Birds of America

Andrew Berardini revisits John James Audubon's naturalist classic, The Birds of America, with a series of short narratives.

“I call birds few, when I shoot less than one hundred per day.”

—John James Audubon, letter to G.W. Featherstonhaugh, December 1831

John James Audubon, Great Northern Diver or Loon From The Birds of America, 1827-38. Courtesy audubon.org.

1 Common Loon (Great Northern Diver)

Gaviiformes Gaviidae Gavia immer

These are not birds, they are paintings made into prints. A collection of lines and colors, but still they move. Or most do. Some are stuffed and dead, rush jobs to complete the catalogue, but others swoosh and bound, beautiful in their liveliness by any measure.

The arcing neck of this loon laughs maniacally. A zebra patchwork of black and white laces up its body, banding its neck. That deepest teal of its head and its black-tipped tongue make this creature look mad, some lunatic aristocrat ordering mountains to weep and oceans to surrender. Its single glassy eye an unsubtle reminder that birds were once dinosaurs, cold and ancient and always hungry, even if it’s now only just color and lines.

The setting is classic Audubon even if he didn’t usually paint them himself, a soft focus background of blues and grays, the greenish brown grass painted with muted shades, made faded, like root beer and old moss. The loon sharply foregrounded, vivid as hell.

The Birds of America were prints sold by subscription, often by the artist himself playing the rugged outdoorsman with long hair and a buckskin suit. Originally published between 1827 and 1838, they were first sold to the wealthy, though no later more affordable editions came out that were a kind of middle-class art for those that could not afford paintings but still cared to decorate their houses, not with things they might make themselves or religious iconography (as working folk do), but with secular celebrations of nature, which at the time was in the process of being conquered. Despite its stolidly middlebrow appeal, amongst the first subscriptions of complete sets went to kings of Great Britain and France.

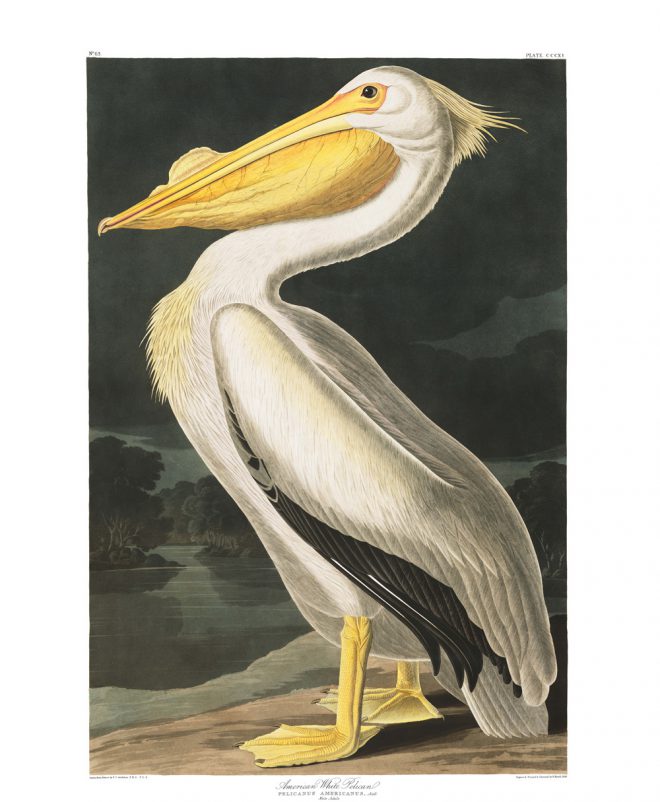

John James Audubon, American White Pelican From The Birds of America, 1827-38. Courtesy audubon.org.

18 American White Pelican

Pelecaniformes Pelecanidae Pelecanus erythrorhynchos

What a regal bastard.

His cracked bill, the deep curve of his neck and the long slope of his back. Those snowy white feathers so stark against the subtle shadow, the darkness of the still waters and storm-black clouds above. The tuft on his head and the tuft on his chest like the last wisps of hair on some ancient mariner, survivor of a thousand storms and a hundred shipwrecks.

Despite whatever love for ornithology might exist in France, the Rue de Pelican in Paris was originally Rue du Poil-au-con, Street of the Cunt Hair. Other streets worked by prostitutes included Cock-Pull Street, Fuck Nun Street, Ass Scratch Street, and Give Joy Street, all equally corrupted or disappeared in modernity. Though far from the sea, weary sailors always had an affection for such streets. The pelican got its name for some reason from the Greek word for “axe,” but I find more nobility for this old seabird in cunt hair.

