30 Americans in New Orleans: Howard Conyers, Deborah Anderson, and Jaime Wright

Kehinde Wiley, Equestrian Portrait of the Count Duke Olivares, 2005. Oil on canvas. Courtesy the artist and the Rubell Family Collection, Miami.

Editor's Note

We kicked off our "30 Americans in New Orleans" series last week with an introduction by Pelican Bomb Founding Editor Cameron Shaw. The series seeks to provide a platform for a spectrum of local black voices to respond to "30 Americans," an exhibition of work by black artists currently on view at the Contemporary Arts Center in New Orleans. It continues with the co-founders of iSTEMNOLA—Howard Conyers, Deborah Anderson, and Jaime Wright. iSTEMNOLA is a nonprofit that works to spark and increase the interest of female students and students of color in science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) careers by bringing STEM professionals into the classroom.

The instructions to participants in our "30 Americans in New Orleans" series were intentionally simple: see the show "30 Americans" and tell us what you think. The team at iSTEMNOLA all focused on individual works with an eye to personal and social histories.

Howard Conyers: Being raised in Manning, South Carolina, seeing Leonardo Drew’s stacks of cotton bales made me reflect on the stories my parents shared with me growing up. They both came from families who were sharecroppers. I take for granted things a lot of people may not have seen or heard—my wife, who is from Milwaukee, said that she had never seen cotton bales up close in real life. It made me think about the challenges that blacks in the South have had to endure, but they always had a very strong sense of community. That sense of community is waning, even though we desperately want to think that we have arrived in some sort of a way, like the man on the horse in Kehinde Wiley’s portrait. Unfortunately, we still have a long ways to go.

Throughout the exhibition, this struggle—what progress really looks like—was illuminated. Standing in front of Hank Willis Thomas’ photograph of the basketball player chained and held down by his ball, I thought about the book Forty Million Dollar Slaves and the number of professional athletes who, unlike the team owners, go bankrupt after their playing days. So many black kids still believe that being a basketball player or professional athlete equals success and they miss the other abounding opportunities. It reiterates how important it is to educate our kids to see their future beyond athletics, like in my case in science, technology, engineering, and math.

Leonardo Drew, Untitled #25, 1992. Cotton and wax. Courtesy the artist and the Rubell Family Collection, Miami.

Deborah Anderson: Have you ever read something that you knew was deep but didn’t understand what the heck it meant? That’s how I felt when I saw Untitled by Glenn Ligon. When I read “I Sell the Shadow to Sustain the Substance” spelled out in blackened neon lights, I just knew it had to mean something powerful. And it does. It’s a quote from Sojourner Truth about how she would sell photos of herself to fund the travel to her anti-slavery speaking engagements in the 1860s. Selling vanity for a purpose.

There are a few works by Ligon in “30 Americans.” The other piece that stood out to me was Condition Report D, which puts two posters side by side, like those used in the 1968 Memphis Sanitation Strike and later during the Million Man March. The first poster is just the words, “I AM A MAN!” The second poster is covered in writing pointing out where there are marks, blemishes, and stains on the background. It is as if the first poster represents how a lot of people want to see a man and the second poster points out all of his imperfections. Both men and women often think that if you’re a man you have to be without fault and not make apparent your weaknesses and downfalls. I really saw it as a statement of strength. When I thought about the poster’s use during the Freedom Movement, the writing became all the insults and nasty things that were said about black men at that time—black men are lazy, they are stupid, they are weak-minded. This was the purpose and power of raising these signs at different marches nearly 30 years apart and I still felt it in the gallery. It was as if to say: Despite what you say about me, I AM A MAN!

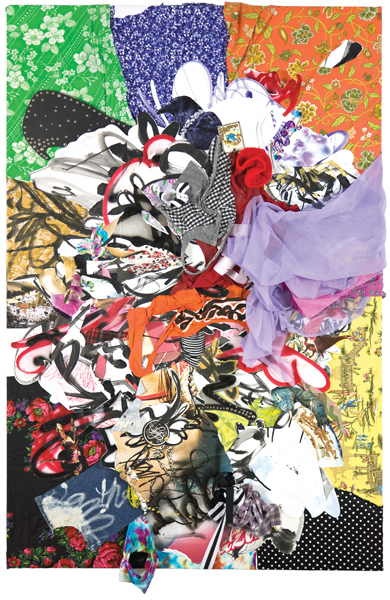

Jaime Wright: As I viewed the work of Shinique Smith, I could see fabrics that I relate to my childhood. The orange, blue, and green floral prints remind me of my grandma and the patterned gown she wore around the house when I was a little kid. I can see her preparing a meal in the kitchen with this gown on. My little sister's Easter dress would have had the light purple fabric on it. Our family would go shopping for my little sister’s Easter dresses together. And the purple fabric would have been a part of it.

Shinique Smith, Managerie, 2007. Mixed media on canvas. Courtesy the artist and the Rubell Family Collection, Miami.

Editor's Note

Howard Conyers is an engineer at NASA. Originally from Manning, South Carolina, he has lived in New Orleans since 2011.

Deborah Anderson is Associate Producer at TurboSquid, a 3D model marketplace. Originally from Detroit, Michigan, she has lived in New Orleans since 2008 with a two-year break in South Korea.

Jaime Wright is a Construction Manager at the US Army Corps of Engineers. Originally from Miami, Florida, he has lived in New Orleans since 2008.

“30 Americans” on view through June 15 at the Contemporary Arts Center (900 Camp Street) in New Orleans.