Part 2: Will the real Nina Schwanse please stand up?

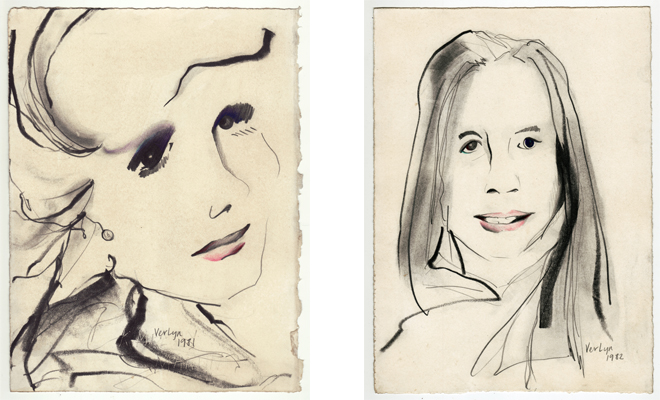

Nina Schwanse, Veronica Compton, Untitled Prison Drawing (Kimberly Martin), 1981 (left) and Veronica Compton, Untitled Prison Drawing (Dolores Cepeda), 1982. Both 2013. Both mixed media on paper. Courtesy the artist.

Editor's Note

In the second of this two-part series, curator and writer Amy Mackie interviews artist Nina Schwanse on the occasion of her exhibition “Hold It Against Me: The Veronica Compton Archive” at Good Children Gallery. The exhibition weaves together fact and fiction in an unconventional archive based on the life of Veronica Compton, who was convicted of attempted murder and incarcerated in 1981 as a result of her relationship with Kenneth Bianchi, aka “The Hillside Strangler.”

Amy Mackie: Why and when did you become interested in Veronica Lynn Compton?

Nina Schwanse: Several years ago, my friend Maureen Johnston, who is from Bellingham, Washington, was talking about how it became a nexus for serial killers. She told me about Veronica Compton and I was immediately fascinated. It was also about place, specifically the Northwest, and the aura of creepiness that exists there—a mythology of murder in the vein of Twin Peaks and River’s Edge. My research was originally focused on this area of the country, but after I heard the story of Veronica, I ultimately narrowed my focus to her experiences.

AM: What is it about Compton’s psychology that appealed to your sensibilities as an artist?

NS: She interested me as someone who went to such extremes for a man. She was under Kenneth Bianchi's spell. I previously did a project about Amy Fisher who also tried to kill a woman while under the spell of a man. I felt that Veronica Compton and Amy Fisher both occupied similar positions as femme fatales, but Veronica was somehow marginalized and more off the grid than other women who have committed or attempted heinous crimes.

AM: Can you talk more about how the idea of a femme fatale fits into the chronology of your work to date?

NS: Well, there was the Amy Fisher project. I made a bunch of paintings of her and I made a video, which was the first video I acted in. I also did a project about JonBenét Ramsey that consists only of paintings. She was a victim and also a sexualized child. It follows that lineage.

AM: Have you ever attempted to contact Veronica Compton?

NS: I have not. While making the work for this exhibition, I wanted to have creative freedom, to be able to fully fictionalize the story without feeling I had any responsibility to the facts, but I do plan to contact her in the future.

AM: Do you know much about her life following her release from prison in 2003?

NS: She married a professor while she was in prison and had a child with him. I assume she is completely rehabilitated. She makes paintings and music, which are very different than the kind of work I made as her for this show.

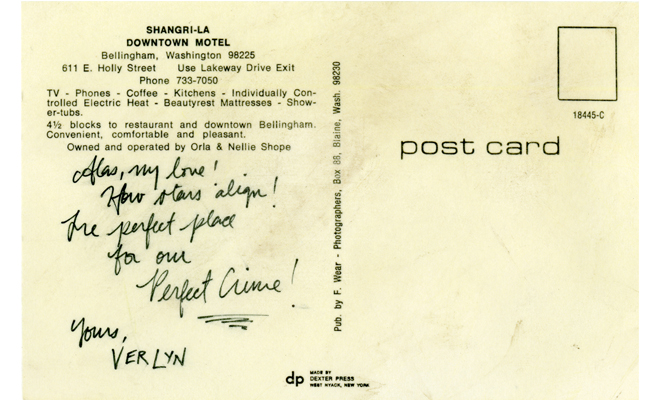

Photographer unknown, The Shangri-la Downtown Motel, Bellingham, Washington, no date. Vintage postcard.

AM: In the exhibition, you have paintings, drawings, photographs, a video, and text-based works (a fictionalized version of the play, The Mutilated Cutter, and also letters to and from Kenneth Bianchi and Veronica Compton). How did you determine that these items would best illustrate the story?

NS: I wanted to illustrate different elements of this woman’s psychology over a brief period of time, to tell her story, without being too literal. The letters give a glimpse of her relationship with Kenneth Bianchi without spelling everything out. I didn’t want to have wall text to explain everything. I provide small clues throughout the exhibition. The play does this too. The paintings establish her as a practicing artist and the photographs serve as documentation of the relationship, what she was trying to communicate by sending these images of herself [based on actual photographs that Compton sent to Bianchi in prison].