John James Audubon, Frigate Pelican From The Birds of America, 1827-38. Courtesy audubon.org.

28 Magnificent Frigatebird (Frigate Pelican)

Pelecaniformes Fregatidae Fregata magnificens

This magnificent bird is not a bird, but a burst of energy, a collection of angles, a stark black surge of lines across the whiteness of the page, all flowing down into the narrow neck. The red throat, unpuffed, the eye rimmed with ultramarine and fading into its pale beak curved into a point like a claw, though surreally its actual claws hang disembodied in the sky.

I do not understand the lines of its body, the anatomy attempted, the scientific value of categorical index of all living things, murdered and mounted. I could not shoot this creature from the clear seasky. On the page, I can finger its curves, an abstraction from nature more beautiful than any common figure, more alive than any taxidermied hide.

John James Audubon, Purple Heron From The Birds of America, 1827-38. Courtesy audubon.org.

33 Reddish Egret (Purple Heron)

Ciconiiformes Ardeiade Egretta rufuscens

A couple of lank widows egress from their carriage, each slender leg arced out from the door and onto the cobblestone street at the steps to the opera house. They stand, each glancing in different directions at the other sumptuously appointed ladies shimmering in their silk sheaths and cascading gowns. Parsing the flock for any single, foreign gentleman dashingly jacketed and silkily tied, they jerk their heads, this way and that, impatiently waiting for their valet to close and latch the door behind them.

The grand Madame M., arrayed in white, rests her chin on her corsetted breast, pinched and strapped into some architectural wonder, delicately feathered. The dowager Duchess steps across the uneven stones, her long legs stockinged in brightest blue. Her shock of wild brown hair contrasts the precise elegance of her perfectly tailored coat, cinched just so, almost sporty if it weren’t so flourished at its tails, so sophisticated in every stitch. Both blackly lipsticked with blank and eager eyes, widowed and almost past mourning, each lady still ripens and moistens at the sight of younger beaus. Their fortunes secure enough to freely lust and gift pleasures and presents on a dark-haired count, gallant but penniless from his distant country’s violent revolution or the blushing, bright-cheeked blonde boy, a middle-class cousin to one of the great American families on a lark after college with his better-heeled relatives.

Though elegant in every fold and refined in every movement, their eyes reveal little warmth as they scan with razor hunger the swish of skirts and the shimmy of tails, silently seeking their favorite prey.

John James Audubon, Roseate Spoonbill From The Birds of America, 1827-38. Courtesy audubon.org.

45 Roseate Spoonbill

Ciconiiformes Threskiornithidae Ajaia Ajaia

This spoonbill is one funky motherfucker. A dandy in the muddy marsh, from dark labial pink to blushing schoolgirl carnation, that skinny neck hosts a head only some psychedelic jazzbo deity could concoct. Eyes and throat rimmed with a fleshy hue, his tiny head lined and colored like a minty ballsac gives way to one of the biggest, baddest bills in birdland. A yellow-tinged lip flaps out to a periwinkle tip, large and bulbous, an instrument that would make Cyrano and Durante put their schnozzes away in shame. Virgin spinsters spot this beauty with their brass binoculars and flush with the suggestion of its weird, lascivious majesty.

John James Audubon, Californian Partridge From The Birds of America. Courtesy audubon.org.

128 California Quail (California Partridge)

Galliformes Phasianidae Callipepla californicus

Audubon never saw anything of these but a corpse. Palest brown and rusty red under a webbing of black lines with a rich blue chest, these plumed fat-bottomed birds are either too smart or too stupid to stay clear of you. Hunters love to shoot them, though they managed to avoid Audubon’s rifle. After they’ve been shot and snipped, their skin and feathers come off in one clean tug.

Though I’ve seen a mama toddle along with a clutch of chicks following behind, bumpy and unsure, slowing down and dawdling but always in a row, an overfed bishop with an unsure flock, a pear-shaped chorus-girl in a New Year’s Eve musical. Their tiny feet leave a funny score across the silty dust. California Quail is somehow the state bird.

I love the quail, here only a painted screen to project a fantasy of another place, but outsiders always dream their dreams against the open possibilities of California.

John James Audubon, Esquimaux Curlew From The Birds of America, 1827-38. Courtesy audubon.org.

157 Eskimo Curlew (Esquimaux Curlew)

Charadriiformes Scolopacidae Numenius borealis

This is the only picture by Audubon of a dead bird not being eaten. The male examines his mate’s body, probably displayed by Audubon in this bizarre tragedy mostly to show off her interior feathers.

