Survival Guide: David Sullivan

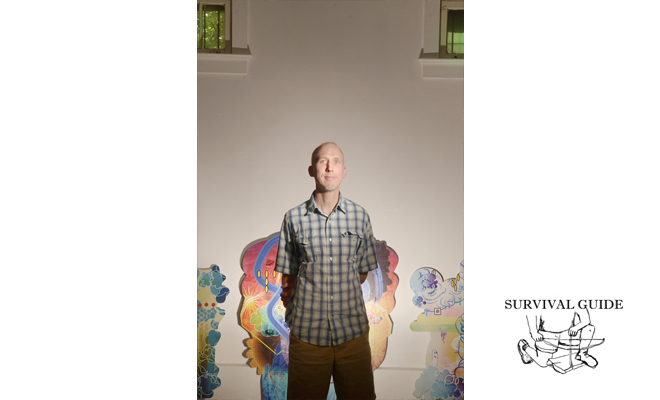

Artist David Sullivan has lived and worked in New Orleans for over 20 years. Aubrey Edwards photographs Sullivan in his home in the Irish Channel, which doubles as his studio.

Survival Tip: "Back your work up multiple times, multiple places."

Editor's Note

In the sixth and final interview in the “Survival Guide” series, Raina Benoit talks with artist David Sullivan. At the intersection of abstract painting and video game imagery, Sullivan uses digital media and animation to address sociopolitical and environmental concerns, creating nightmarish worlds that uncomfortably mirror our own.

Raina Benoit: Many of us are choosing to have children later in life, myself included. How has becoming a father almost three years ago affected your work?

David Sullivan: In many ways having a child was an ethical dilemma for Courtney and me. [Sullivan’s wife is the artist Courtney Egan.] We were ambivalent about bringing life into a situation that we think is untenable. Our society can’t continue to consume the way it has with the limited resources we have on the planet. Unless we get our act together quickly, there will be significant hardships in the future. I want the world that my son is going to be living in to be as sustainable and enjoyable as possible. It has made the issues that my artwork explores—the intertwined relationship between the petrochemical industry, the communities along the Gulf Coast, and our consumer society—even more pressing.

Thinking on a micro level, I attended a residency in Utah called Spiro Arts. It was a test to see if it’s possible for me to raise a kid and do some work. This residency is one of the few that accommodates spouses and children. When my son was an infant he came with me for three weeks and it is possible to do work with a child. It’s just difficult. It’s different now because he’s a toddler. When he was a baby he could only crawl so fast and was easy to keep up with. In a couple of years an artist residency might be possible again.

RB: We are all shaped somewhat by our parents’ professions, whether they are professors, plumbers, or psychologists. I wonder what influence visual artists have as parents on the way their children see the world. In my family, we look at so many things from visiting galleries and museums to walking around our neighborhood and thinking critically about the systems of organization around us. It’s interesting to think about what children are absorbing while being backpacked around by mom or dad.

DS: I hesitate to say that we are raising our child in any special way. Courtney and my personal priorities are certainly on the creative act—experimenting, experiencing, and refining something that is hopefully revelatory for others. Due to our studio practices, our son definitely has to grow up with a lot more crap around his home than most children. I think of my dad who was a physics teacher. He was always encouraging us to look at the world around us by questioning the nature of how things work. I think that artists are quite similar to scientists in that we are always experimenting with different processes or materials—the experiments might be physical or conceptual. I can only imagine that our son will grow from our belief systems as I’ve grown from those of my parents.

RB: How important is the studio space to the work you create?

DS: Most of my commercial work is freelance animation for broadcast or for film. I was working at an animation job and I got laid off. My severance package came at just the right time and we bought a house in the Irish Channel at a time when that area was relatively cheap. We were able to get a really nice big open space. I’ve enjoyed having light and windows in my studio and I assume it affects my work in the same way. It makes it more enjoyable to do. And it’s all right here. We live in our studio space and can work anytime.

RB: I love walking through an artist’s studio. It’s like walking into that artist’s brain and seeing the inner workings of the mind. Currently the studio that you share with your wife Courtney is filled with a mixture of projects in progress and toys. Can you talk about how your studio practice has changed since the arrival of your son? When do you find time to work?

DS: My output has dramatically decreased! I take care of my son during the day, so most of my work happens during naptime and at night. My time feels more spread out and it’s more difficult to have continuity. It’s a brainteaser in terms of what I’m supposed to be working on and when. For me, programming is not natural. The longer I go without doing it the harder it is to get back into it. As for the animation work, I continually make things harder for myself by trying to learn new things. I’ve been doing two-dimensional prints and paintings for years, so I don’t have to think about how to use the tools. Recently, I’ve been working more with the animation and the interactive projects, so my prints have been on the back burner. In terms of my process, I think I’ve been spending my time finishing projects that I actually started when we were pregnant. I’m living off of my creative freedom pre-fatherhood.

RB: Do you install all of your shows? Has having a child changed your approach to choosing which shows to participate in or what work to exhibit?

DS: Courtney and I are the installation and tech team. We handle any kind of maintenance or troubleshooting that’s required. I can send the animations via the internet, but for my installation and print work the exhibitions have been all in a day’s drive.

RB: Your projects are primarily self-funded. Do you have a system that determines how much you are willing to spend on a show taking into account travel, installation, and production?

DS: Not really. Between Courtney and me, we have to figure out who is showing what and where and how many projectors or monitors we need. It’s only recently become an issue because we are showing a lot more work these days.

RB: You make it sound pretty simple! You have been living in New Orleans for over 20 years. How have the realities of being an artist differed from what you thought it would be?

DS: When I was in grad school there was still this modernist narrative of what an artist should be—alone in the studio, then somehow magically the public finds out about the work, sees it, and appreciates it. Obviously once I left school I found that process didn’t really work. I’m still not very good at pushing things forward on the business end. Writing grants and proposals, networking, and things of that nature are not fun but are an important part of the process.

RB: Do you think that artists have to self-promote, market, and network now more than ever?

DS: I think it may have always been this way, but now there are more people coming out of MFA programs and more people in general. There is so much information out there. We see so many images all the time and so many artists. It’s hard to rise above that.

RB: What then have been some of the benefits or challenges of living and working as a digital and multimedia artist in New Orleans? And what’s kept you here?

DS: That’s a question that Courtney and I have posed often to ourselves as artists working in digital and new media in a city that has not been known for being a progressive art location. I feel New Orleans has embraced our work, but there‘s not a wide base of collectors nor other types of funding for our work that might exist elsewhere. For people working with digital technology, this isn’t really the town. So why are we here? Because we love the city.

David Sullivan, Pump Me Up, 2012. Acrylic and glitter on inkjet print. Courtesy the artist.