Increase the Peace: "Guns in the Hands of Artists" at Jonathan Ferrara Gallery

Nathan C. Martin reflects on the Jonathan Ferrara Gallery exhibition, "Guns in the Hands of Artists," and its relationship to the NOPD gun buyback program.

Installation view of works in "Guns in the Hands of artists" at Jonathan Ferrara Gallery. Courtesy jonathan Ferrara gallery, New Orleans.

During the opening weekend of Prospect.3 in October, Kirsha Kaechele gathered a bevy of musicians, dancers, and other agents of revelry under the auspices of hosting a public gun buyback in St. Roch in partnership with the New Orleans Police Department. The event was also a very public re-emergence into the local art scene for Kaechele, who left town in 2011 under controversial terms. She had earned a reputation as a brazen opportunist, and upon leaving for Tasmania with her ultra-wealthy beau, she abandoned a row of derelict houses on North Villere Street she had previously used for art functions, leaving them to rot.

The event was pretty whatever. Handfuls of people cycled in and out, but besides the performers the mood seemed stilted. Eventually, it produced a few guns, which smelters whom Kaechele had brought from Tasmania melted down and formed into what one bystander said looked like “a little piece of junk.” It seemed to surprise no one that a person who proclaimed “I see myself as a life artist … Life is the medium I most often work in” would engineer a grand extravaganza allegedly meant to be a stroke against gun violence but that mostly ended up publicizing herself.

Scholars who study the effectiveness of gun buyback programs in deterring violent crime overwhelmingly conclude that they are essentially worthless. There are far too many guns on the streets for such efforts to make any real difference, and those who are likely to use their guns—or have used their guns—to shoot people are unlikely to sell them (particularly to the cops). Imagine trying to combat obesity by hosting a cupcake buyback.

A couple weeks prior to Kaechele’s event, another art show opened in New Orleans that also aimed to address gun violence. It also included a gun buyback component, and its public kickoff also involved a smelter melting down weapons—this time into a sewer cover. The exhibition, “Guns in the Hands of Artists” at Jonathan Ferrara Gallery, invited 33 artists to use decommissioned guns collected via NOPD buybacks to use as material in artworks that comment on “the issue of guns in our society.”

Though Ferrara hosted his first "Guns in the Hands of Artists" exhibition in 1996, the redundancies between these two projects suggest something other than a mere lack of imagination. It is more likely a reflection of the simple fact that a Julia Street gallery owner and a second-rate millionaire art star are so far removed from the realities that create the conditions for gun violence to thrive that efforts on their part to address the issue, earnest or not, will produce staid thinking and lackluster results.

An overarching theme in “Guns in the Hands of Artists” might be characterized as: “Golly, I wish we could just turn guns into [insert something nicer to think about than guns].” Paul Villinski’s submission transformed a pistol and a rifle into metallic butterfly habitats. Luis Cruz Azaceta’s Carousel intermixed toy gun parts with real ones and hung them from a mobile. Ron Bechet’s Swords to Ploughshares references a Bible quote in which God encourages nations to turn their weapons into nonthreatening objects. Jewelry maker Nicholas Varney crafted a solid gold bullet with a tip crusted in diamonds, which he put next to an ugly old gun. Skylar Fein retrofitted a shotgun into a bong.

The go-to counterargument against scholarship that deems gun buybacks useless is that, as public events, they at least can create dialogue and discussion. But discussion among whom? The piece in Ferrara’s exhibition that best answers this question is a sculpture by Montreal-based artist Michel de Broin. De Broin’s artwork doesn’t address the conditions in a place like New Orleans that breed gun violence, but it reminds the viewer of a crucial factor that must be present for one human to convince another not to kill: connection. His sculpture is simply two forearms and hands, rendered from bronze and coated flat white. One grips a pistol while the other, belonging to another body, reaches out to gently touch the gunman just above the wrist. It’s a knowing touch, but one can envision it taking place between two strangers. The gesture exudes compassion and empathy, not for any would-be victim, but for the would-be shooter. It stands in stark contrast to the way our society and justice system treat those who would take a life: As many people as we crush with incarceration, the killing doesn’t stop. It also seems to state, in quiet, elegant terms: To stay a man’s hand, you must know him well enough to love him like a brother, and he must know you well enough to trust you as a friend.