Of the 497 species included in the final edition of Birds of America, at least seven are extinct: the Carolina Parakeet, Passenger Pigeon, Labrador Duck, Great Auk, Pinnated Grouse, Bachman’s Warbler, and the Esquimaux Curlew. Some of these were, like the Passenger Pigeon, numbered in the billions before humans disappeared every last one.

John James Audubon, Little Sandpiper From The Birds of America, 1827-38. Courtesy audubon.org.

185 Least Sandpiper (Little Sandpiper)

Charadriiformes Scolopacidae Calidris minutella

"No sooner had the little creatures felt assured that I had discovered their treasure, than they manifested a great increase of sorrow, flew from the top of one crag to another in quick succession, and emitted notes resembling the syllables peep, peet, which were by no means agreeable to my feelings, for I was truly sorry to rob them of their eggs, although impelled to do so by the love of science, which affords a convenient excuse for even worse acts." <br/k>—John James Audubon

John James Audubon, Barred Owl From The Birds of America, 1827-38. Courtesy audubon.org.

239 Barred Owl

Strigiformes Strigadae Strix Varia

"The Barred Owl was very often exposed for sale in the New Orleans market; the Creoles make Gumbo of it, and pronounce the flesh palatable..."

—John James Audubon

The bastard son of a French planter, Audubon was born in Haiti in 1785 and reared in France but after settling in New Orleans in 1821 he claimed his birth to be in Louisiana to hide the shadow of his parentage. The Times-Picayune reports: “According to his journal, on Jan 7, 1821, he arrived in New Orleans, where he saw a parade and had his pocketbook stolen while visiting the market. As he forlornly wrote, Audubon found himself ‘nearly again without a cent, in a bustling city where no one cares a fig for a man in my situation.’” He came back and forth but left his home in Louisiana after nine years. Despite this short sojourn in the Crescent City, his name adorns more than a few institutions, though it is conjectured that over a quarter of the pictures were begun in New Orleans and the marsh birds of southern Louisiana are very well represented.

Here, however, a squirrel looks rather nonchalant as the Barred Owl aims a screeching beak at his furry head.

John James Audubon, American Swift From The Birds of America, 1827-38. Courtesy audubon.org.

248 Chimney Swift (American Swift)

Apodiformes Apodidae Chaetura Pelagica

I care nothing for this bird but for the strange cruel curve of its mouth, a rictus, a spooky smirk. Its thin beak with a lick of the artist’s brush is almost evil.

Audubon, the self-appointed man of science, did not attribute to them the qualities of darkness or light but still broke into their nest, a large hollow tree, and murdered over a hundred out of curiosity.

John James Audubon, American Crow From The Birds of America, 1827-38. Courtesy audubon.org.

287 American Crow

Passeriformes Corvidae Corvus brachyrhynchos

I love and hate crows.

My mother, when I was five, splayed out on the couch watching some dark cartoon, wove a tale about her grandmother spotting a crow following her train a century ago and when she arrived, her sister was dead.

Most people distrust a crow, folklore makes them bringers of bad tidings and notorious thieves. They are smart birds and everywhere in America, if I listen now I can hear their caws on the wind. I know they only wait, patient, shrewdly watching to see if I’ll attack or when and where I’ll fall as to pick my bones clean. It’s hard to get comfortable around an animal that would eat you as soon as it could. But with protein scarce, it would be smart to do so.

Crows survive.

So many other birds disappeared under human influenced, homes destroyed or outright murdered into extinction, but crows, hunted merely as pests with prices on their heads, still endure. Unlike other birds, they thrive around humans, happy to peck at garbage and, when given the opportunity, our bones. Hanging around on power lines and peeked roofs, the omnivorous crows wait always for an easy meal.

This one here skulks in a walnut tree, looking back at Audubon with cautious distrust, as he should.

John James Audubon, Field Sparrow From The Birds of America, 1827-38. Courtesy audubon.org.

421 Field Sparrow

Passeriformes Emberizade Spizella pusilla

The song birds that make up the last quarter of the book are not that interesting. Perhaps because they made up many of the last entries for the harried artist and were just rushed. Often Audubon foregoes the background entirely. Or maybe songbirds are not distinguished for their usually small bodies but for their voices, their warble and click, barks and rhythms, the melodious music that make them so moving.

In some paintings amongst the songbirds, five or six birds get shoved into an awkward cluster of foliage, but here the field sparrow stands alone. At a quick glance, I didn’t see him, but there the sparrow stood, hiding in a clump of foliage.

Though his song long silent, I can still imagine him and his ancestors filling the air. No matter how small their bodies, their music filled a forest that once stretched across a continent.

The sparrow survives too.

He knows how to hide, but his naked voice does not. Fearlessly filling the air, beautiful, unfettered, and free.