Upon a Painted Ocean: Edward Burtynsky’s “Water”

Editor's Note

This review was originally published in January 2014, but we’re revisiting it as part of our thematic series in conjunction with Erin Johnson’s “Of Moving and Being Moved” at Pelican Bomb Gallery X. To further explore ideas central to the exhibition, we’re publishing new reviews, personal essays, interviews, and digital artist projects exploring the many different ways we live with water. We also want to use this opportunity to highlight previously published pieces from our archives, which have documented New Orleans’ ongoing conversations on water.

Edward Burtynsky, Pivot Irrigation #11, High Plains, Texas Panhandle, USA, 2011. C-print. Courtesy the artist; Nicholas Metivier Gallery, Toronto; Howard Greenberg Gallery and Bryce Wolkowitz Gallery, New York.

For a species whose bodies are composed of nearly two-thirds of it, humanity has a remarkably complex relationship to water. Despite our physical and social dependence, humans have difficulty living in a healthy relationship with it. Rather than focus on the solutions water affords, we seemingly prefer the challenges it raises, attempting to train, tame, and harness it to our uses and desires.

This complex relationship—as though between maligned lovers—is the subject of an expansive series of photographs by Edward Burtynsky, the Canadian photographer best known for his vibrant, large-scale aerial photographs shot around the world. Global in scope, the series is, in fact, simultaneously being displayed in cities in America, Canada, England, and Germany. On view at three separate locations in New Orleans—the New Orleans Museum of Art, the Contemporary Arts Center, and (more briefly) Arthur Roger Gallery—“Water” is a sprawling, absorbing, worrying, and ultimately exhilarating exhibition that speaks both to our devotion and suffering in regards to this remarkable substance.

Undoubtedly the heart of the exhibition is in the landscapes themselves, the myriad and spectacular places that Burtynsky has explored to capture glimpses of the element in concert with people, landforms, and in some cases, itself. He finds his subject in rivers, lakes, oceans, and deltaic plains, as well as in industrial settings such as canals, dams, locks, and wells, but also in pristine sites such as glacier peaks where humans have never set foot.

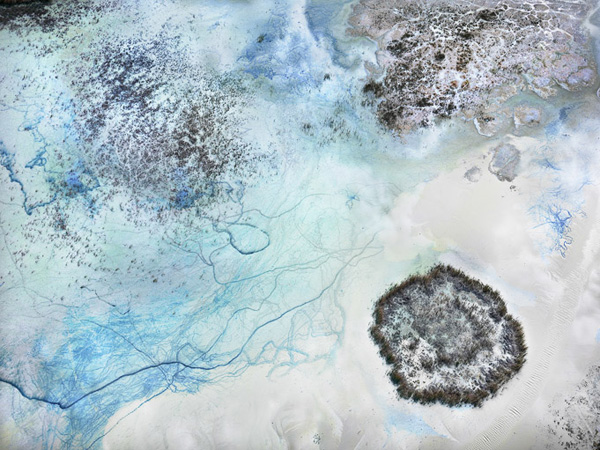

Identifying sites of particular hydrological significance is one thing, but it is the way that Burtynsky transforms these landscapes that sets his work apart from mere cataloguing or documentation (no matter how beautifully or systematically done). Burtynsky’s abstractions—the images of dryland farming from Aragon, Spain, for example—are frequently likened to one of his admitted influences, painter Jean Dubuffet, with these abstractions relying equally on patterning and on visual metaphor. In Burtynsky’s world, rivers take on the aspect of tree branches with limbs and leaves, or neurons with axons and dendrites. Pivot irrigation farms in the Texas panhandle become radar screens, complete with the roving circular sweep of the signal line. Glacial fluvial channels in Iceland become a cloth of woven threads, a lattice that looks as soft and pliable as a woolen blanket. And in terraced rice farms in China, the terraces on the mountainsides do not just resemble the contour lines of a topographical map; they become one.

Edward Burtynsky, Oil Spill #5, Q4000 Drilling Platform, June 24, 2010, 2010. C-print. Courtesy the artist; Nicholas Metivier Gallery, Toronto; Howard Greenberg Gallery and Bryce Wolkowitz Gallery, New York.