Very few of the artworks in the exhibition communicate anything about gun violence that suggests this degree of intimacy, this sense of compassion and understanding. Those within the “Golly, I wish …” camp—which includes Ferarra’s own contribution, a shotgun lodged in a stone à la Excalibur—seem clueless as to how to even begin. But one component of the show does manage to create public dialogue among people who have deep, firsthand experience with gun violence in New Orleans.

Installation view of works in "Guns in the Hands of artists" at Jonathan Ferrara Gallery. Courtesy jonathan Ferrara gallery, New Orleans.

Ferrara told me that his point person for acquiring decommissioned weapons from the NOPD, Earl Johnson, had asked him at one point: “So, you’re doing this gun thing in this white gallery down on Julia Street. What are you going to do for the kids in the hood?” Ferrara thought about it for a few days, asked around, and was eventually put in touch with Melissa Sawyer at the Youth Empowerment Project. YEP began in 2004 as a reintegration program for New Orleans youth coming out of juvenile detention, but has grown to offer a wide variety of mentoring, tutoring, and development support for at-risk young folks. Ferrara and YEP came up with a docket of four panels to take place during the show, one each month from October to January, that discuss gun violence from multiple perspectives. After watching the first two panels (they’re available online here and here) and spending time with the exhibition, the gulf between the art world of which Ferrara’s gallery is a part and the world in which gun violence predominantly takes place in New Orleans became even more pronounced. Those panel discussions were excellent, and the videos of them are important documents. The work of the panelists—particularly from the first panel, which gathered leaders of organizations that engage at-risk youth—is nothing short of heroic. To watch a group of such caring, intelligent, dedicated people talk about what they do, and then to think about how little progress has been made at-large, suggests the scope of the brutal, uncaring system they’re operating against. Ferrara should feel humbled and grateful to have hosted them in his gallery. To his credit, he was the one who invited them.

Again and again, the youth organization leaders—Jim Kelly from Covenant House, Sawyer and August Collins from YEP, Leslie Richardson from the Institute of Women and Ethnic Studies, and Minh Nguyen from VAYLA—stressed the importance of understanding acts of gun violence within the context of the environment in which the people most often affected by it live. They articulated a world where the young people most likely to shoot or be shot—predominantly African-Americans from low-income families—are embroiled in a daily struggle for psychological, economic, and basic physical survival. The children they describe are hungry—literally—and worry most about housing, food, and safety. They are traumatized without access to mental health services. Guns are easy to get, while jobs are not. In a society that devalues their lives and minds, guns are a means of power and control. The panel on December 17 included people working at the policy level to stem gun violence. One of Lisa Richardson’s statements provided an apt preamble: “The society we adults have created for [these children] has failed on so many levels.”

