Through A Lens Darkly, Then and Now

J.B. Borders discusses his experience with Deborah Willis’ 2000 exhibition “Reflections in Black” in relation to a recent documentary by Thomas Allen Harris.

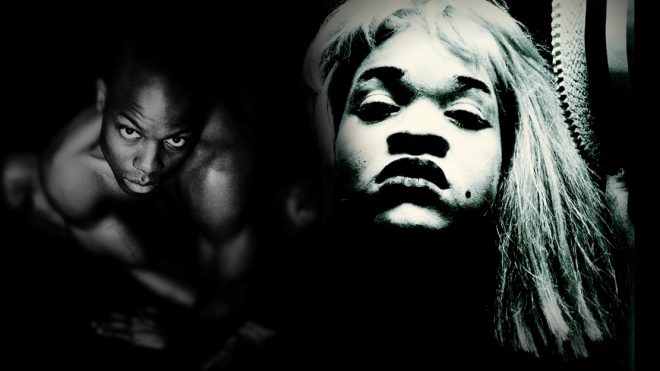

Through a Lens Darkly Film Poster featuring Untitled (Mother), 1998, by Lyle Ashton Harris and Thomas Allen Harris.

I just happened to see Deborah Willis’ brilliant exhibition “Reflections in Black: A History of Black Photographers, 1840 to the Present” one afternoon in Washington, DC, in the spring of 2000. I can’t recall having heard anything about the show before stumbling upon it at the Smithsonian’s Arts and Industries Building. I’m almost certain I was on my way to the African Art Museum—one of my ritual stops back then when I visited the nation’s capital. But I saw a sign for “Reflections in Black” and decided on the spur of the moment to drop in and check it out.

I’ve never been more than moderately interested in or knowledgeable about the history of photography, but I grew up with Ebony, Jet, Life and Look magazines always around homes, barbershops, doctors’ offices, libraries, and other places. Because my young life was saturated in arresting and highly informative images, I suppose I took them for granted, even the work of artist-documentarians like Gordon Parks and the photojournalists who captured the Civil Rights Movement.

Fortunately, by the time I came across “Reflections in Black,” I knew a little about some early black image makers like Jules Lion, a free man of color who mounted an exhibition of daguerreotypes in New Orleans back in 1840. And I had seen the work of another early New Orleans photographer, Arthur Bedou, who was noted for his pictures of Booker T. Washington. I was privileged in the 1980s to become acquainted with the work of other pioneering black photographers like P.H. Polk of Tuskegee and Addison Scurlock of Washington, DC. And like many people of my generation, I was introduced to the work of James VanDerZee in 1969 when the “Harlem on my Mind: 1900-1968” exhibition made a big splash after opening at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art. His photo of a stylish couple wearing raccoon-skin overcoats astride a shiny Cadillac is now an iconic image of Harlem Renaissance/New Negro panache.

Nevertheless, I was completely unprepared for the richness, diversity, quantity, and quality of the work presented in “Reflections in Black.” Wall after wall of knockout shots, some loud and in your face, others more demure and potent. To call “Reflections in Black” monumental would be an understatement, to dub it magisterial would be damning it with faint praise. I walked around immersed in and mesmerized by not only its historicity but also its contemporaneity.

The first time through, I tried to follow the presentation chronologically, but I kept bouncing forward and then circling back. I skipped ahead to the mid- and late-20th century to see if other New Orleans photographers were in the mix. Marion Porter, Keith Calhoun, and Chandra McCormick were there. It was affirming to know we hadn’t been messed over. I could then go back and look more leisurely at the photographs of other home folk like Villard Paddio and Florestine Perrault Collins and learn of countless others I had never heard of—from the amazing J.P. Ball, who worked in Montana in the late 1880s and 1890s, to the digital imagery of Stephen Marc. I could see how appropriately the work of cutting-edge contemporary image workers such as Clarissa Sligh, Lynn Marshall-Linnemeier, Amalia Amaki, Pat Ward Williams, and Albert Chong had been woven into this comprehensive survey.

Production still from Through a Lens Darkly featuring Yo Mama's Pieta, 1996, by Renee Cox.

Suffice it to say I never made it to the African Art Museum that day. Instead, I stayed in the Smithsonian Castle until closing time, bought a copy of the exhibition’s massive catalogue, taxied to my hotel to pick up my suitcase, headed to the airport, boarded my flight, and pored over the book all the way back home.

I’ve been fortunate to hold on to the “Reflections in Black” catalogue I bought that day. It survived Katrina and all the muck and mold that wiped out most of my other possessions. I still pull it off the shelf from time to time to peer at an image or two. And even when I don’t start out looking for them, I frequently flip through the pages and come upon a group of stunning, phantasmagorical images in the last section entitled Alchemy Series, made in 1998 by young photographers who billed themselves as the Harris Brothers—Lyle Ashton Harris and his younger sibling Thomas.

