30 Americans in New Orleans: J.B. Borders

The next response in our series “30 Americans in New Orleans” comes from J.B. Borders, who reflects on institutional history and the ghosts of exhibitions past.

Nina Chanel Abney, Class of 2007, 2007. Diptych, acrylic on canvas. Courtesy the artist and the Rubell Family Collection, Miami.

A couple of years ago when I posted the Corcoran Gallery of Art’s video about the “30 Americans” traveling exhibition on my Better Blackness blog, I had little inclination that the show would ever make it to New Orleans, much less to the city’s Contemporary Arts Center. It isn’t the kind of show the CAC is known for mounting or hosting. In fact, back in the 1980s, artist/curator Richard Thomas had to fight like a pitbull to have his two “Exposition in Black” shows featuring the work of Afro-Louisiana artists installed at the CAC.

The Crescent City Arts District anchor has obviously progressed since then but it hasn’t been as committed to exhibitions of black art as the New Orleans Museum of Art, for instance, which lately seems to schedule a black show annually to be on view during the summertime Essence Festival. The current offering is “Rising Up: Hale Woodruff’s Murals at Talladega College,” which highlights six vibrant racial-uplift narrative paintings from the Negro Art Movement era. A decade ago, NOMA presented “Something All Our Own,” former professional basketball player Grant Hill’s impressive collection of African-American art. Since, it has presented major retrospectives of the work of John T. Scott, our late homeboy, as well as Thornton Dial, Gordon Parks, and a selection of work from the Amistad Research Center’s collection, among other notable exhibitions. So NOMA would have seemed the logical choice to host “30 Americans” in New Orleans. But the CAC snatched the opportunity instead—and merits big ups for doing so.

“30 Americans” is unfailingly enriching, provocative, and stunning even in a couple of cases. More than anything, however, I found the exhibition to be spectral. There are ghosts and echoes and resonances suffusing the entire agglomeration of works.

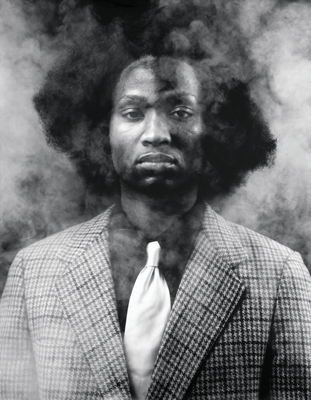

Rashid Johnson, The New Negro Escapist Social and Athletic Club (Thurgood), 2008. Lambda print. Courtesy the artist and the Rubell Family Collection, Miami.

I won’t bother rehashing the discourse about how the post-black concession instantiated in the exhibition’s title is undercut by the substance of its content (“amplified blackness,” one observer called it) or the popular appeal of the show’s primary marketing image, the face of a young black man (which used to be considered taboo for attracting white audiences until gangsta rap started deploying snarling mugs to generate million-unit sales to a 70 percent white clientele). And I won’t mention again how emotionally ensnaring the CAC’s installation is—moving from lightly-charged works on the first floor to progressively more weighty pieces on the second and third stories. Nor will I expound on the multitude of interesting cross-cultural appropriations in the exhibition—from Kehinde Wiley’s ghetto-fabulous remix of Euro-royalty portraits and Jesus-in-the-tomb paintings to Iona Rozeal Brown’s Nipponized settings. And this time, but only this time, I won’t bemoan the lack of any direct NON (New Orleans Negritude) pieces in the pile—after all, no one show can be all things to all people.

But the ghosts of exhibitions past are everywhere you turn. For me, it’s hard to walk into the CAC lobby and see Leonardo Drew’s gigantic cotton bale and not recall Glenn Ligon’s text-wrapped cotton bale in the Malcolm X traveling exhibition that Kellie Jones curated in the mid-1990s. It’s also impossible to come across Mark Bradford’s Whore in the Church House on the second floor and not remember Julie Mehretu’s abstracted satellite-seeming views of urban gridscapes in the same space during Prospect.1. And having recently seen Hale Woodruff’s murals, it’s hard not to wonder what happened to that old-time unabashed positivism when encountering some of the irony, cynicism, equivocation, and self-loathing-masked-as-nuanced-or-honest-interrogation in works like Nina Chanel Abney’s mordant Class of 2007 and Kara Walker’s raunchy silhouettes. (Her A Subtlety on display at the defunct Domino Sugar factory in New York strikes me as a work that should be exhibited ass-forward, not face-forward. The bunda bozales—that wild black behind—is far more potent than the handkerchief head and the juicy lips. But that’s a discussion for another day.)

It’s also hard not to feel the presence of the path-breaking “Tradition and Conflict: Images of a Turbulent Decade 1963-1973” mounted at the Studio Museum in Harlem in 1985 by Mary Schmidt Campbell. That exhibition assembled work from over 50 artists who were responding creatively to the Civil Rights and Black Power movements. While David Hammons seems to be the only artist from that show to be included in “30 Americans,” many of the pieces from “Tradition and Conflict” would be right at home in the Rubell Family Collection. Interestingly enough, most of the pieces in the earlier exhibition were lent by the artists themselves, a complete reversal of the situation for “30 Americans.” It’s also worth noting that none of those “Tradition and Conflict” artists seemed to mind being called straight-up “black” or being described as “militant” or (today’s term) “trenchant” for fear that it might hurt their market value or employability. Yep, it was a different time.

Jean-Michel Basquiat, Untitled (Self-portrait), 1982-1983. Oil on wood. Courtesy the artist and the Rubell Family Collection, Miami.

Those are minor observations, however, compared to confronting the elephant in the galleries (and likely the motive force for the entire exhibition)—Jean-Michel Basquiat (1960-1988), the $50 million (dead) man and the first black artist to break into the upper echelons of the visual arts industry. When “30 Americans” was being organized by the Rubell family in 2007, the highest sales price for a Basquiat was just over $26 million. Last year, one of his works fetched $48.8 million at auction, placing it in the top 25 for prices of single works. Any dunce can see the implications for collectors of similar artists.

So it’s no coincidence, I presume, that Rashid Johnson’s The New Negro Escapist Social and Athletic Club (Thurgood), which evokes James Van Der Zee’s 1982 photographic portraits of Basquiat, ended up as the public face of “30 Americans.” Maybe there is indeed a new Jean-Michel lurking in this collection—along with some super-Basquiats or even a half-Basq or two. There are certainly many worthy candidates in this panoramic mix, some of whom are already bona fide stars and major award winners. Let’s also hope they get paid some Basquiat-type dough before they die, not after. The spirits will be watching, waiting, and judging.

Editor's Note

J.B. Borders is a consultant specializing in nonprofit capacity building. He is a native of New Orleans.

“30 Americans” on view through June 15 at the Contemporary Arts Center (900 Camp Street) in New Orleans.