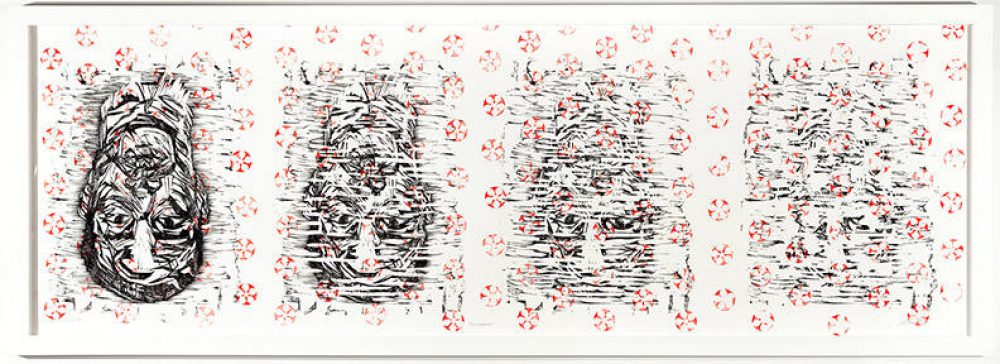

The artist Katrina Andry’s contribution, Disappear, offers one of the most direct, nuanced approaches to visualizing this context in the exhibition—a monoprint of a black man’s face repeated three times that fades with each iteration, from left to right. The faces are overlaid by dozens of red prints made from the cylinder of a six-shooter. The men her work refers to disappear as they are killed, imprisoned, or as their humanity is obscured by the stereotype that all black men are violent. “Our society is mostly scared and suspicious of black men,” she writes in her artist’s statement, “and not really caring if they disappear, whether it’s by the gun or by indefinite jail time. Who cares if they disappear?” This statement and her artwork speak to Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man: “I am invisible, understand, simply because people refuse to see me … When they approach me they see only my surroundings, themselves, or figments of their imagination—indeed, everything and anything except me.” Andry’s rhetorical question, “Who cares if they disappear?” echoes the protest refrain in the wake of the non-indictments of the police officers who killed Mike Brown and Eric Garner: BLACK LIVES MATTER.

Katrina Andry, Disappear, 2014. Monoprint. Courtesy the artist and Jonathan Ferrara Gallery, New Orleans.

At the other end of the spectrum is a piece that, at a glance, looks a lot like Andry’s but has the opposite effect. One Hot Month by Generic Art Solutions, the moniker for local art-duo Tony Campbell and Matt Vis, actively works to decontextualize gun violence and fortify the stereotypes that reinforce it. The work is an arrangement of blown-up photographs from obituaries of 27 people who were murdered in New Orleans during the month of August 2002, with silhouettes of guns overlaid on top of them. Removed from the context of their obituaries, which describe them in loving terms, these actual human beings—as opposed to Andry’s symbolic black man—are rendered anonymous, leaving the viewer simply to stare at a repetition: black person and a gun, black person and a gun, black person and a gun. The victims’ context and their humanity have been disappeared. GAS’ artists’ statement conjures the specter of the violent black man while refusing to acknowledge any outside factor that might encourage gun violence—besides the “sweltering summer months in New Orleans [when] tempers flare”—or contribute to “our broken society threatened to be held captive by the increasingly impulsive actions of heavily armed and troubled youth.”

The morning of the gun buyback for “Guns in the Hands of Artists,” to which Ferrara pledged to donate ten percent of the exhibition’s sales, I drove over to the community center in Central City where it would be held to see how it would go down. It wasn’t supposed to be a spectacle like Kaechele’s, but I was surprised to find that no one was there. Literally no one. The doors and gate were shut, the parking lot empty, the lights inside off. I sat there in confusion for a long time, double-checked the date and location, left and came back. Nothing. At one point, a man with a gray beard arrived in a sedan and emerged with a handgun-sized object wrapped in a plastic grocery bag. He tried the doors and peered through the windows, walked around the building a couple times, and eventually took off.

Ferrara later told me he’d called the NOPD a few days in advance of the buyback to make sure everything was in order, and they told him that the event was canceled, offering little explanation. Ferrara was incensed. He rescheduled the buyback for January, this time through the Metropolitan Crime Commission. The NOPD did not respond to my repeated requests for comment.

If gun buybacks are meant to take guns from the hands of people who would use them for violence, one could do better for a partner than an organization whose members routinely kill people with guns under the protection of a corrupt, racist legal system. The New Orleans Police Department is a national disgrace, even in a nation where it seems an ongoing debate is taking place as to whether a police officer who kills an unarmed black man can be punished by our laws. The NOPD has long been a model of murderous abuse whose crimes should disqualify it from operating autonomously at all. The department and the legal apparatus that at once protects killer cops and incarcerates more people than anywhere else on the planet lack the moral authority to ask anyone to hand over their weapons.

Editor's Note

"Guns in the Hands of Artists" was on view October 4, 2014 - January 25, 2015 at Jonathan Ferrara Gallery (400a Julia Street).