These effects are rendered even more dramatically through coloring. Consider his series of the Deepwater Horizon oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico, a disaster with which we have lived since its outbreak almost four years ago. In Oil Spill #5, Q4000 Drilling Platform, June 24, 2010, he captures the emergency vessel assigned to plug the leak in the Macondo well. Though they are undoubtedly bobbing on the open ocean, the vessels appear static, with the water beneath them textured as if it were blackened, volcanic soil. Against this backdrop the colors leap off the print: the vivid orange flare of the well flame, the fire-engine reds of the emergency vessels, and the curtain of rainbow the arcs of water cast, a rainbow that appears almost as a miniature aurora against the night sky.

Edward Burtynsky, Phosphor Tailings Pond #2, Polk County, Florida, USA, 2012. C-print. Courtesy the artist; Nicholas Metivier Gallery, Toronto; Howard Greenberg Gallery and Bryce Wolkowitz Gallery, New York.

Burtynsky’s palette veers from joyful to sobering, but he is best when he is numinous. Phosphor Tailings Pond #2, Polk County, Florida, USA, 2012, is a study in ethereal blues and whites, a depiction of a ghost-world underneath the ice that recalls Werner Herzog’s Antarctic explorations in Encounters at the End of the World. And his series of the Colorado River Delta, where the surface of the water attains a purity of color—teal, aquamarine, even silver—that transcends the surrounding landscape, the filaments of the river searching out the soil in mysterious arterial lines like blood returning to a muscle that has long lain dormant. In Colorado River Delta #3, Near San Felipe, Baja, Mexico, 2011, the crescendo of dawn on the ridges of the riverbanks, fringes of saffron and crimson in an otherwise frozen palette, warm the composition masterfully.

We live in a world of exquisite strangeness and beauty, and Burtynsky aims both to reveal those twin elements and to celebrate them. Time spent with his photographs is best accounted for in what E.M. Forster, in A Room with a View, once called “the hour of unreality—the hour, that is, when unfamiliar things are real.” The political reality in Burtynsky’s images is nevertheless stark. Water is a basic need; it is an entity to which access is often a luxury, enjoyment is an unequal privilege, and use remains legislated, marketized, and contested. Countries either ration its use internally (Israel, for instance, controls the coastal Gazan aquifer, on which 1.5 million Palestinians depend for drinking water), lock it up in fortresses such as the Xiluodu Dam (which Burtynsky depicts), or antagonize one another by virtue of being upstream or downstream of major sources. Cooperation is rarely, if ever, guaranteed, and lost bodies of water such as Lake Chad or the Aral Sea where rusting tankers litter the seabed attest to mismanagement in every corner of the globe.

Edward Burtynsky, VeronaWalk, Naples, Florida, USA, 2012. C-print. Courtesy the artist; Nicholas Metivier Gallery, Toronto; Howard Greenberg Gallery and Bryce Wolkowitz Gallery, New York.

Images such as Manikarnika Ghat, Varanasi, India, 2013, Benidorm #2, Spain, 2010, and VeronaWalk, Naples, Florida, USA, 2012, amply demonstrate these contrasts. In the first, residents of a developing nation cluster around the main water source in their community, using it for a variety of purposes, from transport to harvesting to washing. In the second, water becomes the economic engine for a coastal resort, whose tower blocks clog the print into a faux SimCity-like tableau; here water is open to the public, but is seemingly best enjoyed by the moneyed. In the third, closest to home, a private community in Florida showcases the garish extent to which water is not just a luxury, it is a sign of prestige. As if living within inches of this man-made inlet were not enough, each of the hundreds of homes in the archipelago is outfitted with its own private pool. Presumably the “artificial” water in the pools is safe, whereas the “natural” water in the inlet is not. How privileged these homeowners are, Burtynsky observes, to have the choice.

In so doing, he is asking us to consider the fact that the future of water is in our hands: that our decisions, our attitudes, and our approaches to water will determine the course not just of its future on this planet but of our own. If water is a status symbol now, it will soon become only a survival symbol. For a city which exists beneath sea level, at the end of a deltaic plain on the edge of a coast—as those who live in New Orleans know all too well—we would be well-advised to sit up and pay attention.

Editor's Note

“Water” is on view through January 19, 2014 at the New Orleans Museum of Art (1 Collins C. Diboll Circle) and the Contemporary Arts Center (900 Camp Street) in New Orleans, as part of the NOMA—>CAC initiative.