AM: How did Compton and Bianchi first connect?

NS: Well, Veronica first sent a letter and her play. The photographs were sent later to get his attention.

AM: You’ve said that when you were making the work you were attempting to “channel Veronica Compton.” Did you conjure certain imagery or ideas? How did you attempt to put yourself in that mindset?

NS: I read a book of letters from female prisoners, which says a great deal about why these women committed crimes. It helped me to relate to their experiences, their hardships, and understand what led them to such extremes. I was also listening to a lot of ’60s girl groups and Doo-wop while I was making the work and much of that music is about how desperate a woman is for a man to love her, how they were meant to be together, how she would do anything for him. I was channeling that energy of desperation. The music I listen to while I work has a lot to do with how it develops and helps me embody a certain persona.

AM: One of the most complicated issues about this project is that you cross certain boundaries in terms of authorship and historicity. In creating a fictionalized account of a real person, how do you negotiate those terms? It’s not an E! True Hollywood Story, it’s not a documentary, it’s not intended to be an accurate account of the life of Veronica Compton. As an artist, how do you explore this nebulous place where you take bits of knowledge then fill in the gaps?

NS: I’ve done a lot of work that involves taking on the persona of people who actually exist. Much of my research was based on a True Crime paperback and also Veronica’s letters that were published in a book. Many accounts of Veronica’s story contradict one another and seem to be fictionalized. There doesn’t appear to be one real picture, one true story about her life. There is no definitive Veronica Compton.

AM: But you’re leading the audience on to some degree, no? The press release isn’t exactly true; there are elements of truth, but you’re also blurring the lines. It begs the question, where does Veronica end and Nina begin and vice versa? And where does the curator begin and the creator end?

NS: I do very much take on the role of Veronica and I thought extensively about what it would be like to be her. Veronica was an actress and I could see that perhaps she was playing a role when she first struck up correspondence with Kenneth Bianchi, but that role took over her life. I think I undergo a similar transformation when I begin a project and take on someone else’s persona. It becomes very consuming. It’s an excruciating process, but in the end it can be cathartic.

AM: Two of your recent videos, Baberental.com and Civil Realness: Grant vs. Lee, have received considerable attention, but you were trained as a painter. Can you talk about the leap between making static two-dimensional work and making performative videos?

NS: I’ve always made both paintings and videos. I made videos as a teenager, but then as an undergrad [at The Cooper Union in New York], I mostly made paintings. My father is a filmmaker, so I grew up around commercials, which found its way into my work. At a certain point in college, I considered myself a “conceptual painter,” everything was a “project,” a means to communicate an idea. I soon realized, however, that the paintings couldn’t always communicate these ideas on their own, so I turned to video and performative work even though I don’t have a background in theater or performance.

Nina Schwanse, Postcard (never mailed) found in motel room, September 1980, 2013. Archival inkjet print. Courtesy the artist.

AM: This idea of being a “conceptual painter” and even the history of conceptual work in a larger sense is very interesting in view of this project. You include a number of text-based works. I would argue that the press release is even a work in the show [Schwanse nods in agreement] and the wall labels also play a pivotal role. Language is, in some ways, the most important medium you embrace in this exhibition.

NS: Yes, the wall labels include many clues for the viewer. The year that the works were supposedly made is included in the titles.

AM: What is the future of this project? Do you think it will take on other iterations? Will the archive grow?

NS: There are other works that didn’t make it into this particular exhibition and I’m specifically interested in making a book. I guess the next step is to get in touch with Veronica Compton. I think that would be the ultimate catharsis for this project, to make a book and give her a copy and see what happens.

Going back to this issue of authorship and making and showing paintings and drawings in someone else’s shoes, the idea of being an artist and attempting to make something precious and valuable to the viewer and put your name on it is something that is often a struggle for me. Part of my practice is about removing myself from the equation and going into character. By extracting myself from the experience of art making, it demands more from the viewer, but it’s more rewarding for me as an artist.

AM: In some ways it makes you more and less vulnerable all at once. It removes you, puts you at a distance, but so much of you is very present.

NS: I put so much of myself in my work, but it’s easier for me to think of it as not being “Nina.” But you’re right, I do make myself very vulnerable.

I’ve actually been reading Wayne Koestenbaum’s Humiliation and have realized that my work isn’t necessarily about exploitation or objectification, but about the experience of humiliation. Veronica Compton humiliated herself to Kenneth Bianchi, to the public, to the media. Baberental.com is definitely all about humiliation, taking human experiences and transforming them and finding something transcendent in moments of shame.

Editor's Note

“Hold It Against Me: The Veronica Compton Archive” on view until July 7 at Good Children Gallery.**

In the first interview in this series, Amy Mackie interviews Nina Schwanse in the role of Veronica Compton.