Like most people who have encountered “Reflections in Black,” filmmaker Thomas Allen Harris was awed by curator Deborah Willis’ prodigious achievement in researching, selecting, and presenting nearly 600 images, including 100 that had never been seen before, made by dozens of photographers over a period of 160 years. So 10 years ago, with Willis’ encouragement, Harris decided to produce and direct a documentary film inspired by the exhibition, presumably to reach, teach, and engage more people beyond those of us lucky enough to have seen the exhibition in person. Harris’ objective, he said, was to create “an homage to an enduring legacy of self-affirmation and self-invention” that African-American people and their photographers have confected despite generations of oppression.

The result is a riveting 90-minute documentary, Through A Lens Darkly: Black Photographers and the Emergence of a People. Released earlier this year, it has racked up awards at festivals across the United States, Europe, and Africa. I saw a screening during the New Orleans Film Festival and plan to see it again when it comes back to town the first week of November.

The documentary’s title evokes a New Testament letter sent by the Apostle Paul to early Christians in the town of Corinth: “For now we see through a glass, darkly; but then face to face: now I know in part; but then shall I know even as also I am known.” Ancient Corinth was a place that produced mirrors, which were made of polished metals, usually brass, reflecting images indistinctly, darkly. While Through A Lens Darkly plays upon this verse, the work it showcases shines a ray of light through the “recesses of American history to discover images that have been suppressed, forgotten, and lost,” as its own promotional copy explains, offering clarity on “the role of photography in shaping the identity, aspirations, and social emergence of African Americans.”

Harris devotes some time to contextualizing the black image in America, recalling the long, multifaceted, and voluminous campaign to produce negative images of African Americans—images that depicted us as savage, ugly, dumb, and lazy. He also covers some of the gruesome material shown in the 2000 exhibition and book “Without Sanctuary: Lynching Photography in America,” when white Americans documented and made public spectacle of the beating, genital mutilation, hanging, and burning of black boys, men, and women from the late 1860s to the 1950s.

Production Still from Through a Lens Darkly of works by Michael Chambers and Lyle Ashton Harris. Courtesy Chimpanzee Productions.

Using himself and his own family history as a framing device, Harris then goes on to display a selection of photographs by well-known and less-acknowledged professionals, along with several family photos taken by his grandfather and other family members. They provide an opportunity to discuss deep-rooted issues like parenting, sexuality, passing, and other family secrets. Contemporary photographers like Chester Higgins, Lorna Simpson, Hank Willis Thomas, and others also provide commentary about their work and that of their mentors, including the struggles and sacrifices black photographers made and continue to make in order to carry out their life’s work.

Of course, there are multiple perspectives, visions, strands, and techniques employed by such a wide range of individuals operating over a broad geographic area across several generations and technological eras. Nevertheless, it appears that most of the work can be roughly divided into two piles. On one hand, there is work guided by the observation from 16th-century English philosopher/scientist Francis Bacon that “the contemplation of things as they are, without error or confusion, without substitute or imposture, is in itself a nobler thing than a whole harvest of invention.” White documentary photographer Dorothea Lange most notably used Bacon’s words as her compass. That same principle informs the work of many African-American documentarians like Roy DeCarava and Robert McNeill.

On the other hand, there is a school of black photography that roots itself in what Deborah Willis explained about James VanDerZee’s studio. It was “a theater of desire, ” as she called it, a place in which the photographer and/or his subjects projected images of themselves being all they could be, the pride of Harlem, the best of humanity—even when appearing as their most natural, unassuming selves, as in Carrie Mae Weems’ Kitchen Table Series. These polarities of reality and imagination undergird all the images in Through A Lens Darkly and its predecessor, “Reflections in Black.” That’s largely what makes them both such provocative assemblages, the tensions between the two points of emphasis and the sublime results that occur when these two ideals merge in a single photo.

There is an old saying that others see us based on what we have done but we see ourselves based on what we think we can do. Harris’ project pushes us to contemplate this matter in the lives of others and in ourselves. But it goes a step further: the documentary has produced an online portal called 1world1family.me onto which anyone can upload their own family photos and contribute to an archive of images “celebrating shared values.” There are now millions of photos in the archive and Harris hopes to include millions more.

Maybe this simple act of sharing pictures of ourselves and our loved ones is therapeutic enough to make us all a little more accepting of each other, our beauty, and our foibles.

Maybe not. But it’s worth hoping.

Sundance Trailer for Through A Lens Darkly: Black Photographers and the Emergence of a People directed by Thomas Allen Harris.

Editor's Note

Through A Lens Darkly will screen at 7:30pm every evening from November 2 to November 6 at Zeitgeist Multicultural Arts Center (1618 Oretha Castle Boulevard) in New Orleans.