 2014. wet collodion tintype. Courtesy Josephine Sacabo Photography.

A perfume bottle allows us to spritz as we please. A scent that stirs us can, as Ellena notes, “be renewed constantly through a single gesture,” the simple press of a fingertip. A gesture—or a scent—as distinctive as one’s gait, is a portal into personality. Scent has a movement, a certain aliveness, that an object at rest must strive harder to convey. A scent can stir, and perhaps more easily than any other art form, as the sense of smell can transport us so quickly to another place, another time. This transportive quality of perfume is why Hové has kept the core substances of their line a constant all these years, the vetivert and verveine and tea olive as rooted in the history of New Orleans as the names of the scents they inspire: Bayou D’Amore, Belle Chasse, Rue Royale®.

Scent, our most animalistic sense, is also the one most explicitly tied to what distinguishes each of us most, what makes us most human, most other—our minds. It seems no small tragedy that we do not devote nearly as much of our studies to enhancing our olfactory capabilities. We enhance our abilities to listen for variations in song, see gradations of color, taste for subtlety, feel for texture, comprehend nuance of thought. Scent—perfume—is more often than not perceived as superfluous, an adornment, an expensive pleasure only the wealthy might afford rather than a medium through which we wander from place to place, locale to locale, discovering the scents we wish to inhabit, or the scents we wish to seek out again, an invitation to an enriching and luxurious world.

Ellena draws a jarring distinction between pleasure and luxury. “Pleasure is selfish,” he writes. “Luxury is something you share.” According to this philosophy, Marilyn Monroe’s famous gesture of wearing Chanel No 5 to bed would be a selfish pleasure if she were sleeping alone, a generous luxury if she were to go to bed with another. The latter transforms the gesture into a shared gift, an intimacy. And, due to the invisible nature of perfume, it is a luxury unlike most. Luxury, here, does not mean large or even material. Here, luxury means nearly the opposite of space, a closeness, of being close enough to distinguish the nuance of scent, to relish that brief moment of intimacy we must work to stay conscious of, that ever-changing yet ubiquitous present.